Names of Zeus: Raijin

Raijin, also known as Raiden, Narukami, and Kamowakeikazuchi, is a deity in Shintoism associated with thunder, war, power, saving rains, agriculture, and storms. He takes on a more chthonic role compared to many of the representations of Zeus, casting lightning bolts onto people as the arbiter of Yomi, the Realm of the Dead. His appearance is stark and terrifying.

In Kanji, he is represented as 雷神, a combination of 雷 (kaminari), meaning “thunder,” and 神 (kami), meaning “god” or “spirit.” Thus, he is simply the Thunder God. Other names are Kaminari-sama (雷様, “Lord Thunder”), Raiden-sama (雷電様, “Lord Thunder and Lightning”), Narukami (鳴る神, “The Resounding God”), and Yakusa no Ikazuchi no Kami (厄災の雷の神, “God of Storms and Disaster”).

The distinct difference between this representation and the serene visage of the Jade Emperor or Shiva warrants a certain explanation of how Raijin is a representation of Zeus. Many, by visual factors alone, may misunderstand that this entity is considered evil.

The Japanese also venerated various other deities, such as the Creator God of a Triad named Ame-no-Minakanushi in the Nihon Kojiki and the regional Ajisukitakahikone, who can be equated with Zeus, having similar attributes in more mysterious and humanized forms, respectively.

In addition, the famous ancestral Gods of Japan, Susanoo, Tsukuyomi, and Amaterasu, siblings of Raijin who appear from the washing of Izanagi, represent the triad of Zeus, Aphrodite, and Apollo in a more interchangeable and occult manner than most pantheons. The divisions of the three are more fluid.

SYMBOLISM OF RAIJIN

It has been imparted to me by Gods numerous times that much of the innate symbolism of Japanese culture lies in death and rebirth. Beyond the typical Shinto worship of nature, there is a strong undercurrent of this in the way Raijin and seven other thunder kami are represented as emerging from the eight cores of the Goddess Izanami’s body as she descended into the Realm of the Dead.

The Zevist could understand that this concept relates to the spiritual awakening of an individual, where ‘God’, in full flashes of lightning, suddenly starts to appear when Chakras are activated correctly.

Another early myth in the Nihon Shoki and various regional legends associates Raijin with fertility and clan origins. For example, the Kamo clan of Kyoto believed their ancestral deity, Kamowakeikazuchi, descended from heaven in a flash of lightning, a legend commemorated at the Kamigamo Shrine.

In the earliest legends, Raijin is considered serpent-like in his shape and form. This mythology was later shifted toward the separate Ryujin dragon figure.

The original depictions of Raijin in Japanese culture were not animalistic nor associated with a fearsome visage, but during the Kamakura period, the influence of the perennial wars in Japan and the similar Chinese lightning deity Leigong began to shift his attributes to those of being awe-inspiring and terrifying.

Representations of Raijin and Fujin became prolific in the Shogunate period as a result of mass printing of ukiyo-e works dedicated to the duo of Gods. Hence, he was revered as one of the most popular deities of Japan in its popular culture during that time.

Visually in ukiyo-e, he is often represented with the horns or ears of an ox or bull. In addition, he is often shown with a mantle of the skies, similar to that of Zeus, which loops over his shoulders and behind his head.

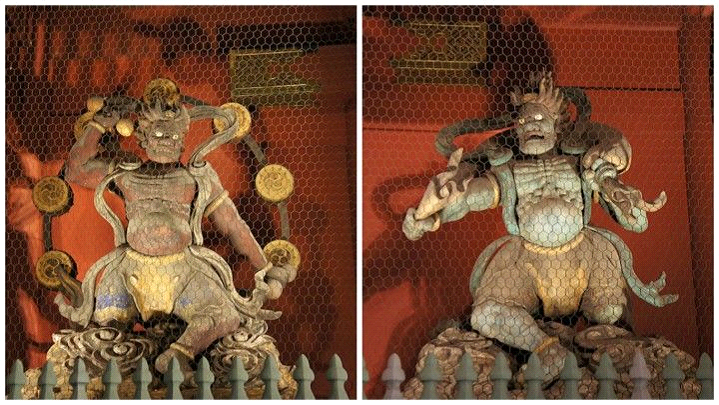

In art and shrine statuary, he appears as a muscular, horned Demon (an oni-like figure) riding atop dark clouds. He brandishes mallets or drumsticks in raised arms, poised to strike a circle of drums that encircles him. Each drum often bears the tomoe motif (a type of comma-shaped swirl), an ancient symbol associated with thunder and whirlwinds. Striking these drums, Raijin “makes” thunder, an image that directly links to the auditory experience of storms. This imagery first solidified in the Kamakura period and has remained iconic ever since.

Despite this fearsome visage, Raijin is also depicted in endearing ways. In popular lore, he has a companion creature called the raijū (thunder beast), a small magical animal (variously described as a tanuki-like creature) that sleeps in human navels. When Raijin needs to wake his pet for a storm, he shoots lightning arrows from the sky to startle the raijū out of its navel hiding spot. This may be allegorical of activating the Lower Chakras.

Typically, Raijin is also referenced as carrying hammers or mallets, which he uses to impose himself.

He is also seen in the texts as a protector deity of Japan as a whole. In one legend, Raijin is shown to defend Japan against the invading Mongols. In this legend, the Mongols are driven off by a vicious storm in which Raijin is in the clouds, throwing lightning and arrows at the invaders.

LORD OVER ALL

Raijin is unwilling to listen to the priests, monks, and even the Emperor of Japan. This is an allegorical and polite way of showing his primacy over the cosmos. He is only shown as being able to consort with divine and ascended beings, which in Japan was increasingly interpreted through a Buddhist lens.

In the Nihon Shoki, he strikes a man with lightning who attempts to cut down his sacred tree on the orders of Empress Suiko. It is only by invoking imperial necessity that he is totally pacified.

GIVER OF RAINS

Rains are bestowed by his will. Raijin was known in the Japanese texts as the savior of farmers and a tutelary deity of agriculture. When droughts appeared, the farmers would reason that Raijin had been imprisoned. A lightning strike on a rice paddy was taken as a sign of a bountiful harvest to come.

This belief was so strong that many Japanese peasants thought lightning itself fertilized the rice fields. Accordingly, farmers would offer prayers and hold rain-invocation rituals (amagoi) at shrines dedicated to Raijin to beseech his blessing of rain in times of drought.

Clearly, Raijin’s wild wrath demanded respect and appeasement. In many areas, special rites were performed to ward off or expel the thunder God’s malice during storms: for example, villagers might split bamboo or clang metal objects during thunderstorms as a symbolic exorcism (kandachi-oi) to drive away Raijin’s frightening powers.

To this day, Raijin is associated with electrical goods in Japan, showing his mantle as a very modern deity, though sometimes paired with Fujin in a comedic manner.

SHRINE WORSHIP

Numerous Shintō shrines across Japan are devoted to Raijin or related thunder deities, attesting to his importance.

One example is the Kanamura Wake Ikazuchi Jinja in Tsukuba (Ibaraki Prefecture), locally called “Raijin-sama,” which is regarded as one of the three great Raijin shrines of the Kantō region and was established by the Japanese emperor in the 9th century. At this shrine, Raijin is explicitly honored for his two faces: a “strong side” that unleashes thunder to punish wrongs, and a “gentle side” that brings rain to nurture life, making him especially popular among those praying for agricultural fortune.

Seasonal festivals are still held here every spring and autumn to celebrate Raijin’s benevolence and to ensure good harvests.

Another shrine of similar symbolism and importance is the Kamo Shrine in Kyoto (Kamigamo), which enshrines the kami Kamowakeikazuchi, and from ancient times held elaborate rituals to appease this God for the sake of the nation’s wellbeing. The Emperor was compelled to ride a white horse to do so. Historical records note that as early as the 6th century, imperial envoys were sent to the Kamo shrines to calm the thunder deity after stormy weather caused crop failures.

In the Edo period (1603–1868), Raijin worship remained vibrant in both state rites and folk practice. The Tokugawa Shogunate supported grand festivals for popular deities, and thunder Gods figured in local festivals, especially in agriculturally important areas. Many Raiden shrines were founded or rebuilt during this time. For instance, the Raiden Shrine in Kiryū (Gunma) was established in 1677 to honor Honoikazuchi, the associated thunder deity born from Izanami’s chest.

Locals credited the kami with guarding their town and crops, reflecting a common belief that Raijin could protect communities if properly venerated. By this time, Raijin was affectionately called Kaminari-sama (“Lord Thunder”) by ordinary people.

AME-NO-MINAKANUSHI

The great ancestor of Raijin, Susanoo, Tsukuyomi, and Amaterasu is Ame-no-Minakanushi, the primordial Creator God of the universe. This God appears in a narrative of the Nihon Kojiki as a mysterious creator deity.

BUDDHISM

Rather than being replaced by Buddhism, Raijin was said to have been “subdued by the Buddha” and turned into a guardian of Buddhist temples in Japan, similarly to Sakra, but in a more animalistic guise. Certain contexts in Japanese religion convey him as a tutelary spirit.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Shoki

The Koijki

Raijin, Encyclopedia of Shinto, kokugakuin.jp

Nijuhachibushu, 28 Legions of 10,000-Armed Kannon, plus Raijin & Fujin, onmarkproductions

Raijin, mythopedia

Legend in Japanese Art: A Description of Historical Episodes, Legendary Characters, Folk-lore, Myths, Religious Symbolism, Illustrated in the Arts of Old Japan, John Lane

CREDITS:

Karnonnos [SG]

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe