Names of Zeus: Atum

author: SG Karnonnos

Atum, one of the most ancient and significant deities in Egyptian mythology, stands at the heart of the Heliopolitan cosmogony as the self-created progenitor of the Gods and the universe. Revered as the "Lord of Totality" and the "Complete One," Atum embodies the concepts of creation, completeness, and cyclical renewal.

Less hidden than Amon yet fundamentally cryptic nonetheless, Atum’s symbolism permeates Egyptian religious texts, iconography, and temple rituals, reflecting his dual role as both the beginning and the end of existence. Atum’s mythological roles, his symbolic associations, and his enduring legacy in Egyptian theology are varied, present in core sources such as the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, and the Book of the Dead, as well as scholarly analyses by Egyptologists.

HELIOPOLITAN CREATION MYTH

Atum’s prominence originates in the cosmogony of Heliopolis (Iunu), one of Egypt’s oldest religious centers. According to the Heliopolitan tradition, Atum emerged from the primordial waters of Nun, the chaotic abyss that existed before creation. The Pyramid Texts (c. 2400–2300 BCE), inscribed in the pyramids of Fifth and Sixth Dynasty pharaohs, describe Atum’s autogenesis:

Utterance 527, Pyramid Text 600

Atum-Khepri, you became high in the sky; you rose as the Benben stone in the Mansion of the Phoenix in Heliopolis. You spat out Shu; you expectorated Tefnut. You put your arms around them, as the arms of a Ka, so that your Ka might be in them.

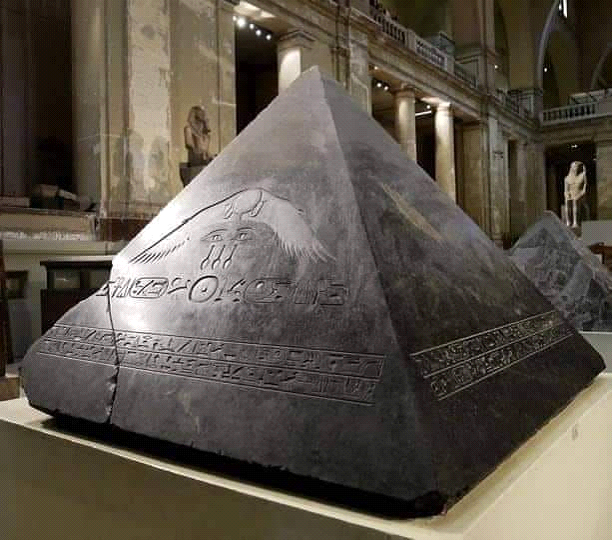

Atum was a primeval creator God in ancient Egyptian religion, central to the Heliopolitan creation myth. In the beginning [the Tsep Tepi, or “first occasion”], only the dark, formless waters of Nun existed. From this primordial chaos, Atum self-generated and emerged, often portrayed as arising on the Benben (a pyramid-shaped primordial mound, similar to a Chakra) that rose from Nun.

Uniquely, Atum was considered “the self-created” one, containing the potential of all life. He produced the first divine pair, Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture), from himself; Atum’s name derives from the root "tm," meaning "to complete" or "to finish." This etymology underscores his role as the God who contains all potentiality within himself. The Coffin Texts (c. 2100–1800 BCE) emphasize his completeness:

76, Coffin Text

I am Atum, the creator of the Eldest Gods. I am he who gave birth to Shu; I am that great He-She. I am he who did what seemed good to him, who took possession of the Two Lands from Nun, who gave commands to the Ennead.

Atum’s androgyny (referred to as the "great He-She") highlights his self-sufficiency, enabling him to generate life without a consort, but also to the distinct magnetic and electric polarities of the universe.

There was also a chthonic and death-related aspect to Atum. Pharaohs paid homage to Atum in their mortuary texts, aspiring to unite with Atum in the afterlife. The idea was that upon death, the king’s soul would travel to the heavens and merge with Atum in the setting sun.

In the Pyramid Text Utterances, the deceased king says, “I am your son; I have come to you, Atum,” seeking to sit on Atum’s throne in the sky. This reflects how Atum symbolized absolute sovereignty, both divine and royal. Indeed, one scholar notes that Egyptian creation mythology provided a theological charter for kingship, and Atum, as creator, was central to that charter.

SYMBOLISM OF ATUM

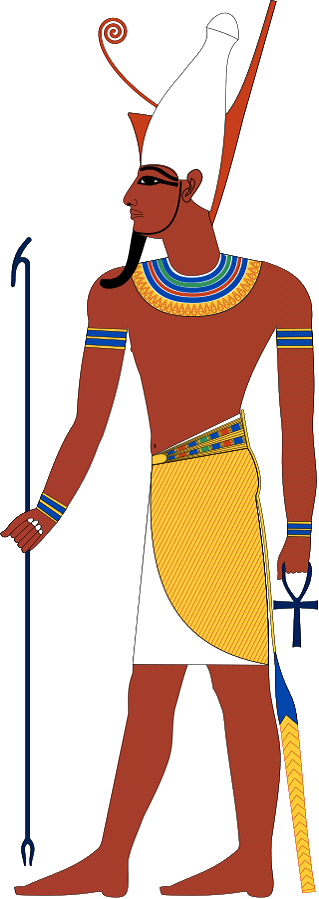

Artistically, Atum was usually depicted in human form as a man wearing the pschent (double crown) of Upper and Lower Egypt, also hinting at his control over the two realms of existence. The two sides of order and chaos are represented in the crown, showing his ultimate symbolism as Lord of Ma’at.

He often carries a was-scepter (representing power) and an ankh (representing life), emphasizing his authority over creation and life-giving capacity. One of the few distinctions in art between Atum and a pharaoh is that Atum can be shown with a divine beard (curved at the tip) instead of the straight beard of kings, related to the Fibonacci Sequence.

He is frequently shown enthroned, as befits a creator-king of the Gods. In certain contexts, Atum had specialized iconography: in the underworld, he might be depicted as an aged man leaning on a staff (showing the sun’s weakness at day’s end) or even with a ram’s head, a form he takes in the Duat as a protector, associating him with Amon.

Atum’s association with the sun also meant he was depicted as a scarab beetle in some solar cycles; the scarab (Khepri) symbolized the morning sun’s rebirth, and Atum as the scarab underscored his role in the continuous regeneration of the sun. In Egyptian eyes, these varied images all expressed Atum’s attributes: creative power, kingship over creation, and the guarantee of renewal.

Atum’s emergence from Nun atop the primordial mound is symbolized by the Benben stone, a pyramidal or conical object that became the prototype for obelisks and pyramidions, and also represents the Chakras. The Benben represented the first solid land and the nucleus of creation. In temple architecture, the innermost sanctuary (the Naos) housing the cult statue was seen as a microcosm of this mound, linking Atum’s creative act to daily rituals.

He was occasionally depicted as a lion or an ichneumon, a stylized Egyptian form of a mongoose. The ichneumon, a creature that kills snakes, reinforced his role as a protector against chaos. The lion, on the other hand, symbolized solar power and kingship, linking Atum to the pharaoh’s divine authority.

In his nocturnal form, Atum was depicted as a serpent: a symbol of regeneration and the underworld. The Book of the Dead (Spell 175) describes Atum’s final act of dissolution:

Spell 175, Book of the Dead

I shall destroy all I have made; this land shall return to Nun, to the flood, as in its original state. But I shall remain with Osiris; I shall transform myself into another serpent that men do not know and the Gods do not see.

This serpentine form underscores Atum’s role as both creator and destroyer, embodying the cyclical nature of time.

Atum’s self-oriented act of creation, often euphemized as "using his hand," symbolizes self-contained creativity. The hand became a

hieroglyph for action and power. In the Bremner-Rhind Papyrus

(4th century BCE), Atum declares: I copulated with my fist; I joined my hand to my mouth; I came into my own

mouth. I sneezed out Shu; I spat out Tefnut.

This paradoxical imagery, barren yet fertile, reflects the Egyptian understanding of creation as an act of divine will transcending mere biological norms.

Moreover, Atum had a rich animal symbolism that conveyed his powers. His sacred animals included the serpent of the Kundalini, the lion [symbol of all royal and solar prerogative], the bull, representing control of the mind, virility, and solar royalty (such as the black Mnevis bull of Heliopolis, which was sacred to Atum), the lizard, and the ichneumon or mongoose, known for fighting snakes. The contradictory imagery of his animals demonstrates his connection to creation, destruction, and rebirth.

Each creature reflected an aspect of Atum: for instance, as a lion, Atum was a fierce protector; as a serpent, he was the mysterious embodiment of eternity; as a bull, he was a procreator and king. Even as a baboon, he took on the role of a defender, shooting at the agents of chaos.

One notable example is the symbol of the Phoenix. The Egyptian Benu bird, tied to Atum and related to the Stone, was said to rise from the waters of Nun and alight on the Benben stone, crying out to inaugurate creation. This symbolism was copiously stolen by Christians and various deviants in Egypt later on.

These varied symbols reinforced Atum’s image as a deity who was present in all forms of life, animal and human, but he ultimately transcended them as the singular master of creation. Atum’s symbolism thus operated on cosmic, political, and personal levels, making him one of the most symbolic Gods in the Egyptian pantheon.

TEMPLES OF ATUM

Atum’s cult was firmly established in Iunu. He was venerated both as a solar deity and as the primordial father of the Pharaoh. Rulers of this era often incorporated Atum into their royal epithets and pyramid rituals. For example, Pharaoh Unas (5th Dynasty) has texts saying he will ascend to the sky and sit on Atum’s throne, emphasizing closeness to the God.

Middle Kingdom pharaohs like Senusret I and Amenemhat III refurbished Heliopolis’ temples and added obelisks celebrating Atum. There was an increasing emphasis on Atum's role in assisting Ra's battle against the serpent Apep and Atum defeating the serpent Sepa, which is shown elaborately in the Book of Gates. Other imagery found in tombs from this period shows Atum presented adjacent to these serpents.

Though Heliopolis remained Atum’s primary cult center, his worship spread to Thebes and the Delta. Temples featured statues of Atum as a man wearing the Double Crown, symbolizing his dominion over Upper and Lower Egypt. In reliefs, he often holds the was-scepter and the ankh.

Some Ptolemaic temples in Upper Egypt also honored Atum; for example, at Dendera, a Greco-Roman era temple complex, Atum is included in cosmological scenes and hymns alongside other creator deities.

UNION OF ATUM AND AMON

In the New Kingdom, there were cults attributed to Atum, such as the Theban royal High Priestesses known as the Divine Adoratrices of Amon, who acted as the Hand of Atum in temple rituals. This shows that there was a symbiotic relationship of the two Gods shrouded in symbolism.

By the Roman Period, Atum was sometimes merged into the figure of Zeus Ammonas or Jupiter in interpretatio graeca-romana, or into forms of Zeus-Helios (Zeus of the Sun) during Roman imperial visits to Heliopolis. He was frequently represented with ram horns.

We see, for instance, on some Roman coins and inscriptions, Jupiter-Helios-Atum conflated as a single deity. Emperor Augustus, in dedicating a stele, invoked “Jupiter who rises from the eastern sky,” referencing Atum-Ra.

There was also a philosophical interpretation. Plutarch, in On Isis and Osiris, mentions a concept of an Egyptian supreme deity who remains after all else is destroyed, likely alluding to Atum’s role at the end of time. This helped Hellenistic thinkers frame Atum as a symbol of an enduring prime principle, akin to their idea of the Logos or primal God.

PHARAOH, SON OF ATUM

Pharaohs claimed descent from Atum to legitimize their rule. The Pyramid Texts (Utterance 600) state:

Utterance 600

The king is the son of Atum, who loves him, who has given him birth, that he may be on the throne of Atum forever.

By associating themselves with Atum’s creative power, Pharaohs positioned themselves as upholders of Ma’at (cosmic order). Many Pharaohs used the epithet “Son of Atum” as part of their titulary, even long after political power had shifted away from Heliopolis and toward Thebes.

As the first God-king (the one who ruled before earth had Pharaohs), Atum was viewed as the divine prototype from whom earthly Pharaohs inherited authority. Pharaohs explicitly aligned themselves with Atum. The title “Son of Atum” was used by kings to stress that they were the offspring of the original creator.

CREATOR FESTIVALS

Atum’s festivals, such as the "Feast of the Ennead," involved processions and offerings of bread, beer, and incense. The Temple of Atum at Heliopolis housed a sacred tree (the ished), where the God’s presence was believed to dwell.

In Thebes, the Opet Festival and other state rituals occasionally invoked Atum alongside Amun. A papyrus from the Late New Kingdom suggests Atum played a central role in the New Year’s festival: as the year regenerated, the king’s role was renewed by Atum’s blessings.

ENEMY CONTEXT

Many of Atum and Amon’s attributes, along with the advanced mysteries of Zeus from Greek sources, were stolen by Christianity, particularly the idea of alpha and omega and the logos. The lunatic named Origen claimed knowledge of the phoenix myth and shamelessly forced it into the myth of ‘Christ.’ Other aspects made it into the Gnostic literature, such as the so-called ‘Autogenes.’

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Book of the Dead chapters 15, 17, 175, Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts

Ancient Gods Speak, Donald B. Redford

Atum the Creator God, kemetexperience

On Isis and Osiris, Plutarch

The Phoenix and the Early Church, Daniel Tompsett, Foundations

Handbook of Egyptian Mythology, Pinch

The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, Richard H. Wilkinson

Ancient Egyptian Creation Myths: From Watery Chaos to Cosmic Egg, Glencairn Museum

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe