George Washington

President of the United States

George Washington was described by fellow Revolutionary War comrade Henry Lee as "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen".

Holding the illustrious title as the

Father of America, few names are as well known as his.

What is less well known, however, are the Hellenistic, and thus, Zevist, ideals that empowered Washington and his virtues. Many to this day falsely ascribe regular Christianity to Washington,

unknowing of the fact that this was a myth dispelled over 200 years ago, in the journal of Thomas Jefferson himself, who wrote "Gouverneur Morris had often told me that

General Washington

believed no more of that system (Christianity) than did he himself."

Indeed, Washington himself was a Mason, and this was prior to the Masonic movement's corruption and Judeo-Christianization which began in 1782 with the Congress of Wilhelmsbad and the allowance of Jews into the movement, of which they had always been banned.

In fact, Washington himself was aware of this corruption, and wrote to a friend about it the year before his death (which will be posted at this article's end). It's plain to understand why exactly Jewish powers were so eager to corrupt this movement from the inside out, and why Hitler ultimately saw fit to destroy the Masonic Lodges in Germany, given said corruption, when you consider the height from which the movement fell.

After all, the movement was once reflected by virtuous men like Washington and his contemporaries, and knowledge of this helps contextualize Washington's own Hellenistic virtues; something that was nurtured and developed amidst his trusted peers and fellow intellectuals within the movement who ultimately helped build the foundation of America. Something that one can consider as a very literal representation of a Mason, that being someone who builds.

EARLY LIFE

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, at Pope’s Creek Plantation in Westmoreland County, Virginia. He was the eldest child of Augustine Washington and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington. His father, Augustine, belonged to an established Virginia gentry family descended from English immigrants from Yorkshire who settled in the American colonies in the mid-17th century. Washington’s lineage linked him to prominent colonial families, lending him a sense of social prominence, although not excessive wealth, which shaped his early experiences and aspirations.

At age eleven, he faced the loss of his father, an event that profoundly impacted his youth. With limited formal education, his learning was derived primarily from practical experiences, tutoring, and rigorous self-study. He developed skills in mathematics, surveying, and farming, which contributed significantly to his character, imbuing him with practicality, determination, and a disciplined approach to life. Friends and family remarked upon the seriousness, integrity, and maturity that distinguished his personality from a young age. Washington was dignified and composed, exhibiting remarkable self-control even under great stress, according to contemporaries such as Thomas Jefferson.

As a teenager, Washington pursued surveying as a career. He worked under experienced professionals and eventually earning official appointments. His meticulousness, reliability, and physical endurance earned him the trust and respect of influential Virginians, notably the powerful Fairfax family. His association with Lord Fairfax opened doors to broader opportunities, allowing him to survey extensive frontier lands in the Shenandoah Valley. These experiences honed Washingtons leadership qualities, fostering his independence and deep connection to the land.

By 1753, at age 21, Washington was already demonstrating traits of leadership and ambition, shaped by his upbringing, family expectations, and early experiences. Despite his youth, he had gained significant responsibilities, including appointments in the Virginian militia and as a surveyor of frontier lands. His disciplined demeanor, seriousness of purpose, and reputation for dependability set the stage for the broader historical role he was soon to play, laying foundations for the steadfast character that defined his later leadership.

In his late teens, Washington was a devout Christian. After this point, however, it is noted in the sources that this faith began to recede, possibly triggered by his advancements in Masonry.

MILITARY LIFE

Washington's life as a leader began with his service as an officer in the French and Indian War, starting in 1753, in which the British and French Empires came into conflict over control of the Ohio River Valley region. It was this service which solidified Washington's military and political skills, with the man himself well regarded not only for his command, but for his own presence in battle, given his notable size, strength and bravery - in quantities enough that other soldiers followed him without question.

It was also this experience which gave Washington particular insights into the strengths and the weaknesses of the British military of the time. He'd been present for both victories and defeats alike, and although England denied him the honor of commission, he was still lauded by his fellow officers, and forged valuable connections he would come to call on later in life.

For the time being, Washington went on to marry, living a peaceful life in Mount Vernon as a plantation owner and planter of wheat and tobacco, alongside his wife, Martha Dandridge Custis, from whom he gained partial control of said estate. The two were, by all accounts, happy, their only lamentation being an inability to have children of their own, though still dutifully raising the children from Martha's first widowed marriage.

Washington did not, however, simply come into his lot and ignore those that served alongside him. It was upon his urging that the Governor of Virginia fulfilled the agreed land bounty promised to the volunteer militia of the French and Indian War. Despite the bureaucracy heavy nature of the time, and despite the propensity for gentlemanly conduct, it was not irregular that promises made were not always promises kept, especially towards those not of the gentry.

During his peaceful years, Washington continued to have presence in local affairs. Surprisingly, despite his status as a war hero and landowner, Washington lost to Hugh West, attorney and then King's Attorney for Fairfax County, marking the only electoral lost Washington had ever suffered.

He was, however, undeterred. Running three years later in 1758, he ultimately won soundly, even despite not being present at the time, having been occupied by the Forbes Expedition, a remaining French fort from the aforementioned war.

Even early on in his political career, Washington had already begun to become critical of British handling of the colonies. Though he led a popular, active social life at Mount Vernon, Washington never let himself be uninformed on the news of the hour. More and more, it became apparent Washington increasingly felt at odds with the Crown, given the implementation of stifling taxes, a lack of acceptable colonial representation within British parliament, and a refusal of further settlement growth as a means of protecting British trade.

Even still, Washington and Colonial leadership weren't idle warmongers, nor were necessarily they disloyal to the Crown. Some years passed. In this time, Washington lost his stepdaughter, and dutifully canceled all other business to remain loyally by his wife's side for several months. The same year, the Boston Tea Party occurred, with factions in the Colonies now in open rebellion against British taxation.

When pressure between the Colonials and the British inevitably reached boiling point in the wake of the events in Boston, Washington was initially dismayed, though nonetheless moved to join the Second Continental Congress. Though the events of the Boston Tea Party were organized by an otherwise underground, clandestine group (albeit, with popular support from later influential Revolutionary figures), the events still inevitably cascaded into the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and the Siege of Boston itself, in which actual Colonial authority was now properly entrenched.

THE FIRST GOVERNMENT

It was within the Second Continental Congress, in which delegates from the Thirteen Colonies gathered to unite in support of the now erupting Revolutionary War, that George Washington was elected commander-in-chief of the Continental forces. In his acceptance speech, Washington yet again showed his humility and character.

"I am truly sensible of the high Honor done me in this Appointment… I do not think myself equal to the Command I am honored with."

This was not him simply acting humble for appearance's sake. Meeting later Founding Father Patrick Henry, it was said Washington's eyes appeared tearful, and he asked of him:

"Remember Mr. Henry, what I now tell you: from the day I enter upon the command of the American armies, I date my fall, and the ruin of my reputation."

Even

before heading to Boston, Washington purchased several texts on commanding large armies, unwilling to rest upon his laurels and assume himself fit for the task.

Washington was, by all accounts, the obvious choice, and John Adams, another soon-to-be fellow member of the Founding Fathers, was wise to make it. Washington had more direct combat experience

than practically any other member of the Second Continental Congress. Moreover, Washington's appearance and martial presence gave him the feeling of a strong, fit leader, particularly so

because at the time, Washington was 43, making him somewhat younger than the other Congress members and thus better tasked with a potentially drawn out conflict. As fellow Founding Father

Benjamin Rush put it, "he has so much martial dignity in his deportment that you distinguish him to be a general and a soldier from among ten thousand people."

Moreover, Washington was a Virginian. Though much of the conflict had been localized to Massachusetts at this stage, electing a Virginian as martial leader was the apparent choice, given Virginia was the most populous and wealthy of the Colonies.

More still, Washington was not seen necessarily as a zealot of Colonial belief. Washington's stance on the Boston Tea Party was measured, insomuch that he spoke of his sympathies for Boston,

but did not directly condone the acts of the Sons of Liberty. Having a sober, moderate leader at the head of the Continental forces helped convince the hearts and minds of many that the choice

to go to war as a rational one, given the circumstances. As he put it himself: "Our cruel and unrelenting enemy leaves us only the choice of brave resistance, or the most

abject submission. We have, therefore, to resolve to conquer or die."

Washington, again showing the make of his character, declined a salary as commander-in-chief, asking only to be reimbursed for the personal costs of the war.

Firstly, came the liberation of Boston. Washington was warmly greeted en-route, and quickly became the symbol of the Revolutionary War. Upon arrival, he quickly weeded out incompetent officers and instilled a strict sense of discipline. This was not only for the sake of martial prowess, but rather behavior, given the nature men often exhibit during times of war. The last thing a budding revolution needed was to be easily smeared as bestial by the British.

Indeed, when Washington was finally able to take Boston back, he refused to allow his men to plunder the city, nor did he exert military authority of it, choosing to leave and place law and order in the hands of civil authorities.

The next year, upon July 4th 1776, the Declaration of Independence was drafted and subsequently signed. Though Washington himself was fighting in New York and was therefore unable to sign in person, Washington still marched several of his battalions into the city commons to hear the document read aloud in full, Washington himself reaffirming to his men the united Colonies intend to be "free and independent states." A necessary shot of morale, given a string of recent obstacles.

All this, however, marked only the beginning of the Revolutionary War, which would go on to last 8 and a half years. Washington, of course, suffered some further setbacks, but never ones so great the war effort found itself doomed, even during the low-morale winter conflicts, owing to wise defensive strategies. By the time of the Battle of Yorktown commenced, which was, for the most part, the last major battle of the War, America found itself joined against Britain by France.

It was within Yorktown that the colonial forces under Washington assured their greatest victory. Washington paid close heed to his French advisor General Rochambeau, a man well-experienced in siege warfare where Washington was not. British forces were surrounded and unable to be reinforced, subsequently surrendering precisely two months after the siege began.

Showing his class and gentlemanship, even with the British entirely at his mercy with prisoners-of-war number into the thousands, Washington held a dinner for American, French and British Officers alike, where fraternity and respect was given in equal measure. As history has moved forward, respect for one's enemies on the battlefield has increasingly become a forgotten art.

Just over two years later, Washington held his resignation as commander-in-chief, appearing in uniform and speaking with just humility, assuring a curious nation and world that the newly independent America would not fall into barbarity now not under the guidance of the British Crown.

Washington had, in this time, some years of relative peace, before his Presidency, and after his service as commander-in-chief. He had long yearned to return to Mount Vernon, to be beside his wife, and so it was, even if for a brief time. Though he had quickly gotten back into matters of domestic business, attempting to turn around the prospects of Mount Vernon's agriculture, Washington was once again called into matters of national business.

In Washington's own eyes, and by his own words, the nation was still on the verge of "anarchy and confusion." The Articles of Confederation, signed some ten years earlier during the Second Continental Congress held little power; it was weak entirely by design, particularly given the context of the War for Independence. The Colonies didn't want to sign on for another strong central power, given that was what they were attempting to escape from, and wartime urgency mattered more at the time over a robust government.

However, this was now some years on, and Washington was correct in his feeling the Articles were inevitably going to lead to a state of anarchy, given the breakout of Shay's Rebellion over, yet again, matters of taxation and debt.

Fearing a state of national lawlessness, Washington was urged to be present for the signing of a new document, one that would ratify a far stronger central government capable of ensuring as much unity and security as it could provide to the new Republic. This document, of course, came to be simply be known as the Constitution, which still stands to this day, with fewer additions in the last two centuries than what many would assume.

THE FIRST PRESIDENT

Two years later, in 1789, Washington would then ascend to the position of America's first President, having won the majority of the vote in every state, even in spite of Washington's own assumptions that many would not vote for him. Though he maintained some feelings of anxiety, having to leave Mount Vernon behind once more, especially in such a tender circumstance, Washington left all the same, and left for New York City for his inauguration.

Maintaining his everpresent humility, and being well aware of what America needed upon stepping out from underneath the British Crown, Washington denied the urges of others to be referred to as "His Highness" or "His Excellency", preferring simply to be known as "Mr. President."

Washington's focus, particularly in his first term, was creating the foundation of America's economy to come. Despite bitter feuding within his ranks, most particularly between Jefferson and Hamilton, Washington signed off on the establishment of the First Bank of the United States. In the eyes of Hamilton, it was the responsibility of the newly established Federal Government to assume and settle the various state debts accrued during the Revolutionary War and raise revenue for the new government.

Despite Washington's best efforts to encourage a truce between the two, tensions only soured further. In Washington's mind, the formation of political parties would lead only to an overly stark division within the government, preferring the notion of a strong, singular central government. However, in the scheme of history, Washington remained the one and only President to remain entirely non-partisan.

Even still, Washington did not exile anyone for engaging in factional loyalty, nor did he shut his ears to the advice of others. Throughout the entirety of his tenure, Washington heeded his advisors, allowed opposing views to his own, and was even willing to sign bills he didn't necessarily believe in himself but simply trusted in the wisdom of those around him that did.

Despite many claims to the contrary, Washington was far less hostile to Native Americans than many have come to believe. Though circumstances, in many regards, turned for the worst after his tenure as President, Washington in his time attempted land negotiations and made symbolic gestures, sharing in peace pipes and drink with particularly powerful tribal leaders, and didn't diminish the slaying of Natives as any less criminal than the slaying of whites when done needlessly.

Even on the matter of slavery, Washington held a more considerate heart than most of his time. Though he took careful measures to avoid a civil war in the newly created Republic, gradual steps were still taken to reduce American involvement in the slave trade, free slaves, and even offer free states a place in the Union.

Though Washington had grown particularly weary of the burdens of office, homesick for Mount Vernon, and increasingly ill in health, he still ultimately chose to run for a second term, owing to the pleading of his trusted associates, with Jefferson and Hamilton even willing to put their feud aside to an extent to see it happen. In 1793, Washington was unanimously elected for his second term.

Washington continued to run the nation with the wisdom shown during his first run, opting to keep America neutral across erupting global conflicts (particularly the French Revolutionary War), and maintaining a sense of aristocracy within the American political class. Despite not even wanting a second term, the evolving American press criticized him regardless, and unfairly, further pushing the nation into a feeling of partisanship which would ultimately define much of the nation's future.

Weary of office life, ailing health and a barrage of personal attacks, Washington opted not to run for a third time, setting a sort of precedent for future presidents which eventually, in turn, became the 22nd Amendment. In the end, Washington's farewell speech held many of the hallmarks of humility had maintained since the beginning, stating that though he never intended to act with intentional error, that he was sensibly aware of his own personal defects and prayed that whatever shortcomings he did have would never cause America strife, though with the hope he'd be remembered for the upright zeal in which he served, with whatever mistakes he did make consigned for oblivion.

Washington returned home to Mount Vernon once more, though, despite his weariness and prior yearning to return home to be with his wife, he grew restless yet again. Against the backdrop of tensions with France rising, Washington returned to leadership, serving as commanding general of the now President John Adam's army, all the way until his death 17 months later.

As the nation mourned, Hamilton, one of his closest friends and allies, said it best, when he said that "if virtue can secure happiness in another world, he is happy."

Within his will, Washington took the surprising act of freeing every last one of his slaves, perhaps intending it to lead as an example to America's remaining slaveholders.

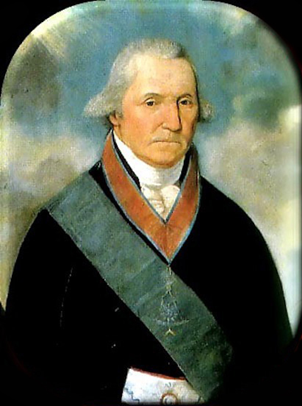

WASHINGTON THE MASON

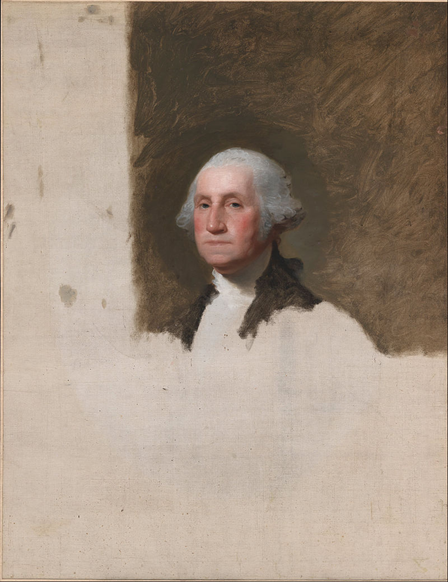

George Washington took his first step in Freemasonry on November 4, 1752, in Fredericksburg Lodge. He was passed to the degree of Fellowcraft on March 3, 1753, and raised to the sublime degree of Master Mason on August 4, 1753.

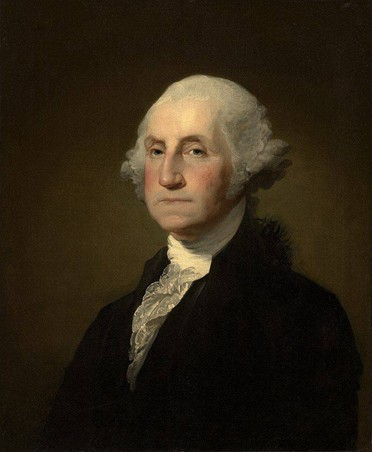

William Joseph Williams, commissioned by Alexandria-Washington Masonic Lodge No. 22.

Note the Sun and the Compass, representing the illumination and design of the Great Work

The records of Fredericksburg Lodge covering a part of his early Masonic life were lost or destroyed. From 1753 to 1775, his opportunities to visit organized Masonic bodies were probably few due to his military engagements on the frontier until 1758 and his subsequent life as a planter at Mount Vernon, which was nearly fifty miles from his home Lodge. However, it is believed he maintained his fraternal associations when opportunity permitted.

Many years later, Washington was named in the charter as the first Master of Alexandria Lodge No. 22 under the Virginia jurisdiction on April 28, 1788. He served as Master until December 20, 1788, when he was unanimously re-elected for a full term. He served in this role for about twenty months. Three years later, Washington, escorted by his Lodge No. 22, assisted in laying the cornerstone of the District of Columbia, under the aegis of Pierre Charles L'Enfant, improved by Andrew Ellicot and his surveyor Benjamin Banneker.

It is worth noting that while Washington received many honors from Masonic bodies, he never assumed Grand Lodge office (such as Grand Master of a state). There were discussions among American Masons about potentially creating a national Grand Master position for Washington, but he politely publicly declined any such elevation, preferring to remain a humble member and leader of his local lodge.

Upon his retirement in 1797, Washington received addresses and congratulations from his own Alexandria Lodge No. 22 and the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts. He replied to these with expressions of his continued affection for the Fraternity. It is noted that he also attended a meeting and dinner with Alexandria Lodge No. 22 after his retirement, offering a toast to the Lodge and all Masons. He also corresponded with individuals questioning the loyalty of the Masonic Fraternity, firmly defending its principles.

Washington supervised the design choices of Washington D.C., which were rendered according to occult geometry and other factors.

At his death on December 14, 1799, Freemasons took part in bidding farewell to their illustrious brother. On December 18, 1799, Washington's burial at Mount Vernon was accompanied by an official Masonic funeral rite conducted by the members of Alexandria Lodge No. 22.

HIS FAITH

Though mainstream history regards Washington as a Christian and nothing else, the reality is far more nuanced. Washington, in his speeches, seldom dabbled in Biblical references, and Washington was somewhat disinclined to refer to "God" in the sense Christians tended to in the syntax of the time, referring most of all to "Providence" or an "Almighty" power, with references to "God" only occurring a minor 146 times, with many of them being colloquial expressions and little else.

There are no known references to Washington ever referring to "Jesus" or "Christ" or any combination thereof, with many of Washington's contemporaries referring to him as a "deist". Eyewitnesses claim that Washington always prayed in a meditative state at dawn regardless of the time of year.

Indeed, Christians to this very day have found themselves unable to reconcile with the anti-Christian sentiments of many of the Founding Fathers, and the blatant Hellenism of early United States. Nothing shows this more visually than the Capitol Building itself, styled after the ancient Temple of Poseidon of Athens.

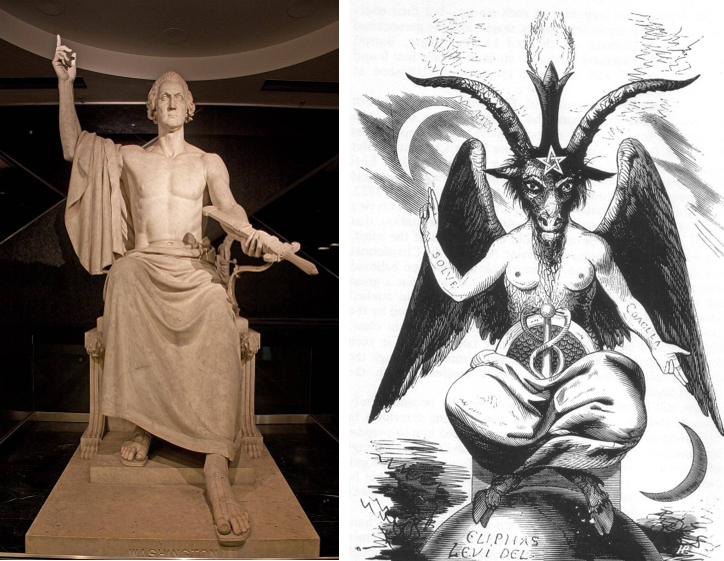

The Enthroned Washington of Horatio Greenough even shows Washington in the direct likeness of Zeus, postured with the symbolic stance of the "as above, so below" almost any Zevist would recognize.

Most apparent of all, however, is the Apotheosis of Washington with the Capitol Building.

With the knowledge that apotheosis means the elevation of something into a divine state, or effectively, "man unto god", seeing Washington seated among the Pantheon of Greek Gods can only be seen one single way; that Washington, due to his deeds in life, had earned his place among them.

Further Reading:

- A wonderful source of information on all things Washington

- A fascinating breakdown on the Zevist motifs and mindsets of Washington and the Founding Fathers

- An important distinction of the Freemasons as they were versus what they became

- The aforementioned letter Washington sent to a friend, regarding his concerns of the growing corruption of the Freemasons

- Washington The Man and The Mason, Charles H. Callahan

- How did Freemasonry Influence the Design of Washington, D.C.? Masonic Philosophical Society, Elaine Paulionis Phelen

CREDIT:

Arcadia

[TG] Karnonnos (Early Life and Washington as Mason sections, references to his religious beliefs)

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe