Ptahhotep

Great Philosopher

Ptahhotep was an official of great spiritual and stately eminence during the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt. During his lifetime, he served as the chief minister of the Egyptian court under the Pharaoh Djedkare Isesi. As an expert of the Zevist path, the wisdom of his mouth gave great concourse to a set of spiritual literature named the Maxims of Ptahhotep, a work that proved to be of deep focus and importance for Egyptians aeons after his time.

THE OFFICIAL ROLE

The vizier of the Egyptians came from a humbler background than Ptahhotep’s later greatness would suggest. Although his family was politically well connected within the Memphite spiritual brotherhood in the ancient capital of Egypt as nobility, his father and mother only hailed from cadet branches of it and therefore, his rise in the Egyptian hierarchy was not necessarily a fait accompli.

Nonetheless, at some point, after witnessing his immense talent in sacred matters, a related powerful vizier named Akhethotep formally adopted him as his spiritual son. Akhethotep is recorded as holding titles such as Supervisor of the Pyramid Cities and Overseer of the Treasuries under the Pharaohs Niuserre, Menkauhor, and Djedkare, therefore he was an elder contemporary in the family and of quite a supreme level of importance.

Ptahhotep himself became indispensable to the Egyptian state in endless ways. In addition to being the Vizier1, he held many other important positions, such as Overseer of the Treasury, Overseer of Scribes of the Pharaoh’s Document, Overseer of the Double Granary and Overseer of All Royal Works.

His divine status is shown by indications of royal affiliation, which in later traditions marked him out as “the eldest son of the Pharaoh,” in this case referring to Djedkare Isesi. The protocol of adoptions in Egypt involved a divine bestowal, so the mention of Ptahhotep as a son by the wearer of the Two Crowns has spiritual overtones relating to a glorious progression in the path that passes into eternity.

EGYPTIAN OFFICIAL

Ptahhotep was the chief executive of the royal court; he ran the day-to-day machinery of the Pharaoh’s office. It was his job to control the nobility of Black Land and to keep intrigue to a minimum, being indispensable to the great ruler. His pursuit of wisdom was honed very much in this high office, a role he occupied diligently for decades.

The vizier was also one of the chief judges of Egypt. Scenes from the life of Ptahhotep were represented in his presiding over court cases, particularly those tied to the complex Egyptian administration. The legal dimension of his efforts also informed his contribution to sacred literature well, because as a judge he understood what caused the majority of crimes.

His responsibilities also included the top-level civic oversight of the administrative capital, which in the Old Kingdom context meant the royal residence region and its administrative apparatus, in addition to the coordination of urban administration (i.e. architecture), the oversight of officials, and controllingspaces tied to the palace. Effectively, he was the leader of the civil service. The tasks he was endowed with were essentially endless, and it could even be said that much of the prosperity of the Old Kingdom was due to Ptahhotep’s discriminating oversight.

THE MAXIMS

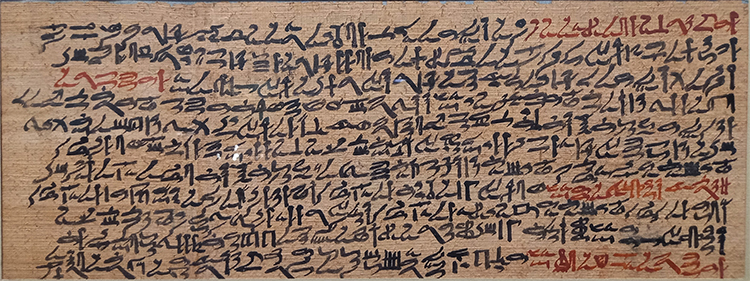

The Maxims of Ptahhotep are an Egyptian wisdom text consisting of a brief narrative prologue followed by a series of 37 aphoristic maxims. In the prologue, Ptahhotep addresses the Pharaoh and then his son, setting the stage as a father’s teaching and also showing the superlative rank his wisdom commanded. The body of the text is a collection of self-contained maxims, each typically a few lines long, which together articulate a comprehensive code of Egyptian conduct.

In the Maxim of Ptahhotep’s framed opening lines, he is explicitly styled “leader of the city and vizier Ptahhotep,” and the setting is “under… the Two Crowns… Isesi.”

The sayings of the Great Vizier are known to us from posterity through Middle Egyptian language editions that were recreated continually many years after the period of Ptahhotep. It was used in Egyptian schools and in holy settings for centuries as a cornerstone of philosophical literature, showing the eternal confidence the people had in their ancestor. Syntactically the collection is very elegant in style, having one of the highest and most graceful registers of reproduced writing in the ancient language known to us.

The majority of the text emphasizes the value of silence continually and to not waste one’s words on foolish and self-defeating endeavors. In addition, the text places a primacy on kindness and magnanimity when possible. The rejection of endless lust for power and self-defiling greed as the destroyer of man is another aspect of the text that is repeated continuously. Most of these themes have much in common with other moral literature from Egypt’s canon, emphasizing the cosmic order of Ma’at.

The ostensible content of this work is to combine simple day-to-day instructions on how to achieve sagacity and wisdom, yet peering deeper into the work, these are laden with deeper spiritual meanings – the examples chosen ultimately serve as an allegorical and mnemonic puzzle going beyond a mere moral guidebook. Legendary status afforded to these writings can be said to come from their usefulness of purpose.

Maxims of Ptahhotep2

Do not be haughty because of your knowledge,

But take counsel with the unlearned man as well as with the learned,

As no one has ever attained perfection of skill,

And there is no craftsman who has acquired mastery.

Good advice is rarer than emeralds,

But yet it may be found even among girls at the grindstones.

The point of this specific maxim, for example, is to discourage excessive haughtiness, to not deny that the wisdom of the Gods can come from any individual regardless of their rank and intelligence, for the humble laborer in contact with the natural world can see many things that the genius scholar is ignorant of. Warnings also are apparent to those proud enough to dismiss the more common aspects of life altogether, who may dismiss their peers as worthless based class distinctions or on internal self-aggrandisement.

The other point is to show that the wisest of people do not proclaim knowledge about what they do not know, but they actually see towards the margins of their own sagacity. Most mental hostility to what is unknown is underpinned by fear. Even if it be a child who is teaching, anyone seeking to be wise should aim for humility in being instructed on the fuzziest and newest of subjects alien to them.

Another thing the maxim impresses outright is to never neglect that even the most skilled and feted notable person can endlessly improve and learn new tricks as a human; the ability to perfect oneself is simply limitless. Improvement at a perceived height of greatness does frequently mean going back to the basics. For example, using the example of singing, the foundation for most skilled singers to be able to perform and maintain their voice into old age consists of frequent warmup routines before shows, taking breaks from making sounds, and keeping the throat functional by avoiding what is hazardous to its functions.

However, there is also a hidden spiritual meaning to this maxim. The example is meant to show on a deeper level that daily facets of meditation, the basics, are not to be ignored, even though those of an arrogant, impatient mindset may be tempted to see these as being as trifling as a servant girl’s gossip. In this case, the good advice is advice to help oneself that may be spurned, and the unlearned man is actually the beginner who takes on those first tasks of the initiate.

THE MASTABA OF PTAHHOTEP

The “tomb” of Ptahhotep is noted by archeologists to be particularly unique. He was interred in a mastaba, a type of flat-roofed tomb, at Saqqara, close to the famous Step Pyramid of Djoser, in a complex known as the Tomb of the Nobles, also containing Mereruka and some other notable Egyptians. The holy mastaba (cataloged as D62) is a double tomb containing dual chapels for Ptahhotep and for the elder Akhethotep.

The pioneering French archaeologist Auguste Mariette first discovered the monument in the 1850s3, as he immediately noted the relatively well-surviving features and impressive decorations in its reliefs. Later excavations and publications, such as a 1900 monograph by N. de G. Davies, revealed the full extent of the structure: a main tomb building (built by the elder Akhethotep) with a smaller attached chapel for Ptahhotep, which was so richly decorated that the entire complex came to be known by the latter’s name. An early explorer dubbed it “the most beautiful [tomb] in Saqqara” in the quality of its carved scenes.

The decorations of the mastaba of Ptahhotep are considered beautiful for their detailed painted reliefs of Old Kingdom life. On the walls of his chapel, there are vivid depictions of agricultural work, fishing and fowling in the marshes, animal husbandry and butchery, other scenes of ritual bearers, and even secular scenes of dancers and wrestlers. The tomb’s inscriptions, including Ptahhotep’s titles and invocations of the goddess Ma’at, parallel the text of the Maxims in emphasizing truth, justice, and proper use of power and conduct. Any mummy or grave goods of Ptahhotep were not present. Nonetheless, the tomb’s art and texts remain a standing source for understanding his status.

By the later dynasties, Ptahhotep had become recognized as a hero of Egypt and whose name was eternally divine.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders, Nigel Strudwick

2Maxims of Ptahhotep

3Saqqara: The Royal Cemetery of Memphis, Excavations and Discoveries since 1850, Jean Philippe Lauer

The Tomb of Ptahhotep I, Anna-Latifa Mourad and Effy Alexakis

CREDIT

[SG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe