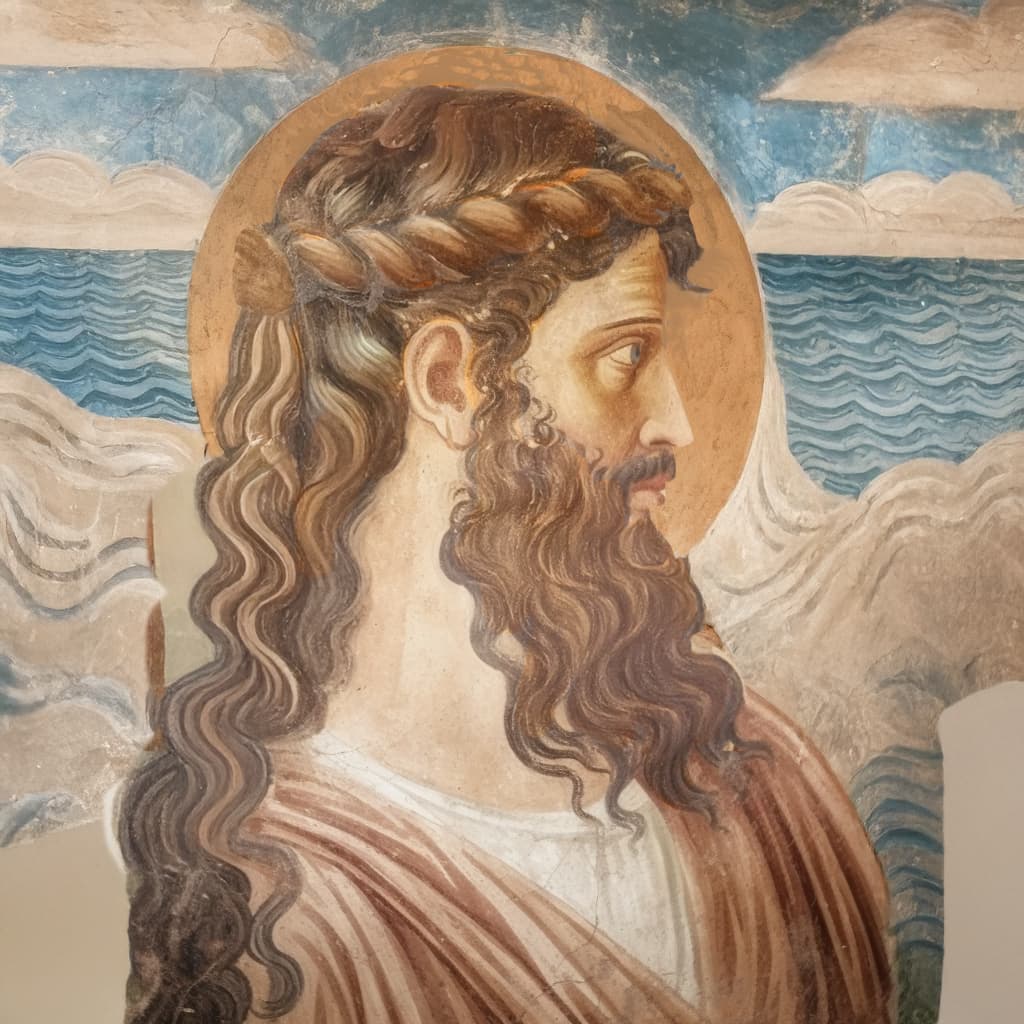

Pythagoras

Master of the Seers

Pythagoras is the father of mathematics and philosophy, whose exalted name has passed down through history as a legendary figure. He established titanic institutions of major importance in Antiquity, which were key centers of learning, religious instruction, and advancement. It was in large part due to Pythagoras that the Greek colonial cities in Southern Italy briefly became the most powerful, wealthy, and cultured parts of the Hellenic world, but the persecution of his followers soon ended this.

Becoming legendary centuries later, he was so esteemed in Antiquity that philosophers would simply refer to Pythagoras as “he” or “him.”

LONG-HAIRED SAMIAN

He was born on Samos, a Greek island in the Aegean. It is known that Pythagoras associated in his youth with the philosophers Thales of Miletus and Bias of Priene. Pherecydes the Syrian was his tutor in boyhood, whom Pythagoras is known to have cared for in his senior years. From these wise men, he learned the finer details of the sciences and the laws. The miraculous levels of knowledge he exhibited far surpassed known extents, to the point that the phrase “long-haired Samian” remained a descriptor of any wise individual for millennia.

Further travels ensued in the rest of Greece, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. Due to the beloved nature of Pythagoras, he was quickly recognized as a Demon and disciple of Azazel even during his early lifetime. Pilgrimages were made to Samos simply to be in his presence, though he was known to be taciturn.

THE CROTON EXPERIMENT

Chafing under the tyrannical government of Samos, Pythagoras departed for Croton (modern Crotone), a city of Greek colonists in the modern province of Calabria, Italy. This was becoming one of the largest cities of the Greek world and was known for its prowess in athletics, learning, and medicine. However, it was plagued by civic problems and struggles with wars against aggressive neighbors, such as the city of Sybaris.

He soon set out to build a great school and institution in the city. To join the school, however, was no easy feat. Prospective followers would have to wait years for an audience with him, and in between, learn the virtues of silence. It was a selective and rigorous process, underlined by the ambition of Pythagoras to prove that any group could be turned over to the Gods if subjected to a careful process.

Once admitted, he taught his followers to practice oversight and understand their own motivations, using certain techniques that led them to perceive the “divine eye,” as Iamblichus states. Intelligence and soul were shared by all animals, but mindfulness was something uniquely human. The great teacher thus instructed people to go inward to know themselves through meditative practices, and to curb extreme behaviors, remaking them as beings. This was necessary to resolve many of Croton’s problems, which stemmed from excess rather than deficiency.

For the Pythagoreans, numbers were considered sacred and edifying principles of the cosmos, hinting at its many mysteries. Understanding numbers led not only to the Pythagorean theorem, complex properties of shape, and other discoveries, but more broadly to the belief that everything in existence could be understood through numerical relationships. Pythagoras himself was credited with the “perfection” of the study of geometry, a pathway to the occult.

They also made copious use of maxims and symbols. Certain precepts that sound strange to us were coded phrases that held extremely complex meanings within the organization, later leading to misunderstandings even in Antiquity about the true nature of their teachings:

Ἤθελε δ᾿ αὐτῷ τὸ μὲν πῦρ μαχαίρᾳ μὴ σκαλεύειν δυναστῶν ὀργὴν καὶ οἰδοῦντα θυμὸν μὴ κινεῖν. τὸ δὲ ζυγὸν μὴ ὑπερβαίνειν, τουτέστι τὸ ἴσον καὶ δίκαιον μὴ ὑπερβαίνειν. ἐπί τε χοίνικος μὴ καθίζειν ἐν ἴσῳ τοῦ ἐνεστῶτος φροντίδα ποιεῖσθαι καὶ τοῦ μέλλοντος· ἡ γὰρ χοῖνιξ ἡμερησία τροφή. διὰ δὲ τοῦ καρδίαν μὴ ἐσθίειν ἐδήλου μὴ τὴν ψυχὴν ἀνίαις καὶ λύπαις κατατήκειν. διὰ δὲ τοῦ εἰς ἀποδημίαν βαδίζοντα μὴ ἐπιστρέφεσθαι παρῄνει τοῖς ἀπαλλαττομένοις τοῦ βίου μὴ ἐπιθυμητικῶς ἔχειν τοῦ ζῆν μηδ᾿ ὑπὸ τῶν ἐνταῦθα ἡδονῶν ἐπάγεσθαι. καὶ τὰ ἄλλα πρὸς ταῦτα λοιπόν ἐστιν ἐκλαμβάνειν, ἵνα μὴ παρέλκωμεν.

This is what they meant: “Not to stir the fire with a knife”, do not provoke the passions or the swelling pride of the great. “Not to overstep the yoke”, do not exceed the bounds of equity and justice. “Not to sit on the choenix” (a measure of grain), attend equally to both the present and the future, for the choenix represents one’s daily sustenance. “Not eating your heart”, do not waste your life in troubles and sorrows. “Do not turn around when you go abroad”, advise those departing from life not to fix their hearts on living, nor be overly drawn by the pleasures of this world alone. The explanations of the rest are similar and would take too long to recount.1

The group was under pressure to reveal little.

DISMANTLER OF TYRANTS

Pythagoras also set out to dismantle tyrants. He defied the orders of Dion of Syracuse and Phalaris of Agrigentum, both of whom imprisoned him for a time. The latter attempted to cast doubt on divination and other subjects, dismissing Pythagoras as a con artist. Abaris, a holy man from the north, assisted Pythagoras in this endeavor. The Pythagoreans pressed Phalaris with the transcendental nature of the Gods, rejecting the tyrant’s view that humans should behave identically to animals.

Through Apollo’s oracle at Delphi, they understood that the tyranny would only end when the inhabitants themselves learned Pythagoras’ arguments and ceased enabling the tyrant. This event ultimately undid the tyranny of Phalaris: he attempted to execute Pythagoras and Abaris, but died himself that very day.

In time, the Pythagoreans began to exert a strong influence on the government of Croton, which they used to promote a moderate form of aristocracy. Sybaris, a neighboring city, threatened Croton, demanding the return of prominent individuals fleeing tyranny there. Under the guidance of the divine teacher and the agitation of his followers, Croton resisted and defeated Sybaris, a victory seen as a triumph of disciplined civic virtue over Sybaritic decadence and cowardice.

Croton’s resistance to external tyrannical influences subsequently increased. It soon became the leader of a confederation of twenty-five cities in Italy, something not seen again until the rise of Rome many years later.

With Pythagoras absent, however, his followers began to attract bitter resentment from those unhappy with the group’s growing influence, particularly men like Cylon, a powerful figure rejected for admission due to his hubris and arrogance. Others chafed at the transformation of their relatives after exposure to Pythagorean teachings and viewed the order with envy. Some took issue with the inclusion of women in high positions. Others feared the Pythagorean critique of democracy.

RESENTMENT

Though adversaries of Pythagoras were aware of his divine nature and cautious not to offend him directly, their hatred of his followers burst like an abscess.

Resentment led to attempted large-scale massacres of the followers. The property of the Pythagoreans was redistributed among democratic loyalists. Within a few decades, the city fell into disrepair and chaos, requiring intervention from the Greek mainland to maintain stability. It was eventually captured by the tyrant Dionysius of Syracuse.

Croton soon decayed into a second-rate city. As a newly founded democracy, it continued to wage endless wars, never regaining its former glory. The mysterious Pythagoras, however, became a legend, his legacy enduring long after the city itself had faded.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes Laertius

CREDIT:

[TG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe