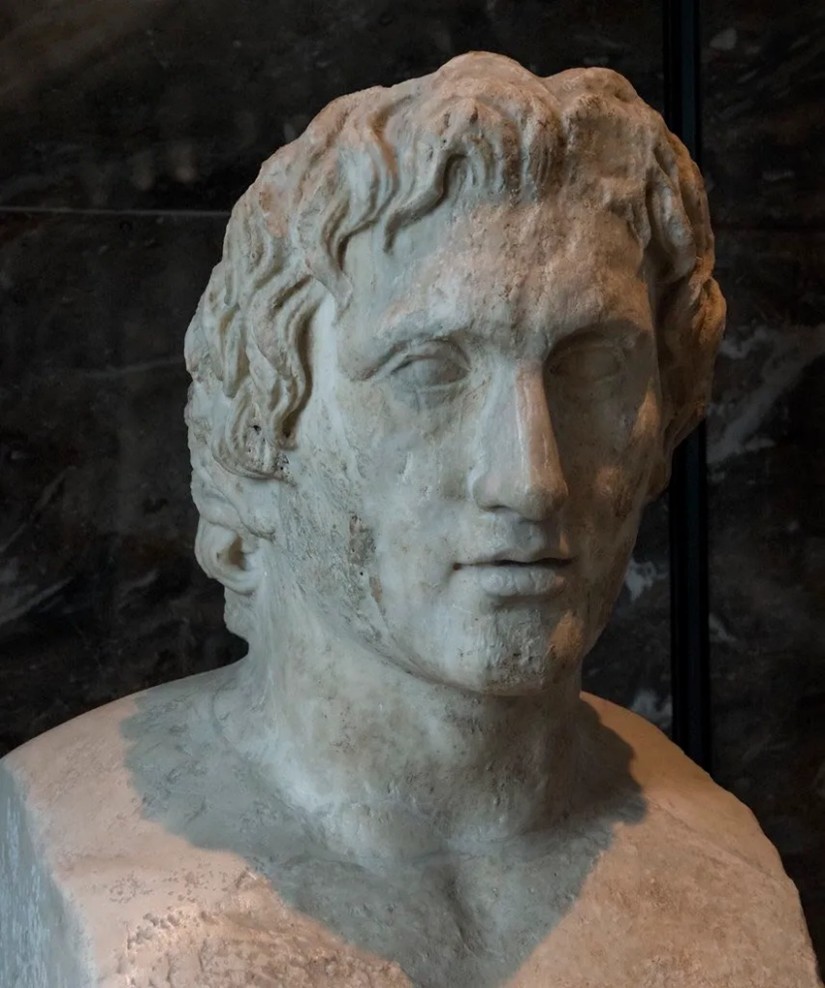

Alexander

Son of Zeus

To date, no monarch in the world is as radiantly emblematic of heroism as Alexander the Great, nor as deserving of such a title. Years and years after his Macedonian phalanx marched across the lands, his name still reverberates throughout the known world. His ferocious personality and perennial drive to accomplish the impossible have made his name a byword for masculine power, bravery, and struggle across the aeons.

Alexander can be said to be one of the singular individuals in history to inaugurate an entirely new era [the Hellenistic Era] through his achievements. The might of his armies and the depth of his search for knowledge spread ancient Hellenic culture and religion throughout the core of Eurasia. Due to his colossal achievements, the sheer spread of Greek culture extended from the Straits of Gibraltar to the outskirts of the Chinese kingdoms, enduring for more than seven hundred years.

BOYHOOD

He was born the son of King Philip II of Macedon, and through Philip he was known to be a descendant of Hercules.

King Philip had many major achievements to his name: he reformed the Macedonian army root and branch, placing emphasis on the phalanx that Alexander would later use to the fullest extent, and he pioneered the use of siege warfare and shock tactics.

The king created many urban centers in Macedonia by moving people out of their ancestral villages. Tribal enemies of Macedon were destroyed; he had conquered major parts of Thrace and Illyria. The voracious king had begun to incorporate much of Greece into his realm and had started to assert Macedon’s independence from its traditional master, Persia.

Alexander’s mother, Olympias, was a fierce woman of major note. She was the sister of the King of Epirus. The mysterious princess was also a known occultist and practitioner of Orphic rites, holding a major position in a significant cult of Cybele from Mount Haemus in Thrace. She was rumored to sleep on a bed of venomous snakes that would never harm her. Olympias’ presence was powerful and unnerving. She was known to be supremely ambitious and ruthless, not fitting the image of a traditional Macedonian queen. Her enemies at court tended to suffer misfortunes.

It is known in the ancient annals that Olympias was struck in a dream by a lightning bolt, causing a sacred fire that spread to all corners of the earth before petering out abruptly. From that point on, it was believed that the king’s son had a significant tie to exalted and fabled Zeus. Philip also dreamed he was putting a seal on his wife's womb, with the seal bearing the image of a roaring lion.

On the day of Alexander’s birth, Philip’s horses won at the Olympian Games, and his general Parmenion roundly defeated the Illyrian armies. The Temple of Artemis suddenly caught fire. All of these omens seemed to confirm that something about the boy was not of the regular order. Although many priests were distraught over the destruction of the temple, Philip retorted that a son born amid three great victories would always be triumphant, and that Artemis had simply come to witness the birth.

Both parents, however, had a habit of making enemies.

During his childhood, Alexander quickly noted the advantages that the recently deceased ruler of Thebes, Epaminondas, had gained by surrounding himself with philosophers and learned men. Although Alexander admired his father’s achievements as a potent and powerful ruler, he understood that Philip was partially filling the power vacuum left by this mysterious man’s death, and paid close attention. He also heard stories from Persian magnates in exile, such as Sisines, about the quality of scholars and priests in Asia, which filled him with envy and a desire to unlock the secrets of that continent.

Consequently, he courted the attention of some of the most learned men in Greece, even playing boyish tricks to do so. He also went out of his way to attract the attention of Persian envoys, asking them endless questions about the situation in their country.

He soon became best friends with Hephaestion, an optimistic and learned boy of distant relation, who would become his lifelong companion due to his marked loyalty; and Craterus, an older and more taciturn boy who served as a role model for Alexander through his sublime battlefield skills.

The talents of Hephaestion lay in personal combat and organizational skills, from which Alexander learned much. From his senior, Craterus, he learned about higher-order military matters and how to be the best of generals, something he could only partially learn from his father due to their strained relationship. Alexander understood the value of eternal friendship from the Iliad, from Pelopidas, and from much of the Pythagorean literature he studied. Hephaestion functioned as his left hand; Craterus, as his right fist.

Witnessing the alienation and chaos his quarreling parents brought to the court, he wished to build a core of men, and some women, loyal to him until the end of time: his Companions and Guardians, a group he hoped would become mythological figures inscribed into history forever.

Among others, he cultivated friendships with Ptolemy, Nearchus, Laomedon, Perdiccas, and other talents among the aristocracy. It is a testament to how truly beloved Alexander was that nearly all of these boys would become men who followed him to the peaks of the Himalayas and back. Frustratingly, however, Alexander could never prevent disputes among them all.

From boyhood, Alexander was pious and strict in his adherence to the Gods. Partly due to his strange levels of power, he never doubted they were there. He always backed up his words regarding them with deeds and never forgot a pledge made, seeking always to justify the majesty of the Primordial Ones.

He worshipped the Gods magnificently from his early youth and used incense so lavishly that one who was austere and frugal exclaimed: “Make offerings like these when you have subdued the region where such things grow.” Mindful of these words, when he subdued incense-bearing Arabia, he sent many talents' weight of perfumes to Leonidas (Plut. Alex. xxv. 4 f.), with instructions not to be too stingy thereafter in honoring the Gods, since he knew they repaid generously the gifts cheerfully offered.1

Leonidas had been approved as Alexander’s tutor and essentially became his foster father.

Despite not taking things to the extremes of his foster father, frugality was another of Alexander’s traits, following the example of Socrates and Epaminondas. Being bought or bribed horrified him. It is well known that throughout his life, Alexander shot down any attempt to win him over with money; the mere suggestion sent him into a rage.

He was driven solely by the idea of being one of the names on the door of Posterity. The more the court offered in terms of pleasures, the more Alexander supposed that less fame would be attributed to him and more credited to his father, whose relationship with him was becoming increasingly difficult.

Although Alexander was known to use his fists and was highly volatile, particularly when defending the honor of his friends or his ambition, as he came into puberty, he practiced a strict degree of moderation in erotic matters. Observing keenly how his mother leveraged her own power and did not consort out of desperation, he chose to engage in such unions carefully and never conducted himself in a way that would allow distractions in the dangerous Macedonian court to hold sway over him.

After all, even from childhood, he had enemies such as Cassander, a distant relative.

He was known to be able to quote the Iliad and many of Euripides’ plays from memory. Alexander placed a high value on culture and never dismissed its influence, nor did he consider it antagonistic to his military focus.

The heroic character he exhibited as a child is best represented in the story of him taming Bucephalas, the most famous stallion in history. Ferocious and highly strung, the horse had been brought to Pella. Every man who attempted to mount it failed.

As Philip grew frustrated and ordered the horse to be taken away, saying it was utterly wild and untamable, Alexander, who was present, said, “What a horse they are losing due to inexperience and inability to handle him with skill!”

Philip remained silent at first, but as Alexander continued to speak out and show strong emotion, Philip said, “Are you reproaching your elders as if you know more than they do, or think you can manage a horse better?”

[…]

When he saw that the horse had let go of its defiance but was still eager to run, he urged it on, now pursuing it with a bolder voice and using his heel to spur it forward. At first, those around Philip were filled with anxiety and remained silent. But when Alexander turned the horse back after completing the course, riding confidently and full of joy, all the others burst into cheers.

His father, it is said, even shed tears of joy, and when Alexander dismounted, he kissed his head and said, “My son, seek a kingdom equal to yourself, for Macedonia is too small for you.”2

The precious animal subsequently accompanied Alexander in all his conquests.

Philip believed his son was not ordinary. To that end, he considered several tutors for the boy, whose name was already the subject of rumors throughout Greece. There was Speusippus, who had succeeded Plato at his academy, among others. But Aristotle came strongly into view as the only appropriate and mature tutor.

The philosopher was installed at a regular and secret school at Mieza, where he taught not only Alexander but also much of the Macedonian aristocracy. The great mind of Greece and his pupil soon forged a bond.

Although Alexander had dabbled in the occult prior to their association, it is known that Aristotle taught him intricate doctrines and methods, including advanced matters of theurgical rite to summon the Gods:

ἔοικε δὲ Ἀλέξανδρος οὐ μόνον τὸν ἠθικὸν καὶ πολιτικὸν παραλαβεῖν λόγον, ἀλλὰ καὶ τῶν ἀπορρήτων καὶ βαθυτέρων διδασκαλιῶν, ἃς οἱ ἄνδρες ἰδίως ἀκροαματικὰς καὶ ἐποπτικὰς.

It would appear, moreover, that Alexander not only received from his master his ethical and political doctrines in instruction, but also participated in those secret and more profound teachings which philosophers designate by the special terms “acroamatic” and “epoptic,” and do not impart to many.2

Through the example of his semi-divine teacher, he observed keenly that the world was already collapsing into a lack of genuine spirituality. It was this that turned Alexander’s mind toward establishing a true Empire of the Gods.

Although he admired Persia deeply, he also recognized that the manner of Persian religion since the time of Darius the Great had increasingly become devoid of quality and was taking a perverse orientation.

CHAERONEA AND THE DEFEAT OF THEBES

The seventeen-year-old Alexander accompanied his father to fight against the Maedi tribe, after which he became the left-wing commander of Philip’s royal cavalry. He soon marched to Chaeronea with his father to face the threat of Athens, Corinth, and Thebes, alongside a dozen other Greek cities that had assembled to destroy Macedon.

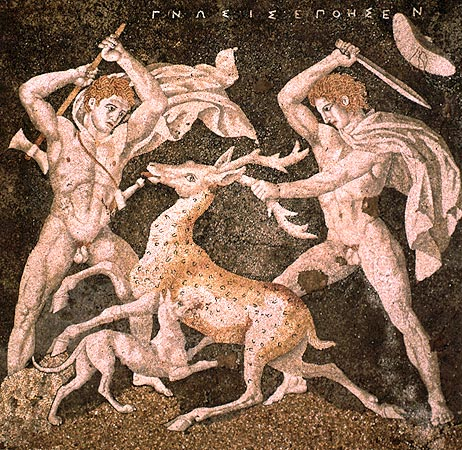

While his father led the direct and grueling assault against the Athenian infantry, Alexander employed ingenious encirclement tactics to smash into the other side with his portion of the phalanx and directly confronted the Sacred Band of Thebes, a group he had often idolized in the literature he read compulsively as a child.

THE DISPUTE WITH PHILIP

After the battle, however, it appears Philip, who was always in two minds, felt insecure about the successes of his son, who in his estimation seemed to be moving too fast. He was already battling Olympias for control of the court and had had enough of her scheming. Snubbing her, he took the opportunity to marry Cleopatra, the niece of Olympias.

At the announcement of this, Attalus, Cleopatra’s uncle, declared he hoped a “true heir” would come along, which caused Alexander to throw a chalice at him. Father and son came to blows. Olympias and Alexander soon left for Epirus itself.

This brought great frustration. Alexander ordered his mother never to interfere in politics, and it seemed as if his own father held him in suspicion. Never one to whine, he continued to wage battle to enlarge the borders of Macedon, fighting off Illyrian tribes at the court of the Illyrian king.

Philip was assassinated by an individual outraged at being violated by Attalus. The important figures of the kingdom immediately pronounced Alexander King of Macedon. Greece and Thrace almost completely erupted in rebellion. The young king set about correcting this state of affairs at once, setting off with his father’s most capable general, Parmenion.

He went to Athens and subjugated it swiftly, despite the demands of Democritus to assassinate the young king. Here, Alexander’s infamous encounter with Diogenes the philosopher occurred.

Alexander then turned his attention to the Thracians, whom he destroyed at the Battle of the Carts by capturing the walled island of Peuce. This battle alone demonstrates Alexander’s exceptional skill in turning around a near-suicidal situation, and may be too long to recount fully in this excerpt.

Once again, the Athenians and Thebans rebelled. Alexander decided to utterly destroy Thebes.

In spite of his brutal acts at times, one attribute of Alexander becomes obvious. During the siege of Thebes, Timocleia, a noblewoman, was raped by a Thracian commander (expressly against Alexander’s orders). Afterwards, the commander asked her where her valuables were; while he was peering over a well, she kicked him into it and slowly stoned him to death.

When brought before Alexander, he said she had accomplished swiftly what he would have done himself. And despite quickly learning that Timocleia was the sister of his most hated enemy at Chaeronea, he granted her and her children complete civic freedom and a funded life on the Greek purse.

During this time, a variety of threats began to appear from Persia; traditional signs of impending conquest. A large army had been spotted arriving from Asia Minor, with brothers of Shah Darius III in attendance. Alexander was elected head of the Greek empire.

He anointed the grave of Achilles, his highest hero, with oil, and ran around it with his Companions.

ASIA MINOR

Alexander met the Persian armies at the Granicus River. Parmenion advised Alexander to instruct the troops not to cross the river, which Alexander viewed as cowardice and unbecoming of a king. Some of the troops on his right flank crossed the river anyway, despite perilous stormy weather. The elite guard of the Persians, including commanders Arsames, Spithridates, and Arsites, met them in response, triggering a trap set by Alexander.

Though the Greeks surrounded the Persians, the battle, fought in increasingly muddy and desperate conditions, posed a serious danger to Alexander’s companions. Isolated on a riverbank and wearing highly ostentatious armor, Alexander was nearly beheaded by the Persian noble Rhoesaces and the Shah’s son-in-law, Mithridates. He was saved by his friend Cleitus, who intervened just in time.

Meanwhile, Parmenion, commanding the phalanx on the left flank, fought against the Bactrian and Medean cavalry. This contingent, under Rheomithres, panicked upon seeing the Persian nobles fall and fled the battlefield. Alexander had won his first major engagement.

ISSUS AND THE LEVANT

EGYPTIAN CAMPAIGN

Alexander was hailed as a hero by the Egyptians, who had despised Persian hegemony since Shah Cambyses conquered the land. Typically critical of foreign rulers, the Egyptians nonetheless held Alexander in high regard, even crowning him in the Temple of Ptah.

Though his time in Egypt was brief, Alexander undertook ambitious building projects, restoring many temples such as the Sacred Barge complex at the Temple of Luxor. He also reformed the Persian taxation system to align with Greek norms, alleviating many debts and preventing the frequent famines that plagued the region.

He visited the oracle of Amon-Ra (a distinct deity from the Amon to be mentioned later) at the Siwa Oasis. The oracle proclaimed him a son of the highest Amon (Zeus). From then on, Alexander appeared on coinage with the ram’s horns and began to be regarded as divine. The pronouncements of the Egyptian priesthood held great weight in those days.

GAUGAMELA AND THE CONQUEST OF BABYLON

Gaugamela was the most important battle of the entire campaign. Before the battle, Alexander performed rites to the Goddess Nemesis, the Erinyes, and the God Alastor, calling upon their help.

He knew Darius had assembled a massive force made up of the empire’s most brutal and efficient units, including the elite Immortals and many war elephants. Yet Alexander calmly slept for up to twelve hours before the battle, confident in his strategy.

Darius, flanked by Bessus, the governor of Bactria, attempted to outflank Alexander with a force ten times the size of the Macedonian contingent. Believing Alexander to be overextended and vulnerable, Darius ordered a central charge of Agrinian missile men, phalanxes, chariots, and elephants, expecting an easy victory. But the Greeks cleverly created openings in their lines to allow the chariots through and disoriented the elephants. Mazaeus, on the Persian right, charged at Parmenion, who, though overwhelmed, held firm.

The Greek phalanxes and missile throwers soon targeted Darius directly, provoking him into a panic. Alexander then pivoted left with his Companions, determined to capture Darius. Brutal hand-to-hand combat followed, during which Alexander’s horse was killed. Though Darius entered the battle, his advisors and poisoners convinced him to flee.

Many in Babylon saw Alexander as a liberator. Babylonian sources such as BCHP 4 and the Babylonian Astronomical Diaries refer to him as “King of the World” and mention an order he gave prohibiting his troops from entering civilian homes, demonstrating his sanctity and respect for life. Recognizing Mazaeus as the only Persian commander who did not flee, Alexander appointed him satrap of Babylonia under his authority, the first Persian to hold such a position in his new empire.

Alexander deeply respected the antiquity of Mesopotamian civilization. Historical records note that he surrounded himself with Babylonian priests, a move misunderstood by many of his contemporaries. As High Priest Hoodedcobra relates, they tested Alexander, asking if he could see a demon in the room, and he passed the test effortlessly.

Upon entering Babylon, he performed rites to Marduk (Bel), the chief Babylonian god, and ordered the reconstruction of Marduk’s great temple, the Esagila, which Xerxes had destroyed.

Some suggest that the identity of Serapis, the Hellenized form of Osiris later popular across Egypt and the Roman world, may have originated in Babylon during Alexander’s initiation into the local mysteries.

At the time, a Jewish community in Babylon, still obscure but rising, sought an audience with Alexander. They tried to proclaim him the “New Cyrus” and urged him to destroy idols, following Cyrus’s example with Nabonidus. Alexander, seeing through their aims, rejected their appeals entirely.

With more pressing matters than appeasing a deviant Middle Eastern tribe, Alexander paid them little heed. In response, later Jewish texts like the Talmud and Midrash constructed flattering fictions, portraying Alexander bowing to the Jewish high priest. They even began naming children “Sender” to curry favor. However, Alexander demanded their cultural Hellenization and imposed Greek taxation, an act Jews later recorded as a catastrophe. Ultimately, they defied his demands.

THE KING OF PERSIA

After toppling Darius III, Alexander inherited the vast Achaemenid administrative system. Rather than dismantle it, he retained much of the Persian satrapy (provincial) structure. In many regions, he confirmed Persian officials who submitted to him, a pragmatic move that ensured continuity and local support.

Alexander also adopted Persian court protocol where it served his aims. He styled himself as the Achaemenids’ successor, taking titles such as “King of Asia” and possibly “King of Kings.” He maintained a royal chancellery that issued decrees in imperial languages and upheld ceremonial traditions expected of a Persian monarch. In doing so, he signaled to Persian nobles and subjects that he respected their heritage and considered himself a legitimate heir to their throne.

These policies were controversial among his Macedonian Companions, who resented his Persian stylings and accused him of acting like a god. But Alexander envisioned a global empire governed by a titanic spiritual and military elite, an ideal understood by few besides Hephaestion.

In governance, Alexander refrained from looting temples for revenue, a sign of his reverence for the gods. When his troops sought to plunder the shrine of Zeus in Babylon or other rich temples, he forbade it. His respect extended to Persian fire altars as well; no records indicate he violated them. Later, Ptolemy, ruling Egypt, even incorporated Zoroastrian priests into his court, continuing a practice begun by Alexander.

He also integrated many Persian nobles into his administration. Some were retained as governors, while others joined his court and military. Notably, Oxyartes (father of Roxana, Alexander’s wife) and Darius’s brother Oxathres became part of his inner circle. Persian nobles and their sons served as officers, diplomats, and royal pages. Alexander even ordered the training of 30,000 Persian boys called the Epigoni (“Successors”) in Macedonian military methods, according to Arrian.

One important reform was the introduction of a common currency. While the Persian kings minted gold darics and silver sigloi, Alexander replaced these with gold staters and silver tetradrachms based on the Attic standard. Vast hoards of bullion seized from Persian treasuries, an estimated 180,000 talents of gold and silver, were melted down and re-coined. This monetized the Persian economy and strengthened imperial unity.

Beyond warfare, Alexander invested in administration and construction. Like the Achaemenids before him, he repaired roads, maintained the Royal Road network, and improved cities. After arriving in Babylon, he ordered the rebuilding of the Temple of Bel and other shrines destroyed by Xerxes decades earlier.

INDIA AND THE CAPTURE OF HERACLES’ AORNOS

The siege of Aornos Rock was a remarkable feat of military ingenuity and sheer determination by Alexander the Great and his general, Ptolemy. Confronted by a daunting fortress positioned atop a steep and seemingly impregnable mountain named Elum Ghar, and across from it, another elevated peak, Alexander resolved to achieve what even the legendary Heracles could not. Historians depict Alexander as meticulously strategic, initially relying on local guides to navigate the difficult terrain and identify tactical vulnerabilities. According to Arrian, Alexander systematically constructed extensive ramps and earthworks, bridging deep ravines and steadily moving siege engines upward despite relentless resistance from the defenders.

His persistence was on full display, including his direct involvement in inspiring his exhausted troops. The king supervised construction efforts day and night, continuously urging his soldiers forward, even in the face of terror due to the formidable landscape and entrenched resistance. Arrian further reinforces this account, noting the careful coordination and discipline required to maintain morale and logistics under exceptionally challenging conditions. Alexander's army slowly reduced the defenders' options, using tactics such as a feint with flames to draw the enemy out into battle for two days, inching ever closer to their heavily fortified positions.

After successfully completing the earthworks and siege ramps, he led a bold and aggressive attack directly against the fortress. Faced with imminent defeat, the demoralized defenders abandoned their posts and fled, enabling Alexander’s forces to triumphantly occupy the summit. Plutarch highlights this victory as emblematic of his superlative ambition: conquering a fortress reputed to be invincible and thereby achieving enduring fame. Aornos demonstrated Alexander’s tactical genius and unparalleled perseverance.

MALLI AND THE RETURN TO PERSIA

Alexander nearly met his end in the dangerous maneuvers near the Hydaspes River. He was gravely wounded during his campaign against the Malli (Mallian) people, in what is now the vicinity of Multan in modern-day Pakistan. At the time, this region was part of the broader Indian subcontinent. During the siege of a Mallian fortress in 326 BCE, marked by extremely bloody, hand-to-hand, street-by-street conflict, Alexander personally led the assault on the walls, was struck by an arrow, and nearly died from his injuries before being rescued by his men.

Peucestas is often singled out for his bravery, having fought off many warriors to get the king to safety and defending the severely wounded Alexander with the “sacred shield” (a trophy taken from the Temple of Athena at Troy). Other companions, such as Leonnatus and the soldier Abreas, also played crucial roles in keeping enemy fire at bay and helping Alexander until the rest of the Macedonian troops broke through to rescue him.

His soldiers, exhausted from endless fighting, could march no more.

HEPHAESTION’S DEATH

After completing his campaign in the Indian subcontinent, Alexander led his army back westward, traversing the treacherous Gedrosian Desert. The crossing was marked by harsh conditions, crippling heat, and severe shortages of food and water, resulting in substantial losses among his troops. Despite these hardships, Alexander’s overarching goal remained the continued stabilization of his empire, which he had expanded dramatically through conquest. His resolve to return to Persia stemmed in part from the need to restore control over restive satraps and governors who had begun to abuse their positions during his extended absence.

Once he arrived in Persia, Alexander made a notable effort to integrate the Persian aristocracy and customs more fully into his dominion. His famous mass marriage ceremony at Susa illustrated this policy: he and many of his officers married Persian noblewomen in a grand affair intended to symbolically unite Greek and Persian cultures. Alexander believed that by merging the traditions of both peoples, he could lay a firmer foundation for the lasting governance of his vast empire. Some of his Macedonian officers remained wary of this policy, seeing it as an undesirable shift away from their cherished homeland values.

In an attempt to foster unity, Alexander also adopted certain elements of Persian court protocol, including the wearing of Persian clothing and the practice of proskynesis; bowing or prostrating before the king. This move caused friction with many of his Macedonian companions, who were accustomed to treating their king as a “first among equals” rather than a distant monarch. Nonetheless, Alexander persisted, believing that his new approach was a pragmatic response to the challenge of ruling so vast and diverse a territory.

Meanwhile, Alexander took steps to address both corruption and inefficiency among his provincial administrators. Returning satraps and military officials faced stringent reviews of their governance. Some were removed from power or severely punished for mismanagement and the exploitation of local populations. By stabilizing the governmental structure in Persia, Alexander hoped to ensure that resources and tribute continued to flow to the royal treasury, key to maintaining his huge standing army and ambitious building projects.

Despite considerable administrative demands, Alexander did not remain static in one place. He journeyed extensively through the provinces, dispensing justice, inspecting garrisons, and establishing new settlements when needed. Everywhere he went, he reinforced his image as a ruler who combined Greek and Persian ideals: a formidable conqueror, a patron of cultural fusion, and an absolute monarch committed to sustaining order.

The ambitious, beautiful, and ruthless Roxana from Bactria, a woman dancer remarked to be much like Olympias, soon became the wife of Alexander and later bore him an heir, also named Alexander. However, Alexander also married Stateira, the daughter of Darius, and arranged the marriages of his Companions to elite Persian women in what became known as the Marriages of Susa.

During this period, Hephaestion, Alexander’s closest friend, was promoted to chiliarch, an office that placed him second only to Alexander in the command structure. Hephaestion played a critical role in maintaining the loyalty of the troops, managing administrative affairs, and acting as a trusted advisor in matters of state. He enjoyed considerable influence in court circles, further symbolizing the unity of old Macedonian allegiances with the evolving, Persian-influenced royal court.

Hephaestion fell gravely ill in Ecbatana in 324 BCE and died not long afterward. Alexander was said to be inconsolable at the loss of his dearest companion. Reports describe how he rode about in a chariot in mirror image of Achilles, lay hopelessly alone, forbade music, decreed an extensive period of mourning throughout the empire, and even staged lavish funeral rites worthy of a hero, after the oracle of Zeus Ammon affirmed his request to elevate Hephaestion to such a status. His death left an immense void for Alexander, foreshadowing the final months of the Macedonian king’s earthly life, which would also end abruptly in Babylon the following year.

THE END

Alexander began to associate more and more with the Babylonian priesthood. He left Ecbatana and made his way toward Babylon, the city he intended to use as his administrative capital. Although still in mourning, he continued issuing orders to strengthen governance in the far-flung provinces, aiming to ensure that the satraps and local rulers understood the permanence of Macedonian power.

During these final months, Alexander turned his attention to unfinished projects and the future expansion of his domain. One of his most concrete plans was a campaign to subdue Arabia, which he believed would complete the encirclement of the Persian Gulf and extend Macedonian influence along strategic trade routes. He ordered the construction of a fleet and the recruitment of supplies, shipbuilders, and navigators, reflecting the grand ambition that still drove him despite the personal tragedies he had endured.

In Babylon, Alexander renewed efforts to integrate Hellenes and Persians into a functioning imperial administration. He arranged for the mass demobilization of some veterans to return home, partially as a reward for their years of service and partially to reduce the financial burden on the treasury. However, he also replenished his army with fresh troops from the eastern satrapies, maintaining the core of a formidable fighting force for future expeditions. Alexander remained firmly focused on solidifying the foundation of his empire.

Even as Alexander planned new ventures, a series of troubling omens and unsettling portents seemed to cast a shadow over his final days.

Alexander entertained foreign envoys from as far as Carthage and Italy, reinforcing his reputation as a world conqueror open to diplomatic exchange. Simultaneously, he convened councils with top officers like Perdiccas, Ptolemy, and Seleucus to refine his plans for both immediate governance and the upcoming Arabian campaign. His ability to maintain a frenetic schedule while supervising administrative reforms underscored his indefatigable energy, a quality that had propelled his conquests from Greece to India.

Suddenly, however, Alexander fell seriously ill after a banquet held by his Companion Medius. Over roughly two weeks, his condition worsened, marked by fever and debilitating pain. Classical sources (Arrian, Plutarch, Diodorus, and others) differ on the exact cause, offering possibilities ranging from overindulgence in drink to poison plots or simple malaria contracted in the marshy environs of Babylon. Whatever the true source, his entourage grew increasingly anxious, for no physician’s efforts seemed to stem the decline of the thirty-two-year-old king whose vigor had once seemed inexhaustible.

As death approached, Alexander reportedly lost the ability to speak coherently, but remained conscious enough to acknowledge his soldiers by nodding or gesturing in farewell as they filed past his bedside. He was asked to whom he would leave his empire, and tradition holds that he murmured a cryptic response: “To the strongest.”

On June 11, 323 BCE, Alexander the Great left the world in Babylon. His absence ended one of the most extraordinary chapters in history ever written.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1History of Alexander, Quintus Curtius

2Life of Alexander, Plutarch

Anabasis of Alexander, Arrian

Biblioteca Historica, Diodorus

Alexander Romance

With Alexander in India and Central Asia, Moving East and Back to West, various, edited by Claudia Antonetti, Paolo Biagi

CREDIT:

[TG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe