Boccaccio

Great Poet

The great poet and writer of Italy, Giovanni Boccaccio, existed in a transitional period that marked the Sun setting on the Age of Ignorance. He became known to all as one of the Three Crowns of Italian literature, alongside Dante and Petrarch. All three writers contributed to the dawn of the Renaissance.

In contrast to his role model Dante and close friend Petrarch whose lukewarm loyalty to Christianity mixed itself with an appreciation of the Classical world, a strong theme of anti-clericalism emerged in Boccaccio’s works, being that he wrote amidst a turbulent 14th-century backdrop lynchpinned by the devastation of the middle of the century that primed his invectives and skeptical themes.

The Catholic Church, though universally dominant in spiritual life, was marred by widespread corruption and political entanglements. Boccaccio became close to the Papacy and even served as a secretary for the Pope but privately became increasingly pessimistic about the nature of the religion during the Black Death. Preceding Plethon’s resurrection of true religion, he had multiple crises of faith and approached the Gods from the perspective of ignorance.

THE YOUNG POET

Boccaccio was born in a town near Certaldo where his family originated. He was the son of a Florentine business magnate named Boccaccino who held several important positions and offices. Boccaccio's stepmother was called Margherita de' Mardoli.

Due to the high office of his father, he completed his first studies at the school of Giovanni Mazzuoli da Strad. At leisure to indulge himself in the literary circles of his time, he was quickly strongly influenced by Dante’s works.

Being a devout Christian at this point, Boccaccio’s major interest was in the study of Theological Law, quite preceding his creative endeavors. However, Boccaccino wanted his son to become a merchant, according to the family tradition. After having him do a short apprenticeship in Florence, in 1327 he decided to take his young son with him to Naples, a city where he worked as a stockbroker for the noble Bardi family.

He demanded that he would go to the Studium (the present-day University of Naples), a venue where he studied canon law for the next six years. He also pursued his interest in scientific and literary studies.

On the morning of Holy Saturday, March 30, 1331, when the author was seventeen years old, he met a Neapolitan lady with whom he fell passionately in love. The encounter described in his work Filocolo, whose immortalization he gave as Fiammetta ("Little Flame") and whom he courted relentlessly with songs and sonnets.

Fiammetta opened the doors of the court to Boccaccio and, more importantly, encouraged his budding literary career. Partially due to her influence, Boccaccio wrote his juvenile novels and poems, from Filocolo to Filostrato, the Teseida ,the Ameto , the Amorous Vision, and the Elegy for the Madonna Fiammetta. It is known that it was her who ended the relationship between the two due to factors of class, and that the breakup caused Boccaccio deep pain.

NEOPOLITAN WORKS

Boccaccio wrote many works during this time period, many inspired by the Classics. His letters show an extreme knowledge of such matters, invoking the Goddess Pallas upon hearing of a violent and strong feud among families.

The Teseida is an epic poem in octaves which recalls the deeds of Theseus who fights against Thebes and the Amazons, drawing on thee Cycle of Thebes. The Philostratus concerns the hero of Troy, Troilus, who despairs after his love Chryseis falls in love with the Greek hero Diomedes.

Diana’s Hunt and Comedy of the Florentine Nymphs concern virtue. In the latter work, seven virtuous nymphs of Venus recount to the wild man Ameto their love affairs with men who represent the opposite quality, with Lia, the object of Ameto’s affections, representing faith and civilization. She throws him into a clear spring through which he is purified and pursues cultivation.

Boccaccio’s writing style was revolutionary and represented a kind of diverse approach. He wrote variously in vulgar registers paralleling the speech of peasants, educated elite Tuscan of a high register and Latin itself as the work demanded. His Boccaccio's style boldly combined genres, allowing comedy to coexist with tragedy, satire with seriousness, and eroticism with morality, creating a rich, multidimensional narrative style unprecedented in medieval literature. He varied from epic poetry to tercet compositions to novels, innovating in structural approaches to poetry.

THE PLAGUE

He turned back to Florence due to bankruptcy issues of his father, then went to Ravenna and Forlì, where he received patronage under the great Francesco II Ordelaffi.

In 1348 he returned to Florence, where he witnessed the plague described in the Decameron. The Plague caused the death of many of his friends and relatives, including both his father and stepmother by 1349, even though his father led a valiant effort as minister of supply to alleviate the total disaster. Depressed and despondent, Boccaccio settled permanently in Florence to look after what remained of his father's estate.

Although Boccaccio had gained some recognition in Naples, on the city on the Arno river close to his origin, he became appreciated for his literary approach. The Decameron was composed during the first stage of his stay in Florence, between 1349 and 1351. It was ironically the fame of the Decameron that elevated Boccaccio to higher offices such as ambassador to the Lords of Romagna and ambassador of Florence to the Papal court in France, even serving in Avignon directly, an area that he had visited often prior to the writing of the book.

BACKGROUND

The papacy’s residency in Avignon (1309–1377) under French influence epitomized the Church’s worldliness. Pope Clement VI, reigning during the Black Death of 1348, kept a court notorious for luxury, open simony (the selling of church offices and forgiveness), and flouted celibacy. Such scandals made the clergy a common scandal and a running joke in popular perception.

At the same time, Christendom was shaken by the Black Death, which killed a third or more of the population of Europe, absolutely devastating Italy. The poet’s vivid introduction to The Decameron describes how neither human science nor devout prayer could halt the plague’s advance. “Humble supplications to God” and public processions proved utterly useless against the pestilence.

Traditional religious explanations faltered, fostering an atmosphere of disillusionment. People saw priests dying or abandoning their flocks, and funeral rites reduced to perfunctory burials by a few hurried clergy.

Although Boccaccio was indeed a loyal Christian for the first three decades of his life, the witnessing of the Great Plague sent him into dark corners questioning the nature of Christianity. Traditional religious explanations faltered, fostering an atmosphere of disillusionment. People saw priests dying or abandoning their flocks, and funeral rites reduced to perfunctory burials by a few hurried clergy

Even as most Italians remained sincerely Christian, many became openly critical of Church institutions and personnel. As one modern scholar notes, Boccaccio’s work reflects a society “increasingly oriented towards a detached agnosticism,” even while core tenets of faith or the personal God–conscience relationship are not directly condemned.

DECAMERON

The Decameron is a collection of 100 tales told by ten young Florentines sheltering from the plague. The work is his masterpiece of social realism and humanistic ethos. Throughout the Decameron, Boccaccio wove pointed critiques of clergy and Church practices, ranging from overt satire to subtle irony.

During the Black Death in Italy, seven young women and three young men flee plague-ravaged Florence, seeking refuge in an isolated countryside villa near Fiesole. To pass their evenings pleasantly during a two-week stay, they decide that each member of their group will tell one story per night, except for days reserved for chores and holy days when storytelling is paused. Over the course of ten evenings of storytelling within these two weeks, they ultimately share a total of one hundred tales.

Each participant takes a turn serving as the King or Queen of their company for a day. The appointed monarch selects the theme around which all stories told that day must revolve. Among the chosen topics are stories illustrating the power of fortune, demonstrations of human willpower, love stories ending happily, tragic love tales, clever replies saving their speakers, examples of virtue, and tales about tricks women play on men or general tricks people play on one another. Additionally, one storyteller, Dioneo, known for his wit, enjoys the unique privilege of choosing any topic he desires, typically speaking last each day.

Many tales serve as anticlerical parodies, exposing clergy who are greedy, lustful, or foolish, and thus holding them up to ridicule. At the same time, a few stories gently question aspects of Christian doctrine or exclusive truth-claims, suggesting a religious skepticism unusual for his era.

From the very first day of storytelling, Boccaccio sets an anticlerical tone. Day I, Novella 1 recounts the saga of Ser Ciappelletto (Cepparello), “a walking catalogue of sin” who falls deathly ill while lodging with two Florentine moneylenders. Knowing Ciappelletto’s wicked life, his hosts despair of finding a priest who will absolve him. The dying man calls a friar and delivers an absurdly false confession, claiming to be a paragon of virtue that the naive friar believes.

Upon Ciappelletto’s death, the friar praises him so fervently that this notorious sinner is revered as a saint and his tomb becomes a shrine. Boccaccio exposes the flawed sacrament of confession and the process of canonization: the “wickedest man” becomes a popular saint simply because the friar is too pious (or foolish) to detect a lie. Christianity is depicted as so corrupt or gullible that it exalts vice as virtue.

In Day I, Novella 2, anticlerical critique continues in a more ironic vein. A wealthy Christian merchant, Jehannot, urges his Jewish friend Abraham to convert to Christianity. Abraham skeptically travels to Rome to observe the papal court, where he finds clergy wholly depraved – “nothing but debauchery” and vice among the cardinals and priests. Paradoxically, Abraham converts to Christianity anyway, reasoning that a religion which still grows despite its corrupt leaders must have divine truth behind it.

Many other Decameron tales unabashedly lampoon the sexual hypocrisy and greed of the clergy. A classic example of farcical anticlerical comedy is Day III, Novella 1, the tale of Masetto da Lamporecchio, a handsome peasant who pretends to be a deaf-mute to gain employment as a gardener at a convent. The young nuns, believing Masetto cannot speak, proceed to seduce him one by one, each nun taking her turn with the mute gardener until “he eventually succeeds in making love to them all” and is in fact invited to stay on permanently as their secret lover and unofficial “indispensable” member of the convent.

The story incisively attacks the ideal of cloistered chastity. Behind closed convent walls, the so-called brides of Christ are as passionate as any secular women, only constrained by lack of access to men. The inversion of roles (a supposedly mute man who actually pleasures an entire convent) and the happy outcome (Masetto thrives, and the nuns learn to arrange their illicit affairs more discreetly) amount to a “desecrating parody” of saintly legends.

By showing churchwomen as fully human and fallible, Boccaccio undermined the pretensions of moral superiority among the Church. Another incisive tale is Day IX, Novella 2, where a bungling abbess and a novice nun are each engaged in illicit trysts. The young nun is caught with a lover, yet when the abbess rushes to discipline her, she accidentally wears the priest’s pants on her head in place of her veil, revealing her own misconduct.

Boccaccio’s contempt for empty moral posturing is evident. He implies that for many in religious life, the only sin was in getting caught.

Fraudulent miracle-mongering and greed for donations which were common critiques of mendicant friars in the 14th century also receive comic treatment.

For instance, Friar Cipolla in Day VI, Novella 10 is a wandering friar who each year visits the town of Certaldo (Boccaccio’s own hometown) to collect alms from the gullible. He promises the villagers a rare spectacle that he will display a feather from the Archangel Gabriel, a holy relic, in exchange for generous offerings. Two local pranksters secretly replace the feather with a heap of coal. When Cipolla unveils his reliquary and finds only charcoal, he improvises in manipulation, claiming the coals are themselves sacred relics, the very coals that roasted St. Lawrence, miraculously transported to him.

The crowd, far from turning on him, accepts this explanation enthusiastically, and Cipolla cheerfully collects his donations. Boccaccio’s friars, in general, are drawn from the stock figure of the comic mendicant: ignorant but silver-tongued preachers, gluttonous and avaricious, who exploit popular faith.

The Decameron holds up a mirror to a Church that, in Boccaccio’s view, had strayed far from religion. Perhaps the most revealing contention attached to this is the tale of Day I, Novella 3, often called the parable of the Three Rings. In this tale, the great Sultan Saladin asks a wise Jew, Melchizedek, to identify which of the three Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) is true. Melchizedek responds with a story: a father had an invaluable ring and, wanting to honor all three of his sons, he secretly commissioned two exact copies and gave each son a ring, telling each that his was the true one. After the father’s death, the sons quarrel, each claiming to have the authentic ring, but an expert cannot discern the real one. All three “appear” genuine, and thus the true heir cannot be determined. On this I say no more…

FRIEND OF PETRARCH

From 1350 onwards a deep relationship was born between Boccaccio and Petrarch, which would be borne out in the meetings of the following years. Boccaccio's "conversion" to nascent humanism gradually took place. From his early youth in Naples, Boccaccio had come into contact with rich libraries, among which that of the monastery of Montecassino possessed multiple codices by authors who were almost unknown in the rest of Western Europe were kept. Among these were Apuleius, Ovid , Martial and Varro, many of whose works had long been banned for ‘vulgarity’.

The revival of classical antiquity, fundamental to the Renaissance, owed a lot to Giovanni Boccaccio's spirited defense of classical literature. Boccaccio actively challenged certain clerical intellectuals who sought to restrict access to classical sources, fearing moral corruption among Christian readers due to the pagan ideas they contained.

In this, he conscripted the efforts of Leonzio Pilato who was a very disreputable monk, but Boccaccio patronized his efforts to learn Greek and to translate the Iliad and Odyssey for the first time. Believing that antiquity still held valuable lessons, Boccaccio in this exchange produced the Genealogy of the Pagan Gods (Genealogia deorum gentilium), a comprehensive defense of classical mythological studies. Completed in its first edition by 1360, this influential text became a principal reference on classical mythology for over four centuries.

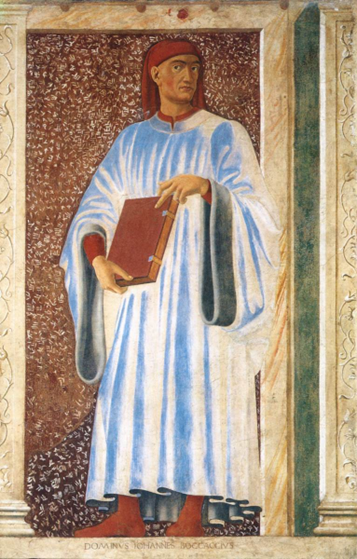

near contemporary detail from a cycle of frescoes in the Ancient Seat of the Art of Judges and Notaries (Florence)

The inception of the Genealogia also stemmed significantly from Boccaccio's friendship and intellectual exchanges with Petrarch. After their initial fruitful encounter, Boccaccio considered Petrarch his teacher and magister, and Petrarch encouraged him to pursue deeper studies into classical Greek and Latin literature. Their dialogues were notably spirited when they met again in Padua in 1351 since Boccaccio officially invited Petrarch to accept an academic position at the University of Florence.

Petrarch declined the offer, their conversations profoundly shaped Boccaccio's scholarly direction and his dedication to promoting classical antiquity. The two continued to be friends into old age, although a revealing letter reflecting on Petrarch’s death shows Boccaccio saying Petrarch will be reunited with ‘Christ, his redeemer and savior…’

ORDAINMENT

Boccaccio was ordained in 1360 and in doing so became personally acquainted with the Popes, which gave him further access to many texts and libraries across Italy that were under strict control. It is known from his letters that he conspicuously travelled to monasteries to find everything about the history of the church in the most minute detail.

These adventures were a pretext to sate his increasing desire to approach ‘the Lord of this World’, triggered by multiple crises of faith. Boccaccio kept many of his real beliefs private and consulted the works of demonology, knowing from his study of Polybius under Pilato’s suggestions that the Daemons were not evil beings. He also investigated enemy demonological tracts that appeared during the 12th century such as the Sworn Book of Honorius.

Due to his connections within the church and extensive right of way as a diplomat, Boccaccio also became a prevalent figure in the nascent area of archeology at this time. He is known to have supervised several attempts to retrieve ancient objects in digging expeditions, and although these attempts were primitive in scope, they foreshadowed the first modern archeologist, Cyriacus of Ancona, a century later.

A major famous work was his biographies of famous women, De mulieribus claris. Boccaccio was not aware of the allegorical nature of classical mythology and he expresses incredulity at paganism, but revealingly states regardless that the golden age of Antiquity was a far better era than the present ugly and dark age, affirming the attitude of his best friend Petrarch.

Another late work, Boccaccio’s commentary on Dante’s Divine Comedy (Esposizioni sopra la Comedia, 1373), shows him engaging with Dante’s often fierce ecclesiastical critiques. Dante, a generation older, had famously condemned corrupt popes and simoniacal priests in his Inferno. When Boccaccio lectured on Dante in Florence, he discussed these passages. Although Boccaccio’s own commentary survives only in part, it’s recorded that he explained Dante’s moral philosophy.

There is also an interesting letter of Boccaccio’s Epistle XXII to Mainardo de’ Cavalcanti. In this letter (written in the 1360s), Boccaccio responds to charges that The Decameron was immoral or anti-religious. He defends his intentions, arguing that he depicted clergy realistically, not out of hatred of religion, but to reveal the truth.

LEGACY

Secularly, he quickly became recognized as one of the greatest Italian authors and a Father of the Renaissance. For many years, the Decameron was the most popular work in all of Europe beside the traditional Alexander Romances and continued to be reproduced strongly after the advent of the printing press. The spirited, florid, humorous and often highly erotic nature of his works influenced many authors in Italy in the next two centuries.

Although not as well-read or translated as Dante now, Boccaccio left a lasting legacy on English and French literature by being the inspiration for Geoffrey Chaucer’s work the Canterbury Tales and the religiously tolerant Marguerite de Navarre’s Heptaméron, which both reinterpret parts of the Decameron. Through this, he influenced Bacon, Shakespeare and Moliere to a large extent. His invectives against the Church also influenced Nietzsche’s critique of Christianity.

Although the corruption of the Church in his time more or less allowed for Boccaccio to act as he wished, the Church’s attitude to Boccaccio soured in the preceding centuries. In 1497, the lunatic zealot Savonarola included copies of Decameron in his “bonfire of the vanities” in Florence, condemning it as a morally corrupt book. During the Counter-Reformation, the Church took stronger action as the Decameron was placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Prohibited Books) in 1559. To be read in Catholic countries, it had to be expurgated, hence entire tales or at least offensive passages were cut or “corrected” by ecclesiastical censors.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Epistolae, Boccaccio

Decameron, Boccaccio

Diana’s Hunt, Boccaccio

Teseida, Boccaccio

Comedy of the Florentine Nymphs, Boccaccio

Introduction to Decameron, Richard Hooker

Franciscans in the Middle Ages, Michael Robson

The Merchant Giovanni Boccaccio in Montpellier and Avignon, Giuseppe Meloni

Greek, the phantom language of the medieval West, Emanuele Coccia

Giovanni Boccaccio, Vittore Branca

La rivoluzione incompiuta: Società politica e cultura in Italia da Dante e Machiavelli, Ugo Dotti

CREDIT:

[TG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe