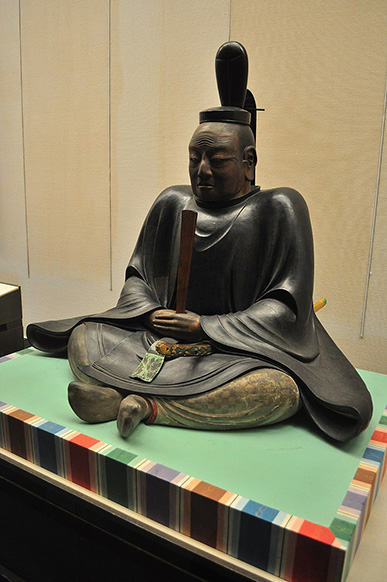

Tokugawa Ieyasu

Great Shogun

Tokugawa Ieyasu was the most powerful Shogun of Japan and one of the few rulers in history to successfully extirpate the program of the enemy from his realm. Domestically, in addition to methodically uniting the country through military genius, he created an enduring peace in Japan and a completely transformed social, legal and military order that lasted two hundred and fifty years.

HOSTAGE

Tokugawa Ieyasu was born under the name Matsudaira Takechiyo on the 31st January 1543 at Okazaki Castle in the province of Mikawa. The Matsudaira clan was a minor samurai family wedged between two powerful neighbors: the Imagawa clan to the east (Suruga Province) and the Oda clan to the west (Owari Province). His father Matsudaira Hirotada and mother Odai-no-Kata were rather young even by Japanese aristocratic standards, being pressured to provide an heir.

His father soon divorced Odai-no-Kata as a result of her family siding with the Oda clan. This left Hirotada in a dubious position, which compelled him to customarily send his son as a hostage to Imagawa Yoshimoto to secure the survival of the family as a whole. Oda Nobuhide, father of the future ruler of Japan named Oda Nobunaga, intercepted and abducted the young child. Thus, at the age of six, Ieyasu became a hostage of the unintended clan.

Young Ieyasu spent about two years in Oda custody, primarily in Owari Province. Despite being essentially a prisoner taken for leverage, he was reportedly treated reasonably well by the Oda family, in spite of his father’s refusal to switch sides. However, Ieyasu’s father Hirotada was assassinated by his own retainer, plunging the balance of power into chaos.

The Imagawa decided to strike and seized the Matsudaira home castle of Okazaki. They also attacked the Oda-held stronghold of Anjou. In the fighting, the Imagawa captured Nobuhiro, one of Nobuhide’s sons (the half-brother of Nobunaga). Ieyasu was then exchanged as a hostage for the son of the other clan.

IMAGAWA

As a more glorified hostage, the Imagawa domain was stable and cultured, which provided a relatively secure environment for the young Matsudaira lord. Ieyasu was soon reunited with a few Mikawa vassals who had also come under Imagawa service, and he began receiving education and training appropriate for a samurai of his rank. According to English and Japanese historical accounts, Ieyasu was tutored in military and political arts. He learned strategy, governance, and etiquette as befitting a future daimyo.

Ieyasu also had certain habits and hobbies he cultivated throughout his life. He was an advocate of falconry and a prolific swimmer.

One of Ieyasu’s important mentors in Sunpu was the Imagawa clan’s advisor Taigen Sessai. Sessai, a learned Zen monk and strategist, took charge of Ieyasu’s intellectual and strategic education. Under Sessai’s guidance, Ieyasu studied the Chinese classics (the Four Books and Five Classics of Confucianism) and revered military texts like Sun Tzu’s Art of War and the Rikuto (Six Strategies). Sessai even posed Zen riddles to the boy, honing Ieyasu’s mind towards both spirituality and tactics.

These formative lessons instilled in him a deep love of learning and a prudent, long-term approach to challenges based on his ability to meditate and to maintain a crystal clear mind. Historical chronicles noted that despite the nature of his captivity he was by his early teens effectively a junior officer in Imagawa Yoshimoto’s service. Furthermore, he observed council meetings and by the late 1550s was even leading troops on Imagawa Yoshimoto’s behalf in local campaigns.

In 1555, at about fourteen years old, Ieyasu (still called Takechiyo at the time) underwent his coming-of-age ceremony under Imagawa auspices. A year and a half after coming of age, Ieyasu entered into a politically important marriage arranged by his lord, the fifteen-year-old Ieyasu married Tsukiyama-dono, the niece of Imagawa Yoshimoto.

Two years later, the leadership of the Oda clan had passed to Oda Nobunaga. In 1560, Imagawa Yoshimoto, leading a army of 25,000 men, invaded the territory of the latter. Ieyasu was tasked with besieging the castle of Marune, yet while doing so his lord died at the Battle of Okehazama. Still a teenager, upon hearing of this he took the opportunity to declare independence, putting an end to his status as a hostage.

He cultivated a close friendship with the famous swordsman Hattori Hansou of the same age at this time, who became his most loyal knight and companion. Following this, he approached Oda Nobunaga to form an alliance, the Kiyosu Alliance.

VASSAL OF NOBUNAGA

Ieyasu first had to deal with the uprising of the Ikkou-Ikki Buddhists, whose extreme ideas of ‘salvation on earth’ by destroying earthly hierarchy (the so-called ‘True Pure Land Buddhism’) stood in opposition to the relatively orthodox tradition of Pure Land Buddhism he followed. The Portuguese had also been supplying this movement with heavy arms in exchange for slaves. His lord Nobunaga also found exterminating this group to be of high importance, as they blocked important trade routes.

At the Battle of Azukizaka, he nearly was killed by a volley of bullets yet managed to overcome the rebel monks with a display of military ingenuity and personal command.

Ieyasu accompanied Nobunaga in his conquest of and riding into Kyoto. He continued to consolidate power over the province of Mikawa, eventually establishing control of the entire area. During this time, Ieyasu already created a tripartite system of governing his territories and dividing his generals into a central wing of the most loyal designed to protect him, the group of the west and the group of the east.

TAKEDA CLAN

Ieyasu became embroiled in a war with the Takeda clan after they switched allegiances away from Nobunaga. At the Battle of Mikatagahara, Ieyasu faced a staunch defeat by the much larger forces of Takeda Shingen. He created a very risky feint in allowing the remnant of the forces to come in the gates of the home Tokugawa castle with a display of drums and flames as the enemy forces pursued them, which made the enemy side suspicious he was luring them into a trap. Takeda Shingen called off the offensive and soon died.

The Japanese leader on the ascendant was adept at psychological warfare, which he continued to use as the Takeda clan pressed forward. In 1575, Takeda Katsuyori attempted to attack Mikawa, being repulsed by Nobunaga and Ieyasu in a combined show of arms.

Ieyasu quickly manovered to isolate the Takeda clan by encircling their province with five quickly constructed castles. This effort ended in the Battle of Tenmokuzan and his most hated enemy was completely annihilated.

NAGASHINO AND POWER VACUUM

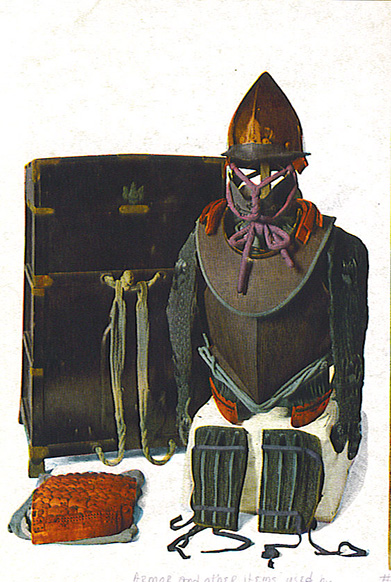

He then solidified his position as one of Japan's preeminent daimyo through strategic military and political actions. Beginning with the decisive Battle of Nagashino in 1575, Ieyasu, allied with Oda Nobunaga, successfully defeated the powerful Takeda clan. His forces notably utilized innovative matchlock firearms, helping secure victory and signaling his rising military reputation. This triumph significantly weakened the Takeda, allowing Ieyasu to assert greater control over eastern provinces.

Between 1576 and 1582, Ieyasu methodically expanded his territory and influence through persistent warfare and diplomatic skill. Following the collapse of the Takeda clan in 1582, accelerated by the defeat and death of Takeda Katsuyori at the Battle of Tenmokuzan, Ieyasu seized former Takeda territories, significantly increasing his domain. However, the sudden assassination of Oda Nobunaga in 1582 [the Honnou-ji Incident] placed Ieyasu in grave danger, temporarily isolating him amidst hostile territory and forcing a perilous retreat back to his stronghold in Mikawa.

In the chaotic power vacuum following Nobunaga's death, Ieyasu initially considered capitalizing on the confusion to enhance his own position. However, he cautiously chose diplomacy and strategic restraint, negotiating carefully with Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who swiftly rose to prominence as Nobunaga's successor. Throughout 1583 and 1584, Ieyasu remained watchful, navigating alliances and maintaining independence, wary of Hideyoshi’s rapid consolidation of power across central Japan.

The delicate balance broke in 1584 during the Komaki-Nagakute campaign, a brief but fierce conflict between Ieyasu and Hideyoshi. Despite his initial military successes, including tactical victories at battles like Nagakute, Ieyasu recognized the immense resources at Hideyoshi's disposal and wisely agreed to peace terms, pledging loyalty while retaining considerable autonomy. By 1585, Ieyasu had thus skillfully secured his domain and preserved his military strength, laying the foundation for his future ascension as the ultimate ruler of Japan.

HIDEYOSHI TOYOTOMI

Under Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Tokugawa Ieyasu initially served as a powerful ally, submitting strategically after recognizing Hideyoshi's rising dominance following Oda Nobunaga's death. After pledging loyalty in 1586, Ieyasu became one of Hideyoshi’s most trusted commanders, aiding significantly in consolidating Hideyoshi's power across Japan. His cooperation solidified Hideyoshi’s rule by demonstrating unity among major daimyo, especially given Ieyasu’s prominent status as the leader of the resource-rich Kanto region, which he was assigned to govern in 1590 as compensation for loyalty.

Ieyasu played a critical military and administrative role during Hideyoshi’s reign, actively participating in campaigns such as the Siege of Odawara (1590), which effectively subdued the Hojo clan. His governance of the expansive Kanto domain allowed Hideyoshi to confidently direct attention to other affairs, notably the Korean invasions in the 1590s. While Hideyoshi pursued foreign expeditions, Ieyasu skillfully managed his territories, quietly strengthening his military and economic position, gaining further respect among samurai and commoners alike for stable governance.

Upon Hideyoshi’s death in 1598, Ieyasu, who had carefully cultivated influence and alliances, emerged as the most powerful figure among the council of regents established to govern until Hideyoshi's heir matured. Having gained substantial experience and prestige during Hideyoshi’s rule, Ieyasu skillfully maneuvered to consolidate authority, causing him to face off against enemies who formed the powerful western army. Ieyasu’s service under Hideyoshi strategically positioned him to inherit supreme leadership over Japan.

BATTLE OF SEKIGAHARA

The leader of the eastern army now faced off against his enemies. They occupied a wide line, outnumbering his troops by 20,000 to 40,000 estimated men.

Ieyasu’s infamous ‘Red Devils’ started the battle with a fearless charge, yet Mitsunari’s forces held advantageous positions, and the battle commenced with fierce fighting, resulting in heavy casualties on both sides.

As the day progressed, the pivotal moment occurred when several commanders on Mitsunari’s side, most notably Kobayakawa Hideaki defected to the Tokugawa army after Ieyasu used another psychological technique of firing warning shots at Hideaki's army, causing him to panic.

This sudden betrayal dramatically shifted momentum, causing confusion and panic among Mitsunari’s remaining forces. Capitalizing on the chaos, Tokugawa’s forces launched a coordinated attack, swiftly overpowering the Western Army and securing a decisive victory. The battle concluded by late afternoon, effectively ending resistance against Tokugawa’s dominance and paving the way for the establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

SHOGUN

Tokugawa Ieyasu now became Shogun of Japan, being able to access this title on assent from the emperor account of his noble background. He was given near-total powers. Upon becoming Shogun in 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu secured substantial political authority, granting him ultimate control over Japan's feudal government. He centralized power by establishing Edo (modern-day Tokyo) as the political and administrative capital, making it the epicenter of governance. Through a carefully structured hierarchy, Ieyasu positioned the Tokugawa family above all daimyo, who were compelled to pledge allegiance, submit hostages, and regularly travel to Edo under the alternate attendance (sankin-koutai) system, solidifying direct political oversight.

Militarily, Ieyasu wielded supreme authority, taking direct command of all samurai forces across Japan. He implemented rigorous military reforms, solidifying a clear chain of command centered around loyalty to the Shogunate (One Man, One Castle doctrine). Ieyasu's regime strictly regulated castle-building and military mobilization, allowing him to prevent potential rebellions and reduce inter-clan warfare. This ensured peace and established the foundation for the Tokugawa peace (Pax Tokugawa), characterized by a lasting stability throughout his rule.

He soon abdicated the post in 1605 to give power to his son Hidetada but continued to rule Japan from the shadows in combination with his child, who proved a rather dynamic leadership.

SOCIAL POLICY AND LAW

The Tokugawa Shogunate divided the people into four classes of farmers, artisans, warriors and merchants, a system called shinoukoushou. Samurai were given an elite status and were allowed to carry weapons but were also forced to exhibit proper decorum. While the concept of separating samurai from commoners had roots in Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s policies, it was under Ieyasu and his successors that the system was definitively codified and enforced, as he was eager to avoid the centuries of rebellion.

ECONOMIC REFORMS

Ieyasu also upheld the land survey and taxation system established under Hideyoshi. The Taikō Kenchi (grand land survey) had assessed the productivity of farmland throughout Japan in terms of koku of rice. His administration largely maintained these assessments as the basis for taxing the peasants and determining each daimyo’s ability to provide.

This kokudaka system meant that a domain’s responsibilities such as how many troops it must supply or the contribution it must make to public works were tied to its assessed rice yield rather than just its size. In keeping this standardized fiscal measure, Ieyasu ensured fairness in the obligations of each han and prevented local lords from arbitrarily overstating or understating their wealth.

In domains transferred or newly created after Sekigahara, new surveys were conducted to update their kokudaka, bringing them in line with Tokugawa records. Japan’s feudal economy now was overseen with bureaucratic precision.

Farmlands doubled in size with rice yields increasing steadily, supported by the maintenance of peace. Extensive mining projects became prevalent in Japan, including the Sado gold mine, which quickly became one of the world’s main sources of gold.

Edo had become not just a political center but a booming economic hub with a dedicated base of artisans, large consumer population and thriving markets. Osaka and Nagasaki, under the Tokugawa watch, continued to prosper as Japan’s rice markets window to foreign trade, respectively, but all within the constraints the shogunate imposed.

Unifying the currency was another major reform Ieyasu pursued to promote economic efficiency. In the late Sengoku period, Japan’s circulation of money had been a patchwork of confusing systems. Ieyasu decided to create a central currency of uniform weight gold and silver.

To assert control, in 1601, Ieyasu announced that any ship sailing abroad from Japan must carry a special license, the so-called Red Seal, being a letter with the shogun’s vermilion seal (shuin). These shuinjou permits, issued by the bakufu, granted exclusive trading rights to the holder and were shown to foreign authorities as proof of official sanction. This system allowed Ieyasu to eliminate unlicensed pirate trading and monopolize profits. Japanese ships in the early 1600s ventured to places like Siam, Annam, and Luzon, bringing back profitable goods.

THE JAPANESE CHURCH

Christianity was first introduced to Japan in 1549, when Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier arrived in Kagoshima. Jesuits and Franciscans quickly scaled their operations. By 1582, roughly 150,000 Japanese had converted to Christianity, including peasants, samurai, and even some daimyou (feudal lords).

Oda Nobunaga patronized the Jesuits against his Buddhist enemies like the Ikkou Ikki, unaware that they had collaborated in some regards. Toyotomi Hideyoshi initially welcomed the newcomer religion, but he quickly grew heavily suspicious of their influence and blamed the missionaries for inciting intolerance. Furthermore, worrying reports seemed to indicate the areas of heavy Catholic Church activity were sending endless Japanese slaves to New Spain (Mexico).

The pilot of the wrecked San Filipe galleon reportedly boasted that Catholic missionaries paved the way for conquest of the Philippine islands, which led Hideyoshi in a rage to execute dozens of Christians at the end of his reign. Still, Hideyoshi tolerated conversions among the lords so long as they did not engage in missionary activity.

Ieyasu’s triumph over the latter’s forces in 1600 came with an observation that many lords of his ex-master had converted to the new faith. The English and Dutch representatives of trade also warned him about the Catholic Church. Still, he attempted to remain open-minded over the next decade, particularly in trying to acquire Spanish technology to operate his gold mines. He even had a Portuguese Jesuit at court, João Rodrigues.

Problems were sparked by the Nossa Senhora da Graça incident, where a Portuguese official named André Passoa had earlier executed fifty Japanese samurai in Macau for insubordination. A year later, Pessoa’s ship to Kyushu (the province of most Christian activity) was inspected by Hasegawa Fujihiro who suspected seditious intent in supplying arms to potential rebels and reported this to Ieyasu. The Jesuits attempted to mediate the situation and to manipulate in order to silence Pessoa and minimize the issue, but the Portuguese official complained.

On the ship, Pessoa received information he would be soon executed by Ieyasu, which provoked him to attack the Japanese base and three days of fighting ensued with the forces of the Lord of the Shimabara Domain named Arima Harunobu, who was also a Christian. Pessoa perished and the majority of his crew were killed. The Lord of Shimabara attempted to intervene for the Jesuits to Ieyasu to no avail, as they had disgraced themselves in his eyes.

The 1612 Okamoto Daihachi incident was a turning point. Daihachi, a Christian retainer, was implicated in a corruption and bribery scandal as Harunobu had sent him a major bribe to purchase lands for him, a serious offense that contravened the recent law codes of samurai conduct.

Ieyasu retrieved information from investigations and spies that a large circle of converted lords surrounding Harunobu were planning to assassinate and remove him and his son with funding traced directly to the Catholic Church. Harunobu, who was so extreme that he himself had desecrated and destroyed forty temples in Shimabara, also desired revenge for being forced to adhere to the shogun’s order to sink a fellow Christian’s ships.

That year, Ieyasu began to take action. In April 1612, while in his retirement base at Sumpu, he issued a ban on Christianity in the Tokugawa family’s domains (including areas like Edo, Sumpu, and Kyoto). This preliminary Edict ordered church buildings torn down and prohibited missionary preaching in those areas. He executed and made an example of Harunobu.

BAN ON CHRISTIANITY

Over the next two years, more disturbing information reached Ieyasu’s ears. He and other Tokugawa officials began to note the Christian tendency to worship and flock to the condemned and to glorify criminals, which did not just cause consternation among them but outraged the general public to the point of inflaming disorder in the realm he had meticulously endeavored to make stable.

The Catholic Church also acted with extreme arrogance. Numerous incidents of destruction of Temples by zealous Catholics had occurred since the 1560s but only seemed to increase in prevalence the more that Ieyasu was given promises it would stop. The ecclesiastical authorities and Jesuits themselves became major landowners, siphoning assets from the Japanese nobility. Plurality of religion in Japan was threatened.

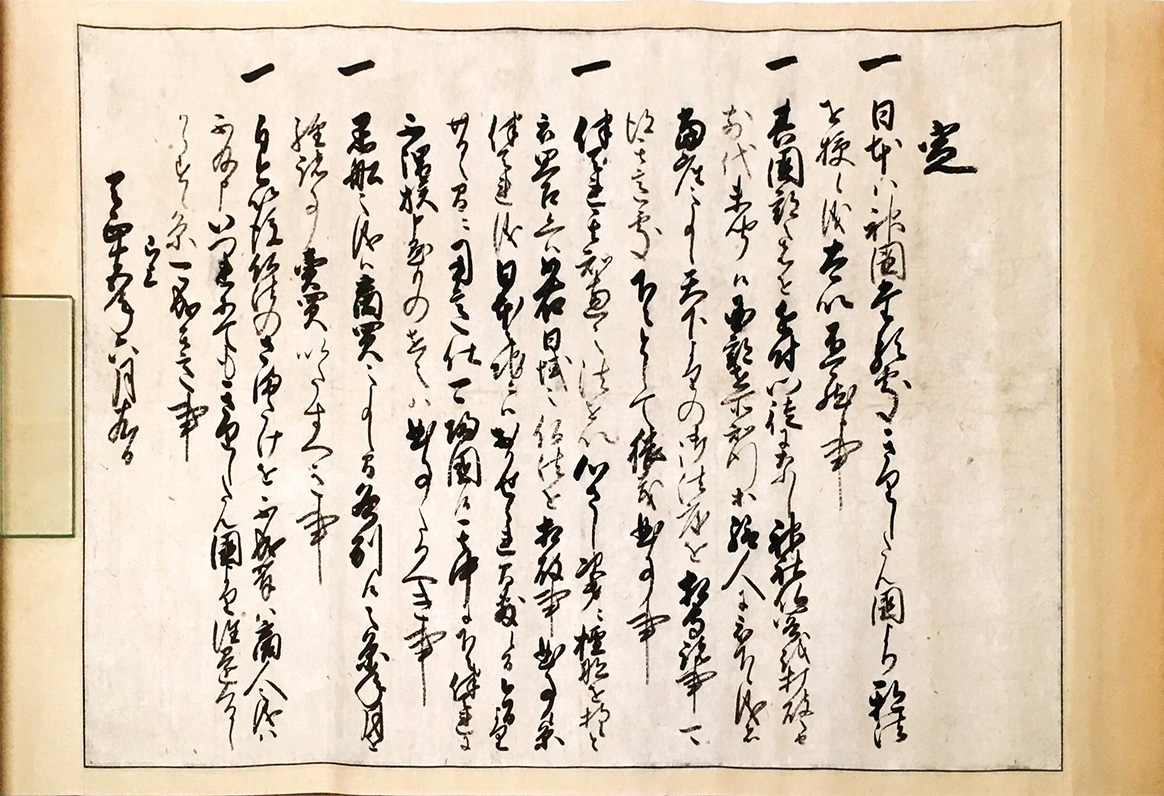

He tasked his advisor, the Buddhist monk Ishin Suuden, to draft a document justifying the eradication of the Christian faith. On January 27, 1614, the Tokugawa regime promulgated a sweeping edict banning Christianity nationwide:

爰吉利支丹之徒党、適来於日本、非啻渡商船而通資材、叨欲弘邪法惑正宗、以改域中之政号、作己有、是大禍之萌也、不可有不制矣。

Yet the Christian band have come to Japan, not only sending their merchant vessels to exchange commodities, but also longing to disseminate an evil law, to overthrow right religion, so that they may change the government of the country, and obtain possession of the land. This is the germ of great disaster and must be crushed.

彼伴天連徒党、皆反件政令、嫌疑神道、誹謗正方、残義損善、見有刑人、載欣載奔、自拝自礼、以是為宗之本懐、非邪法何哉。

The Jesuit bands [Christians] contravene governmental regulations, slander Shinto, calumniate the True Law, destroy social harmony, and corrupt goodness. When they witness people being punished they exult and rush about, bowing and prostrating of their own accord, counting such conduct the very fulfilment of their religion. What, if not an evil creed, could this be?

伴天連門徒御制禁也。若有違背之族者忽不可遁其罪科事。

The Sect of the Padres is hereby prohibited. If any persons violate this, they shall not escape punishment for their crime.1

Ieyasu’s government rounded up priests and forced them onto ships bound for Macao or Manila, effectively exiling them. Even prominent Japanese Christian lords were expelled: the samurai convert Takayama Ukon was banished and sent overseas with protectees, eventually dying in exile in the Philippines. Any daimyo who failed to uproot Christianity in their domain risked severe punishment. This put pressure on formerly lenient officials.

Families were required at Temples to register annually as Buddhists or followers of Shinto. Cells of families within each and every precinct of Japan were required to keep watch over any signs of Christian proselytism.

A year after the Edict above, the Catholic Church demanded to Hidetada that a permanent military fortress be built, which further inclined the latter to make a grisly example of Christians.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Bateren Expulsion Ordinance

Japan: From Prehistory to Modern Times, John Whitney Hall

日本国際政治学会『徳川日本の対外貿易 (Foreign Trade of Tokugawa Japan)

Heritage of Land Development

What were the reforms of land surveys, fiefs, and tax systems under the auspices of Ina Tadatsugu, the civil administration brain behind Tokugawa Ieyasu's five Kanto provinces?, Takayuki Emiya

The Shogun’s Silver Telescope: God, Art, and Money in the English Quest for Japan, Timon Screech

Bakuhan system, Britannica.com

Tokugawa Shogunate: Japan’s Era of Peace and Isolation, Max M, sengokuchronicles

CREDIT:

[SG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe