Names of Zeus: Shango

Shango, also known as Xango, is the personification of thunder, farming, justice, storms, dance, and masculine virility in the Yoruba, Dahomey, and Ewe religions that originate from modern-day Nigeria, Benin, Cameroon, and Togo. He is also known as Sogbo or Hevioso in the Fon religion of modern-day Benin, where Voodoo originated.

The God of Storms is represented prolifically in many of the New World religions of the Black diaspora, such as Santería in Afro-Latin communities, Candomblé in Brazil, and Voodoo in Haiti, Louisiana, and many other environs. He also appears in distinctive traditions of Trinidad and Cuba that bear his name alone.

Many of his aspects are verbally passed down and not always in complete alignment with one another, but a strong picture emerges of this God from the Yoruba lands.

SYMBOLISM OF SHANGO

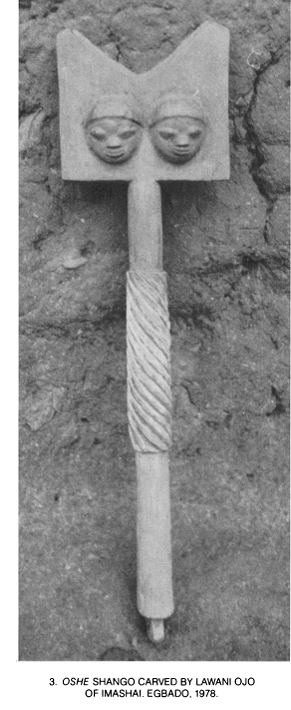

As in many other traditions, Shango is represented as an Orisha with a single or double-headed axe, typically either on his head or adjacent to his feet. He is often depicted with this symbol, which represents the power of lightning and control over the elements. His colors are usually red and white, colors that held significant importance in Egypt.

Occasionally, however, he is represented in a more androgynous bodily form, which is considered allegorical of the Orishas’ nourishing influence and the balance of masculine and feminine forces in the soul. Of all the Gods, he wields the ase (divine force), akin to witchpower, the most liberally. This androgyny is also reflected in his traditional priests, who wear the shaved, braided, and high hairstyles of women on special occasions. Interestingly, this hairstyle, when worn by men, is associated with the trance state and the medicinal aspect of Shango during mass rituals; it is forbidden for men to wear in other contexts.

His physical beauty and virility are always emphasized in Yoruba cosmology, as is his tendency to anger quickly and act capriciously. Shango represents the power of nature itself, more centrally than other representations of Zeus. Much like Raijin, the rhythms of the Iyá, Itótele, and Okónkolo drums call down his energy and embody his powers.

The Yoruba believe Shango creates thunder and lightning by casting down “thunderstones” from heaven to earth. Anyone who offends Shango is struck with lightning speed. When a strike occurs, followed by peals of thunder, ancient Shango priests would scramble to search for thunderstones, or the “thronestone,” which were believed to have special powers:

Yoruba Prayer to Shango

On’-ile ina!

A da ni niji

Ina osan!

Ina gun ori He feju!

Ebiti re firi se gbi!

The Lord of the House of Fire!

One who causes sudden dread!

Noonday fire!

Fire that mounts the roof and becomes glaring!

The killing weight that strikes the ground with resonant force!

Shango is honored in a sacred dance that reenacts all his deeds and achievements, not dissimilarly to Shiva. Worshippers in Yorubaland still wield the oshe, or axe of Shango, in a symbolic mass dance, his dual faces elaborating certain mysteries:

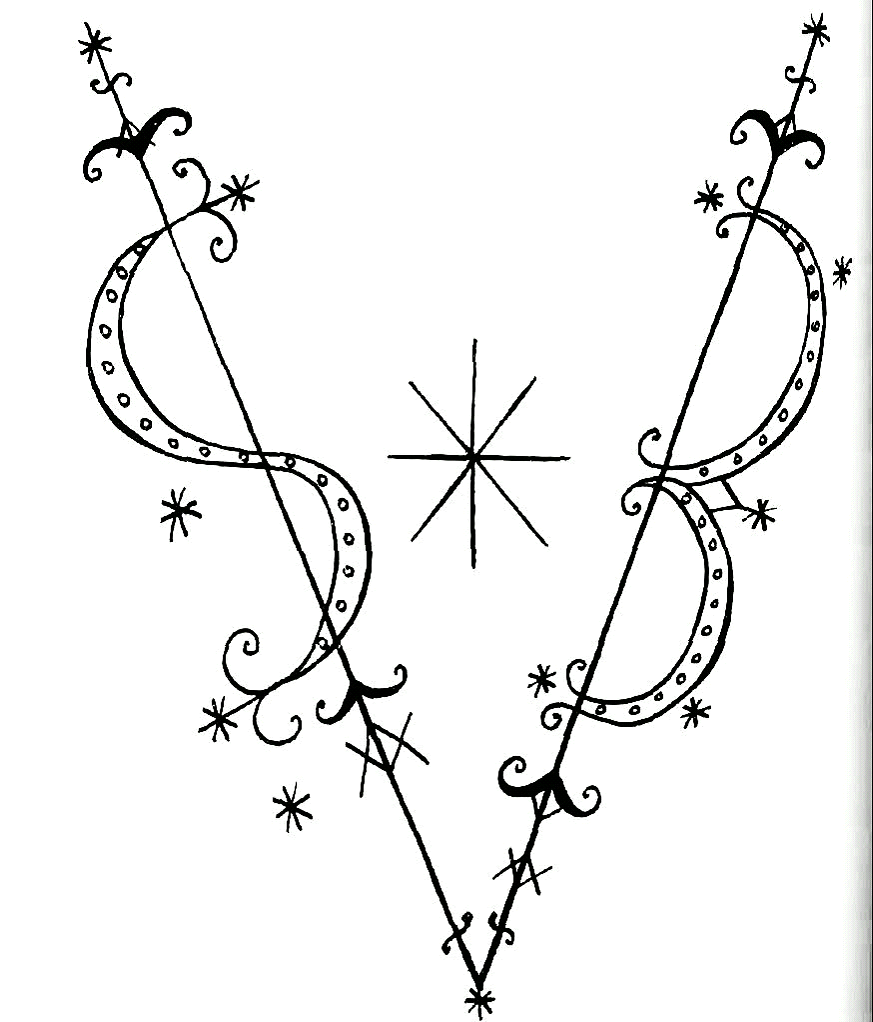

Shannon pointed out to me that the related Veve of Hevioso represents the horns of the Ram:

In Santería, particularly, Shango is consistently associated with the ram and the color red, symbolic of his connection to Amon and Zeus, as well as the sign of Aries and the spring equinox. He is often invoked for success in sexual matters, being known in the myths as amorous. His day is represented as either Friday or Saturday, but often Thursday in Africa.

In Brazilian traditions, Shango is portrayed with a bronze crown, signifying his precedence among the Orisha. The four major Nigerian rivers (chief among them the River Niger) are also considered Shango’s wives, alluding to his mastery of the elements.

THE EARTHLY SHANGO

In most narratives, Shango is held to be one of the major ancestors of the Oyo Empire. He is regarded as the third Alaafin (Custodian of the Palace), who brought all forms of prosperity and power to the realm. A warlike and strong ruler, he caused many of Oyo's enemies to fear him. In the Yoruba understanding, the fearsome Alaafin was married to Oya (Lilith) and Oshun (Astarte). It is due to Oya’s intrigues and persuasion that Shango decided to take power.

The Shango cult played a vital role in state administration. The Alaafin’s position as representative of Shango was fully exploited as a means of reinforcing his authority. The cult was spread to every town under Oyo influence and organized in a hierarchy centered in the palace at Oyo. The Alaafin’s Ajales were often themselves Shango priests.

Trinidad Yoruba, Maureen Warner-Lewis

His rule ended either when the palace itself was struck by lightning, prompting a type of apotheosis, or when he was driven out by another ruler. Hence, in Yoruba traditions, Shango was a physical being who became an Orisha. He was originally a king of the Oyo Empire. He brought prosperity to the realm and later committed suicide by hanging, afterward revealing himself to the Oyo people as having taken his place among the Orisha. Fon narratives show a similar story about Hevioso.

To this day in Nigeria, Shango is called upon during coronations to bestow the king with righteous power and the proper use of justice. In Santería, rites are often concluded by naming him the King:

Lukumí ritual

Kabiosile Changó!

Hail to the King, Shango!

OLUDMARE

The great God behind all the Orisha spirits, Oludmare (Osanobua among the Edo peoples), represents the concept of Satya or Cosmic Truth. Oludmare is in everything, and yet beyond everything at the same time. It is known that this force designated Shango as the strongest and most powerful of the Orishas. Among the Yoruba, He is also associated with rainbows and prisms of color that often appear after the storm.

As the Supreme Being at the apex of this divine cosmic hierarchy, Olodumare [Nana Buluku, Nazambi Kalunga, or Onyankopon] is the Owner of the Skies, the Source of all existence, and the originating power behind the world of spirits and human life. The name Olodumare is a combination of olo, odu, and mare. Olo odu means “owner of odu,” the principle that underlies the operation of the universe, and mare is “light” or “rainbow.”

Afro-Caribbean Religions, Nathaniel MurrellDIVINATION AND ÒRÚNMÌLÀ

The earthly emanation of the Orisha, named Òrúnmìlà, is held to have created all systems of divination, traveling the world to find the best systems and constructing the Great Temple of Ife-Ife. Several legends suggest Shango passed this ability to him in exchange for the gift of dancing, showing Shango’s identity as a God of Fate:

The Way of the Orisa, Philip John Neimark

Sango's powers of empathy and intuition cannot be overstated. Early oriki (little prayers and stories) suggest that at one time it was Sango who possessed the divination board and the secret of casting the future. In these stories it is said that because of his inborn ability to sense future events, Sango felt no need to use the physical equipment and techniques, and so traded them to Òrúnmìlà in exchange for the gift of dancing.

Òrúnmìlà himself is expressed through the Rites of Divination, Ifá. Divination is extremely important in Yoruba religion and functions as a major religious rite in itself. It is held to be approximate to communicating with Divinities, not merely symbolic or intercessory. Ifá is not only practiced in Africa, but also widely among the diaspora:

Afro-Caribbean Religions, Nathaniel Murrell

The popular Ifá divination system, common among the Yoruba, Fon Ewe (Dahomey), Ebo, Igbo, and other peoples of West Africa, is not only alive in Cuba, Brazil, and Trinidad, it is an academic and cultural pursuit both inside and outside the region.

The system of divination elaborates what will occur to the worshipper if they change little about their life. The symbolism of Òrúnmìlà in following Ifá allows the practitioner to achieve what is called títété (alignment of soul). Meditative states are considered essential, and in Yoruba understanding, it takes years of initiation and practice to achieve a proper state.

The priests and priestesses of Yoruba religion are taught up to 1,680 verses, or symbolic codes, expressed through sayings, by heart, paralleling the verbal systems of the Celts. There is evidence that some of these sayings came from Egypt itself, having major commonalities with Egyptian texts.

Shango is associated with the verses that deal with rulership, victory in battle, and the consequences of arrogance or misuse of power. His influence in Ifá often appears in cases where justice, strength, and balance are needed, as he is known for his fair but severe judgments. Red thunderstones (edun ara), believed to be remnants of his lightning, are used in rituals and sometimes appear in divination.

CORRUPTION

With the upheaval and prohibitions of Paganism that came with Transatlantic Slavery, many were obliged to worship the “saint” named Barbara, whose father was struck by lightning as he beheaded her for converting to Christianity. The androgynous characteristics of Shango were also contributors to this type of confusion.

To this day, many New World religions hybridize Shango with this saint, which is a dangerous practice. We at the Temple of Zeus ask that one’s practice remain focused fully on the God.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sàngó in Africa and the African Diaspora, Tóyìn Fálọlá, Joel E. Tishiken and Akíntúndéí Akínyẹmí

Afro-Caribbean Religions, Nathaniel Murrell

The Way of the Orisa, Philip John Neimark

Art and Trance Among Yoruba Shango Devotees, African Arts, Margaret Thompson Drewal

Trinidad Yoruba, Maureen Warner-Lewis

CREDITS:

Karnonnos [SG]

Shannon (assistance with Veve and Levioso, symbolism)

Warlock666 (Shango narrative elements, Trinidad Yoruba books)

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe