Names of Zeus: Nzazi

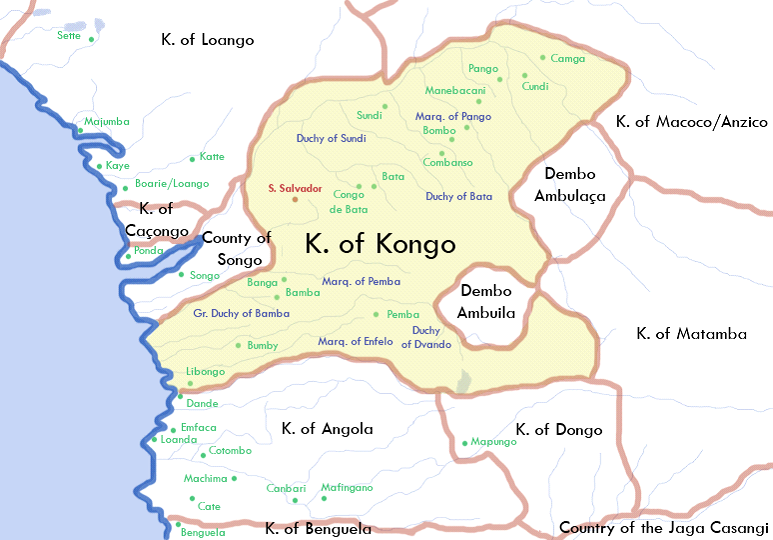

The Bakongo people, whose ancestral lands span modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo, Angola, and Gabon, possess a spiritual tradition tied to Nzazi, the God of thunder and lightning, who stands as one of the most complex figures.

Revered as both a life-giver and a destroyer, Nzazi embodies the duality of nature and serves as a moral arbiter in Bakongo religion. The role He exemplifies in Bakongo spirituality is more complex, offering insight into how this Deity reflects the Kongo people’s understanding of the natural world and ethics.

NZAMBI MPUNGU

Bakongo theology centers on Nzambi Mpungu, the supreme Creator God, who delegates authority to lesser deities and spirits named bisimbi, roughly analogous to orishas:

Oxford Reference

God of the Bacongo people of Angola. Identified with the Sun, Nzambi is self-existent, almighty, and ‘knows all.’ The Bacongo say: ‘He is made by no other; no one beyond Him is.’ Nzambi, ‘the marvel of marvels,’ is a kind Deity who ‘looks after the case of the poor man.’ Indeed, the sky God appears to show kindness even to the most destitute members of society. Incapable of evil or wrongdoing, He ‘is just and merciful,’ the ruler and sustainer of the universe, a fount of goodness.

Individual differences, however, the Bacongo attribute to Nzambi. Not only does He create individuals, but He also gives them different tastes and soul qualities. They say: “What comes from Heaven cannot be resisted.” A special relationship is said to exist between the Creator Deity and man, sometimes expressed as: “Man is God’s man.”

This is a typical theme of Bantu mythology. Nzazi is said to be a bisimbi of the greatest power.

According to Bakongo cosmology, the universe originated from an infinite, lifeless void known as mbûngi. From this primordial emptiness, the supreme Deity Nzambi Mpungu called forth a primordial spark of fire, Kalûnga, which began to expand until it filled the mbûngi entirely.

As Kalûnga grew beyond containment, it erupted into a cosmic explosion, cataclysmically dispersing superheated elements across the cosmos. This energetic outburst forged the foundations of the universe, sculpting the stars, planets, and celestial bodies into being.

Within this tradition, Kalûnga is revered not only as the catalyst of creation but also as the universal force driving all motion and change. The Bakongo worldview emphasizes that life itself depends on perpetual transformation and dynamic motion, principles embodied by Kalûnga. Notably, Nzambi Mpungu is also venerated as Kalûnga Himself. He embodies the divine principle of change that sustains cosmic and earthly cycles.

Such cycles are related to the rising, peak, setting, and invisible phases of the Sun, which the Bakongo peoples correlate with all stages of life and the creation of the world. Many of these cosmologies are similar to that of Atum in Egypt, including the solar aspect of fourfold rejuvenation.

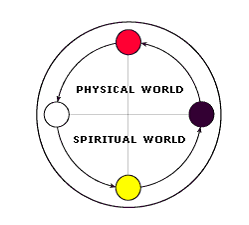

The Bakongo split the world into the physical realm of Ku Nseke and the spiritual realm of Ku Mpèmba. A line of mysterious depth called the Kalûnga Line separates these two worlds. All living things exist on one side or the other. Simbi spirits are believed to transport Kongo people between the two worlds at birth and death.

LIFE-GIVER

As the bringer of rain, Nzazi is essential to agricultural cycles. The Bakongo’s lifestyles are strongly dependent on farming. They view thunderstorms as blessings that replenish the soil. Rituals invoking Nzazi’s rain often accompany planting seasons, ensuring fertility and abundance. In this role, He is closely associated with Nzambi Mpungu’s creative power. He channels water, the symbol of life, from the heavens.

In times of drought, communities of Bakongo people gather to dance, drum, and chant, calling on Nzazi to send rain. These ceremonies often involve the use of iron bells and rattles with thunderous sounds.

A myth credits Nzazi with carving rivers and valleys through lightning strikes, shaping the topographic grooves in the Earth. This aligns Him with creation itself, positioning thunderstorms as tools of both destruction and renewal.

ORAL TRADITION

One popular myth tells of a village chief who hoarded resources during a drought, refusing to share with his people. Nzazi, angered by this selfishness, summoned a storm that struck the chief’s granary with lightning, reducing it to ashes. The chief repented, and rain soon followed, reviving the land.

This story underscores Nzazi’s role in enforcing communal ethics and the consequences of greed, but it is extremely similar to other myths involving Zeus from around the planet.

Another narrative describes Nzazi as a warrior who battles malevolent spirits (ndoki) causing chaos on Earth. His thunderclaps are the sound of his celestial weapons clashing with dark forces, while lightning illuminates the path to righteousness.

BANGANGA

The main individuals of Bakongo religion are healers named Banganga or Nganga, which means "expert." Within the Kingdom of Kongo and the Kingdom of Ndongo in the Renaissance era, the priests were noted to have undergone complex training, lasting years, with detailed oral codes. Kongo was one of the most complex and advanced kingdoms in Africa, centered around the city of Mbanza Kongo.

They also underwent training to commune with ancestors or spirits such as Nzazi. Nzazi is held to be important in guiding a person in their setting time of life to Ku Mpémba, the spiritual world.

They played a large role in resisting João I, João II, and Afonso I, who forced Christianity onto the Congolese through Portuguese contact. Many continued to resist the efforts of the Capuchin priests to enforce Christianity onto the Kingdom well into the early 1800s.

SYMBOLS OF NZAZI

Nzazi is often described as a canine figure, or a man surrounded by twelve hounds that possibly represent the Labors. Mbwa Nzazi, the dog of Nzazi, is used to control lightning and thunder, to keep people away from what they can cause.

For the Baluba, Nzazi, “the Lightning Bolt,” represents an animal. It is described as a black goat with a peacock’s tail that produces flames when opened. In the drier seasons, it supposedly lives inside caves, yet during the rainy season, it rises to the surface. It always moves like a rumble, forming the thunder. It often launches itself toward the ground with the aim of touching an object, an animal, or a man, to absorb its energy and feed itself.

The fire of Nzazi comes through lightning that strikes palm trees and fruit trees. When struck by this lightning, people are forbidden to touch them. This is determined by Nkisi Nzazi through the Nganga. When passing close to said tree, the Nkisi Nzazi will be freed from a curse. The trees struck by Nzazi are used as materials for making amulets and sacred objects.

Nzazi is depicted wielding a thunderous weapon, as with nearly all representations of Zeus. This tool represents his ability to split the sky and strike the Earth with precision.

The towering kapok tree is believed to attract lightning. It is considered therefore highly sacred to Nzazi. Its hollow trunk is thought to house his energy, and rituals are often performed at its base.

After storms, the rainbow (nkangi) is seen as Nzazi’s “bridge,” signaling the end of his fury and the restoration of peace. The rainbow is also a symbol of many other supreme Bantu Gods, suggestive of a shared tradition.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Narrative of an expedition to explore the river Zaire usually called the Congo in South Africa in 1816

Por James Kingston Tuckey , Christen Smith

Two Trips to Gorilla Land and the Cataracts of the Congo, Richard Francis Burton

African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry, Ras Michael Brown

Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular, Wyatt MacGaffey

Folk-lore - A Quarterly Review of Myth, Tradition, Institution, and Custom, David Nutt

NPS Ethnography: African American Heritage & Ethnography

CREDITS:

Karnonnos [SG]

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe