Names of Zeus: Amun

author: Karnonnos

Amon is the God of Gods in the Egyptian pantheon. He was also known, however, as the ultimate mystery: the hidden power of the realm and the entire universe. The corpus of ancient Egyptian civilization contains many texts about him that are vague and difficult to interpret compared to those about Zeus or Jupiter, yet they overwhelmingly emphasize his majesty and primacy.

His priesthood was located in Thebes, one of the most important cities of Egypt. The High Priest of Amon held the highest religious authority in the state and was second in importance only to the Pharaoh himself.

By the time of Pindar, Amon had been given Hellenistic characteristics and became known as Zeus Amon. Alexander the Great formally inaugurated and established this specific cult of Amon among the Egyptian people, who welcomed him as a liberator from Persian rule.

Herodotus illustrates that this was no secret:

Book 2.42, Histories, Herodotus

"The Egyptians call their highest God Amon, whom the Greeks identify with Zeus. For it is their belief that he is the ruler of all and the father of Gods and men."

AMON, RULER OF THE GODS

Amon holds the ultimate and supreme position in the Egyptian pantheon.

Many throughout history have misunderstood the Egyptian pantheon as a form of egalitarian polytheism, where all Gods are considered "equals", a notion contradicted by the texts. Others, on the opposite extreme, have suggested a rigid monotheism centered around Amon. This perspective, championed by scholars such as Emmanuel de Rougé and other Egyptologists since the Victorian era, has influenced modern interpretations. Additionally, certain negative historical events, such as the rule of Akhenaten and other interlopers, have further shaped these perceptions.

High Priest Hooded Cobra explains the significance of this duality, something Egyptian initiates fully understood among themselves. The primary worship of Amon and Atum was the focal point of Egyptian religion, as Amon was the Pharaoh of the Gods. One of his titles in the Coffin Texts, Amon, Lord of Thrones-of-the-Two-Lands, references his division of power.

A key aspect of his divine symbolism is his paternal nature, extending even to other Gods. The Cairo Hymn, for example, asserts Amon's primacy as the Father of the Gods, the Ultimate Father:

Cairo Hymn

"Father of the fathers of all Gods..."

In alignment with his creative attributes, Amon was regarded as the most supernal and highest of all Gods. He is repeatedly described as bringing the world into existence through the tears and sweat of his eye, contrasting with the previous state of blindness and void.

He was equated with the Oneness of the universe and the other mysterious Creator God, Atum, as a consequence of this assertion. The Egyptian hymns to Amon also reference his primacy as ruler over all things:

Boulaq Papyrus (XVIII Dynasty)

The One maker of all things,

Creator and Maker of beings,

From Whose eyes mankind proceeded,

From Whose mouth the Gods were created.

THE HIDDEN GOD

The inscription of Pharaoh Unas reveals much about Amon and his mysterious role. Another title attributed to him is "He whose name is hidden," a phrase frequently found throughout the Coffin Texts.

- CT 132 / II 154: I have sat with my back to Geb, for I am he who will judge in company with Him whose name is hidden...

- CT 147 / II 207: Have judgment with Him whose name is hidden...

- CT 148 / II 220: ...for you have reached the horizon, having passed by the enclosure of Him whose name is hidden.

- CT 148 / II 221: O Falcon, my son Horus, dwell in this land of your father Osiris in this your name of Falcon who is on the enclosure of Him whose name is hidden.

- CT 148 / II 223: See Horus, you Gods, I am Horus, the Falcon, who is on the enclosure of Him whose name is hidden.

- CT 682 / VI 310: He has flown and soared as that Great Falcon which is on the enclosure of Him whose name is hidden, who takes what belongs to those who are yonder to Him who separated the sky from the earth and the Nun.

Unlike other Gods tied to visible phenomena (the sun, sky, Nile, etc.), Amon was inherently transcendent and formless, representing the unseen air or creative wind. Early on, he was even considered a God linked to the air: invisible yet life-sustaining.

KING OF KINGS

Amon’s central role in the Egyptian state was to preside over the Pharaoh and the nation, acting as its patron and divine benefactor in all circumstances. His name was particularly invoked during coronations and the establishment of a new rule, symbolizing his breath of life into the reign of the ruler. Numerous records also highlight his connection to the Pharaoh’s great achievements, as exemplified in the case of Pharaoh Hatshepsut:

Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many – Erik Hornung

Characteristic of such exceptional cases is a text that attributes to Queen [sic] Hatshepsut the quality ntrj "divine-ness."

At the return of the great trading expedition that Hatshepsut sent to the distant African incense land of Punt, her assembled subjects adored and acclaimed the queen "in the instances (zpw) of her divine-ness" and "because of the greatness of the marvel that happened for her" (Urk. IV, 340, 5-6).

This was not an ordinary event or action of the queen but a solemn and exalted moment when her divine nature was made manifest to the entire world. It was the moment when her vow to the King of the Gods, Amon, to transform his terrace temple into an incense land within Egypt, was about to be fulfilled. The queen regnant revealed her divine essence through the sacred aroma and golden radiance emanating from the Gods themselves.

Pharaohs often cited Amon as aiding them in achieving their goals and acting as their savior. The successful maintenance of military campaigns demonstrated his willingness to uphold a relationship with the Guardian of Egypt. An example from one of the inscriptions of Qadesh, attributed to Ramesses II, illustrates how Amon was regarded by the rulers of Egypt:

Pylon of Ramesses II, Luxor

I pray from the ends of the foreign lands,

and my voice resounds in Thebes.

I found Amon had come when I cried out to him.

He gave me his hand, and I rejoiced.

In effect, Amon determined who should be Pharaoh and who should remain one. The Pharaoh’s legitimacy, and thus the fate of Egypt, rested on his divine endorsement.

Pharaohs also celebrated the Heb-Sed festival to renew their royal power. Texts and reliefs from these festivals often depict the ruler’s claim that Amon personally approved of his reign.

PRIESTHOOD OF THEBES

The Theban priesthood was the most important in Egypt, as Thebes (Waset, modern-day Luxor) was the religious center of the realm. The highest and most sacred individuals served among its ranks. A testament to their authority is the fact that the High Priests of Thebes intervened multiple times to take over total governance of the country when it faced severe danger.

Amon was worshipped as the patron of the great city, alongside Mut (the goddess of sorcery) and Khonsu (the god of creation and the Moon). The largest and most grandiose Temple of Amon was located in Karnak, a district of Thebes.

Despite the name, it is not a single temple but a vast complex of temples, chapels, pylons, and obelisks. As if to emphasize the primacy of this God in the entire universe, it remains the largest religious structure ever built, covering an area of over 200 acres (810,000 m²). Awe-inspiring and immense in scale, Karnak became the major religious center of Egypt, alongside Memphis and Abydos. The annual Opet Festival was celebrated here, during which the statue of Amon was paraded to the Waset Temple.

Much of the original planning and design of the temple were carried out by Pharaoh Hatshepsut, who was prolific in constructing monuments for Amon. However, the Hypostyle Hall, a massive structure with 134 towering columns, the largest standing 21 meters (69 feet) high, was ultimately completed by Pharaoh Ramesses II centuries later.

The complex includes multiple sanctuaries dedicated to various Gods, such as the Triad of Khonsu and Mut, but the most important is the Great Temple of Amon. Much of the temple is also dedicated to Amon-Ra, which has been a source of confusion for historians.

Daily temple worship of Amon at Karnak included morning, midday, and evening rituals involving incense, libations, and hymn recitations by priests on behalf of the king. Through these practices, from the grand festivals to daily rites, Amon was venerated as a majestic yet mysterious God, one whose presence could bless the land, affirm kings, care for commoners, and even provide guidance when properly invoked.

In Lower Egypt, the cult of Amon spread rapidly during the New Kingdom. Pharaohs built Temples of Amon in Memphis, at the new capital Pi-Ramesses, and a major sanctuary at Tanis in the Delta. After the heresy of Akhenaten, the cult of Amon expanded even further.

Amon’s worship also extended widely to Nubia. Egyptian rulers built or expanded temples to Amon in Nubian regions, such as Napata/Jebel Barkal, and Amon became the chief God of Nubian kingdoms as well. The Nubian dynasties of Egypt exalted Amon and Atum together. The influence of these two Gods can be profoundly felt throughout Africa.

These temples were not only religious centers but also economic hubs, endowed with vast land holdings and a large workforce.

GOD’S WIFE OF AMON

In addition to male clergy, a unique institution in Amon’s worship was the “God’s Wife of Amun,” a title given to royal women acting as High Priestesses. The practice existed earlier, but Pharaoh Ahmose I (c. 1530 BCE) elevated his wife, Ahmose-Nefertari, to this position, making it one of great prestige and political influence. The priestess would personify Amonet, the female consort of Amon, or Mut, the female member of the Theban Triad.

In later periods (especially the Third Intermediate Period), this office was used to consolidate power. The ruling Pharaoh’s daughter would become God’s Wife of Amun at Thebes, effectively controlling the Amon priesthood and temple estate.

FESTIVALS OF THE CREATOR

Worship of Amon included grand public festivals that were highlights of the religious calendar, especially in Thebes. The most important was the Feast of Opet, an annual festival to rejuvenate pharaonic power. During Opet, the portable barque (boat) shrine of Amon, a gilded boat-shaped shrine carrying Amon’s statue, was carried in procession from Karnak Temple to Luxor Temple.

Amid great ceremony, the image of Amon visited Luxor to unite with the aspect of Amun at Luxor (sometimes linked to Amun-Min for fertility) and ritually reaffirm the king’s divine legitimacy. Opet lasted many days, featuring processions, offerings, oracles, and celebrations involving both priests and the public.

Another major Theban celebration was the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, which honored the dead. In this festival, Amon’s barque, along with those of Mut and Khonsu, was ferried across the Nile from Karnak to the western bank so the God could visit the mortuary temples and necropolis, symbolically uniting with deceased souls.

These festivals allowed ordinary Egyptians to see and worship the typically hidden God, as his images were carried outside the temple, fostering popular devotion.

DEITY OF FATE AND PEOPLE

Amon was associated with fate. This aspect of the Great God portrayed him as one who “listens to the petitions of those calling upon him.” Symbolically, he was regarded as an advocate and patron of the innocent and the downtrodden. Many sought his worship or oracles to transform their circumstances.

Common people turned to Amon with personal appeals, reflecting a growing sense of personal piety. Amon was regarded as a compassionate deity who hears the prayers of the humble. New Kingdom and later hymns call him the “minister of the humble” and “he who comes at the voice of the poor,” portraying him as a champion of the underprivileged who interceded on behalf of ordinary worshippers.

This aspect of Amon as a personal, ethical God suggests a theological broadness in his role beyond the state and Pharaoh, making him accessible to all levels of society.

Ancient texts repeatedly emphasize that Amon ordains all that is, will be, and was. His deputies, such as Seshat, encode these concepts into reality. The title “Lord of Ma’at” is constantly applied to him as the sustainer of all universal circumstances, alongside Atum. References to him as “the ultimate cause” further demonstrate how Egyptians viewed his role in cosmic order.

In line with this belief, the Pharaoh’s mother was often depicted as being visited by Amon prior to pregnancy, reinforcing to the Egyptian people that his rule was predestined.

WIND AND WEATHER GOD

Amon, much like Zeus, represented the winds, storms, and tempestuous weather. His interventions were often marked by storms and tempests. The fragile health of the Nile-dependent civilization was believed to be in the hands of the head of the Gods.

Along with his deputy Shu and other Gods, Amon ruled over the skies and was regarded as an active force in weather patterns.

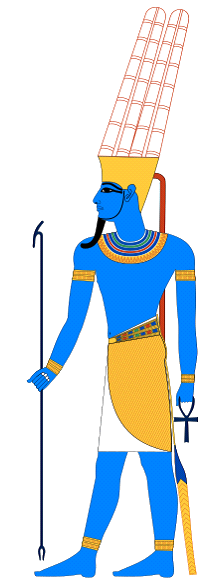

IMAGERY OF AMON

In the majority of representations after the heretical Amarna period, Amon is depicted with blue skin. One meaning of this is to demonstrate the primacy of Amon residing in and ruling over all facets of the cosmos, just as the sky covers the earth. The specific shade of blue, as opposed to other colors such as green or black, which are also sometimes associated with the God, relates to specific spiritual levels, all of which Amon has mastered in totality. Blue as a color is also tied to Zeus, with his globe and mantle, among other things.

Amon typically wears a very tall headdress of two falcon feathers, known as the shuti. The two feathers, alongside the golden tiara, represent traditional kingly power in Egypt and serve to emphasize the fact that he is the King of the Gods, Demons, and Men.

Lying within the symbolism of the crown is another code related to the elements of the universe. The two feathers represent the fully separate elements of fire and water, while the gold tiara represents the earth, magnetizing the two out of the center. The red linen band extending from the back (the sheshed or streamer) represents air, which is connected to the rest yet flows outward independently.

The crown is significantly tall to demonstrate that Amon’s power reaches entirely into the firmament of the aether, beyond the capacity of the other Gods. The symbolism of the dual feathers also signifies that he expresses the internal realm of Satya, the Truth, into active existence.

Amon also holds the was scepter, typically associated with Set. He rules over the inert and spiritually lacking humans as well as the spiritually activated initiates, yet all who undergo initiation and all practitioners of magic must pass through him regardless. The scepter serves as a visual symbol of Dedication to him. Evildoers and those who falsely claim to represent the Gods in malevolent ways are destroyed by its power.

Ram-like imagery has been tied to Amon from a very early stage in Egypt. Sphinxes adorned with the head of a male sheep or a horned human head were crafted to convey significant truths about the God of Gods. Similar to Khnum, Amon’s ram horns symbolize the origins of all life, but in his case, they also represent the unraveling and expansion of existence itself, beyond just biological life.

In this context, the protective and wise stance of the ram over Pharaoh Amenhotep III demonstrates the fierce ability of the God of Gods to protect any God-King under his patronage. His immense size and terrifying force eclipse even the majestic ruler of Egypt. In this representation, the powerful ram exhorts the Pharaoh to act as the dispositor of life and civilization, to maintain the laws, and to always uphold the active defense of the realm. This statue was found in Karnak, a district of Thebes.

One important note is that the name and visual symbolism of Amon have often been misused and, in modern times, confused with Amon Ra, a different God whose name was later included in the Goetia as “Amon”, leading to further confusion. With Amon Ra, these symbols take on distinctive meanings.

Amon also took other forms: a goose (earning the epithet “Great Cackler,” linking him to the primordial cosmic egg), a serpent (symbolizing renewal through shedding its skin), and even an ape or crocodile in certain local interpretations.

These diverse sacred animals and forms emphasize Amon’s all-encompassing nature. Yet, in all his manifestations, Amon remained hidden in essence. For example, at Karnak, his cult image was typically kept veiled and secretive. This invisibility, combined with his creative power, made Amon a God of profound theological significance, representing the unseen divine force behind all existence.

ZEUS AMMONAS

Zeus Amon, also known as Zeus Ammon or Zeus Ammonas, began to appear when Greek states cultivated contact with Egypt. Although often associated with the Greek period of Egypt, this representation is very ancient and appears in the works of Pindar, specifically in reference to the colony of Cyrene:

Pythian Odes 4.16, Pindar:

"And establishing that city by the fountain of Apollo and the fertile land of Zeus Ammon…"

Waset itself was also called “Diospolis”, or the City of Zeus, alongside its more typical name, Thebes.

Typically, this personification of Zeus is adorned with the horns of the ram. He was worshipped primarily in Cyrene, a region of modern-day Libya, which at the time had a population of Greek colonists. The worship of Zeus Amon was directly tied to the aspects of Amon dealing with fate in particular.

Amun’s cult also featured oracles and processional or pilgrim practices. In the New Kingdom, Amon’s oracle was often consulted on important matters of state and justice. The statue of Amon might mysteriously indicate “yes” or “no” through movements, likely controlled by priests during processions, thus delivering the God’s judgment.

The Oasis at Siwa was one of the most famous oracles of the classical world and a major center for the worship of Amon, alongside his priesthood in Thebes. Its reputation for accuracy was so great that Alexander the Great sought its guidance as soon as possible:

Life of Alexander, Plutarch:

"The priest addressed Alexander in the manner of a god, and as some say, he greeted him as ‘Son of Zeus.’ … He asked if any of his father’s murderers had escaped him, and the priest replied that he must speak no blasphemies, for his father was no mortal."

Both Alexander and the Greek dynasty of the Ptolemies, who ruled Egypt after him, represented themselves with the horns of the ram, signifying their divine descent from Zeus.

Some Greek and Roman individuals in Antiquity did not fully understand the animalistic aspects of Zeus as depicted in Egyptian tradition. This issue is touched upon by Lucian, where the personification of Blame (“Momos” in Greek) sneers at Zeus, only for the Great God to refute him:

Deorum Concilium, Lucian:

Momos: "And you, Zeus, how can you bear it when they transplant a ram’s horns onto you?"

Zeus: "These things you observe about the Egyptians are truly shocking. All the same, Momos, the greater part of them has a mystic significance, and it is not at all right to laugh at them, just because you are not one of the initiated."

The Amon cult of Zeus was most commonly followed by the Libyans, even beyond the Greek colonies. They often synthesized this Egyptian aspect with Baal Hammon of Carthage.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Pythian Odes, Pindar

Histories, Herodotus

Life of Alexander, Plutarch

Deorum Concilium, Lucian

Egyptian Solar Religion in the New Kingdom: Re, Amun and the Crisis of Polytheism, Jan Assmann

Amun, World History Encyclopedia, Joshua J. Mark

Amun and Amen-Re, The Encyclopedia of Religion, C. J. Bleeker

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe