Ramesses II

Great Pharaoh of Pharaohs

Ramesses II was the greatest Pharaoh of Egypt and one of the most majestic rulers in documented history, hailed in such a way that he was regarded as the Great Ancestor of the Egyptians forever after his rule.

He greatly promoted the presence of the Gods and dramatically reversed any remaining destruction from the Amarna period. Every aspect of the Egyptian state was subjected to his reforms. Endlessly, he personified a type of active and dynamic rulership that had few detriments compared to his predecessors and successors, constantly defending Egypt’s vast borders and reviving the fortunes of the Great Civilization.

UNDER THE WING OF HAURON

Ramesses was born the child of Seti I, his adopted father and biological grandfather. He quickly became regent and demonstrated a high level of capability as a great warrior, such as helping his father take the Hittite-held city of Kadesh, riding triumphantly into it. Those around him noted his strength in administration and his ability to deliver great results in any endeavor he committed to.

Something he keenly understood was that for any civilization to thrive, it had to expand and be vigilantly defended. In this, Ramesses understood the Law of Ma’at. To fail in this meant death.

WARRIOR OF EGYPT

During the reign of Akhenaten, the country had been invaded by endless threats, such as the encroachment of the vast northern Hittite Empire under Suppiluliuma I. The false ruler ignored the pleas of all Egyptian allies in order to push the communist program of the Aten, making the borders extremely insecure. Other groups, such as the Hapiru, led a full-scale invasion of Egypt.

Although Horemheb had secured the country quite capably, and Seti I had dramatically defeated the invaders in battle, there remained a significant risk of instability, particularly as the Hittite Empire grew more aggressive, taking advantage of Seti’s death to seize the region of Amurru, which included the city of Kadesh.

Seeing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, Ramesses II immediately mobilized Egypt for war to confront threats from the North and South, alongside the Sherden sea pirates who threatened trade routes in the Nile Delta. He moved into the Levant to secure the Amurru kingdom and reestablish his father’s borders, which capitulated to him immediately. However, Kadesh remained beyond his reach.

To crush the Sherden in the second year of his reign, he strategically stationed troops and ships at key coastal locations, patiently waiting until the pirates engaged their intended targets. He then launched a surprise naval assault from hidden troops and ships, capturing all of them in a single decisive move. This shows the strategy of surprise and lightning-quick movement that he favored.

In his fifth year, he began a massive campaign to crush the Hittite presence in the Levant.

It is estimated that he expanded the Egyptian army to hundreds of thousands of men, demonstrating a level of conscription perhaps never seen before in recorded history. He also divided the Egyptian armed forces into four segments, each named after and symbolized by a distinct God: Amun, Re, Ptah, and Set.

Each division was a self-contained combined-arms unit of roughly 5,000–9,000 soldiers (including infantry, chariots, and archers), giving the army flexibility in battle. This demonstrated the great ruler’s military intuition and his desire to make the military agile, responsive, and capable of swift deployment.

Ramesses also conscripted foreign mercenaries as additional auxiliaries, but this met with limited success and often frustrated him.

BATTLE OF KADESH

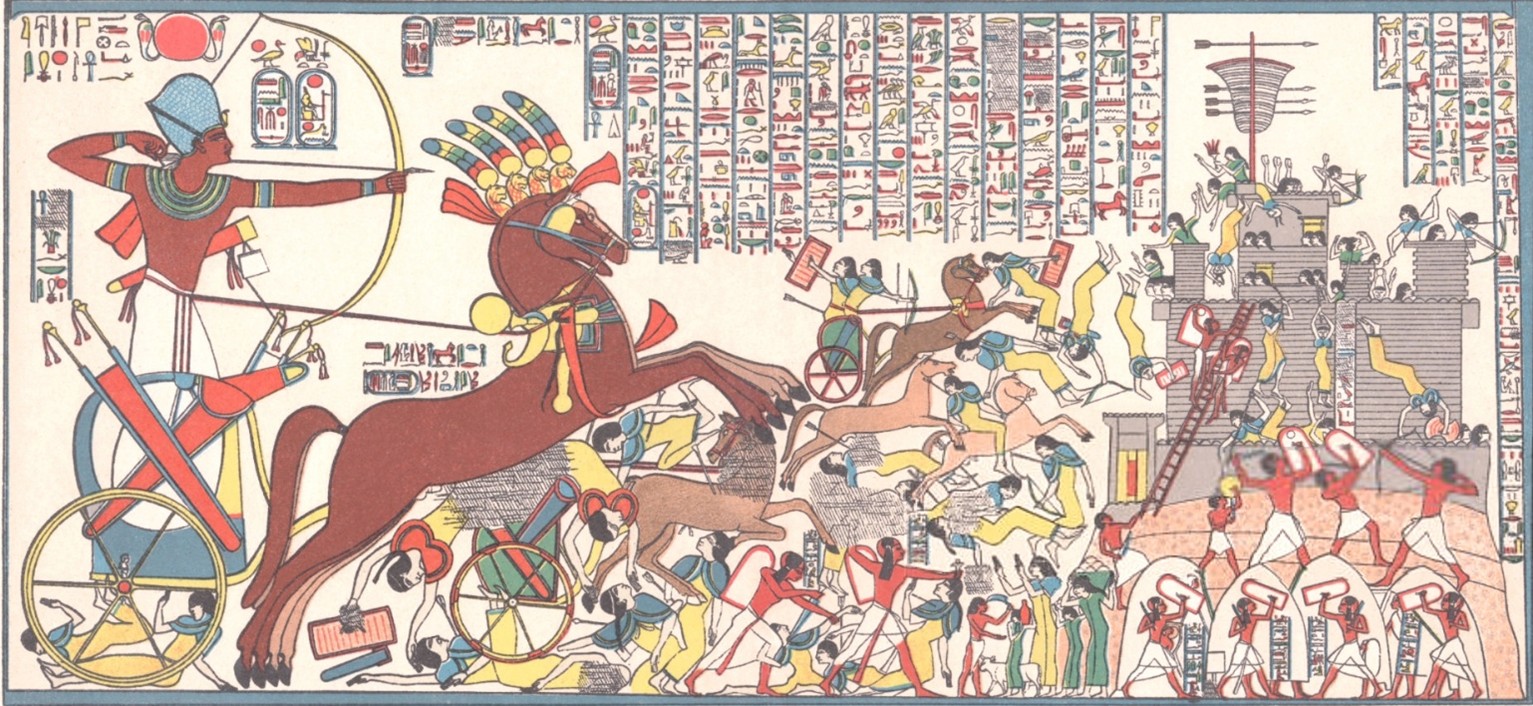

In 1276 BCE, Ramesses took part of this massive force under the aegis of Amun to the outer city walls of Kadesh, where he set up camp. The Ra, Set, and Ptah divisions remained behind, trailing this force. Unfortunately, the intelligence he had gathered turned out to be faulty: two Hittite prisoners confessed that King Muwatalli had set up camp nearby to the northeast and was preparing for battle, with a large army composed of fearsome chariot units.

Some of these chariots encountered the division of Ra, which fought bravely but suffered catastrophic losses. Emboldened by this, the Hittite army moved north to attack Ramesses’ camp and the Amun division directly. In a desperate situation, Ramesses had to act swiftly.

He bravely rallied, organized, and deployed his forces to their fullest, using the structural difficulties the chariots had in navigating the camp to his advantage, and deploying archers to maximum effect. Rallying the lighter Egyptian chariots, he encircled the Hittites and annihilated that segment of their army, then fearlessly pursued them.

King Muwatalli, watching from a distance, sent reinforcements, who, without their commander, engaged in an extremely difficult battle yet stood their ground. Loyal forces from the Amurru kingdom arrived to help encircle the Hittites once more, while Ramesses charged from the south to meet the new influx of soldiers, turning the tide of battle.

Ramesses never forgot this confrontation and attributed the survival of himself and most of his divisions to the divine favor of Amun. Inscriptions celebrate his bravery:

The Pharaoh was surrounded by two thousand five hundred chariots, and his retreat was cut off by the warriors of the "perverse" Khati and of the other nations who accompanied them: the peoples of Arvad, Mysia, and Pedasos. Each of their chariots contained three men, and the ranks were so tightly packed that they formed but one dense mass.

"No other prince was with me, no general officers, no one in command of the archers or chariots. My foot-soldiers deserted me, my charioteers fled before the foe, and not one of them stood firm beside me to fight against them." Then said His Majesty: "Who are you, then, my father Amon? A father who forgets his son? Or have I committed aught against you? [...]

I cry out with joy when he hails me from behind: 'Face to face with thee, face to face with thee, Ramses Miamun, I am with you! It is I, thy father! My hand is with you, and I am worth more to you than hundreds of thousands. I am the strong one who loves valor; I have beheld in thee a courageous heart, and my heart is satisfied; my will is about to be accomplished!'

I am like Montu; from the right I shoot with the dart, from the left I seize the enemy. I am like Baal in his hour, before them; I have encountered two thousand five hundred chariots, and as soon as I am in their midst, they are overthrown before my mares. Not one of all these people has found a hand wherewith to fight; their hearts sink within their breasts, fear paralyzes their limbs; they know not how to throw their darts, they have no strength to hold their lances." 1

A second military campaign proved more favorable: a treaty of eternal friendship was signed between Egypt and the Hittite Empire. The borders of the country were secure for the first time in three hundred years.

NUBIAN CAMPAIGN

Meanwhile, in between dealing with the Hittites, Ramesses turned his attention to the South. The two-hundred-year-long acquisition of Nubia by Egypt was threatened by southern tribes and various groups. Nubia was historically restless, and local rulers frequently sought independence from Egyptian control, especially during periods of internal weakness or transition. In particular, the chieftains of the Wawat region proved troublesome.

Dominance over Nubia, however, meant access to critical trade routes, as well as sources of gold and the associated mining operations, ebony, ivory, cattle, and laborers, resources critical to Egypt’s wealth and prestige.

At the Battle of Beit el-Wali, Ramesses used Egyptian archers to their fullest extent to shatter the rudimentary methods of the rebels. He also deployed his light chariots to great effect in the flatlands of the south.

Similarly, in the temple of Wadi es-Sebua, built by Ramesses’s viceroy of Kush, inscriptions record the king’s might over the “southern foreign lands.” On a stela at this site, Setau, the viceroy, dutifully reported that “there are no opponents of His Majesty in Nubia,” as “the tribute of the southern countries flows into the treasury” by his command.

The lands of Kush are pinioned…"2

BUILDING PROGRAM

By the third year of his reign, Ramesses resolved to create the most ambitious building program Egypt had ever seen, despite his ongoing military campaigns to enlarge the borders of the Black Land. Every aspect of the Egyptian state and civilization received his personal stamp. He set out to refurbish tens of thousands of temples, beginning with major construction work in the ancient seat of religion, Thebes.

A profound belief in the Gods underpinned his decision. He understood that the disaster of the Amarna Period, headed by the deviant Akhenaten, had befallen Egypt due to neglect of the Gods and improper manners in society. His highest priority was to eliminate any remnants of this blight upon the land.

Architecturally, Ramesses II also invested in practical constructions. He built or improved fortresses and water wells along Egypt’s frontiers (the “Ways of Horus” in Sinai had forts spaced a day’s march apart, maintained since his father’s time).

He may have dug canals to facilitate the transport of obelisks and stones. For instance, some credit him with a canal connecting the Nile to the Red Sea, though evidence is scant. Within cities, he renovated royal residences. At Thebes, he upgraded the old Malkata palace area; at Memphis, he built a new palace next to Ptah’s Temple. All these works employed advanced engineering for the era, including drag sledges for moving colossal statues and ramps for raising them.

On top of this, he constructed a massive city in northern Egypt named Pi-Ramesses, hoping to shift the focus of civilization northward to support the expansion of the state.

REFORMS OF THE STATE

International trade and tribute significantly enriched Egypt during Ramesses II’s reign. His military campaigns in Canaan and Nubia initially brought in plunder and tribute. From the Canaanite cities he reconquered, he received shipments of silver, copper, livestock, and laborers; from Nubia came gold, ivory, ebony, animal skins, and captives. After establishing dominance, Ramesses maintained vassal treaties that obligated Syrian city-states to send annual tribute, effectively funneling wealth into Egypt without requiring constant warfare.

Egypt’s agriculture, the backbone of its economy, flourished under his stable administration. The Nile’s annual floods were harnessed by maintaining irrigation works and possibly digging new canals. In years of good inundation, Egypt produced grain surpluses large enough to be stored in royal granaries. These surpluses not only fed Ramesses’s massive workforce (which built his monuments) but also allowed for generous distribution when needed.

The peace treaty with the Hittites further expanded Egypt’s trade horizons. With hostilities ended, caravans traveled freely between the Nile and Anatolia. Egyptian wheat, flax, and manufactured goods (papyrus, linen, glassware) could be exchanged for Hittite silver, Anatolian copper, and possibly horses. There is evidence that Egyptian grain was sent to Hatti during a famine in Hittite lands shortly after the treaty, indicating large-scale export capacity.

Ramesses left much of Egypt’s administration to his sons, such as Amun-her-khepeshef and Merneptah, who essentially ruled as co-regents. This collaborative approach to rulership aided him greatly in his military efforts. Although Ramesses outlived most of his sons, his policies ensured a smooth transition of power to Merneptah, making him the first royal-born hereditary Pharaoh since Tutankhamun.

Having married her as a teenager, the Great Pharaoh tirelessly promoted and elevated his wife Nefertari from the first year of his reign, naming her “She Whom the Sun Shines For,” among other titles. The two conducted rituals of high importance in perennial union, such as the Raising of the Mast of Amon-Ra. He also promoted his daughters, such as Meritamen and Baketmut, who were consecrated in many statues and inscriptions.

RELIGIOUS POLICY

His reign was characterized by a fervent commitment to traditional Egyptian religion, combined with shrewd management of religious institutions. He positioned himself as a restorer and champion of the orthodox Gods such as Amun, Ra, and Ptah, to cast off the shadow of the Amarna Period. To that end, Ramesses himself became a High Priest of Ptah, initiated into major mysteries.

Yet he also impressed upon Egypt his own divine status. He did not institute radical theological changes; rather, his reforms involved expanding state cults, building temples, and balancing the power of priesthoods to ensure the Dual Crown’s supremacy in spiritual matters.

One of Ramesses II’s earliest religious acts as Pharaoh was asserting control over the influential Amun priesthood. As mentioned, he appointed Nebwenenef as High Priest of Amun at Thebes immediately upon taking power. Several of Ramesses’s sons also served as High Priests of Amun, showing that they received serious religious instruction.

At the start of his reign, he traveled to Thebes for the Opet Festival, joining the processions as Amun’s statue was carried from Karnak to Luxor. His presence at such rites underscored the idea that the Pharaoh was the Gods’ chief servant on Earth. It visually affirmed harmony between the throne and the priesthood, important to reestablish the concept of Egypt as a divine civilization under Amun’s gaze.

One particular God who received much attention from Ramesses was Set. This was not, as some modern historians assume, to balance out the political influence of the Amun priesthood. Firstly, Set was the patron of his family, being the namesake of his father. Secondly, Ramesses used Set’s imagery symbolically to move Egypt away from ignorance and darkness, initiating a process of restitution. The borders of the state were also ruled by this God, and Ramesses utilized his symbolism to emphasize the urgency of foreign threats.

He is recorded as “favoring the God Amun above all other divinities” by Year 28 of his reign, as evidenced by inscriptions from Deir el-Medina, where workers praised the king’s devotion to Amun. Even after promoting a variety of cults, Ramesses reaffirmed Amun’s primacy as King of the Gods.

The impact of Ramesses II’s religious policies was a flowering of traditional Egyptian religion and monumental worship. By the end of his reign, Egypt was filled with new or restored temples, where daily rituals to the Gods were carried out without interruption. This recommitment helped erase the last vestiges of the Amarna Period’s communist policies.

RAMESSEUM

The Ramesseum was the memorial temple dedicated to the great Pharaoh near Luxor. The temple, oriented northwest to southeast, consisted of two massive stone pylons, each about 60 meters wide, positioned one after the other, each opening into its own courtyard. Beyond the second courtyard stood a covered hypostyle hall with 48 columns surrounding the inner sanctuary at the complex's center. A huge pylon stood in front of the first courtyard, flanked by the royal palace to the left and overshadowed at the rear by an immense statue of the king.

Pylons and outer walls were adorned with reliefs celebrating the pharaoh's military victories and emphasizing his devotion to and relationship with the Gods. Notably, scenes depicting the mighty Pharaoh and his army pursuing the retreating Hittite forces at the Battle of Kadesh, drawn from the Epic Poem of Pentaur, remain visible on the pylon today.

The Hypostyle Hall in particular is remarkable, supported by 48 massive stone columns arranged in systematic rows, creating an awe-inspiring interior almost reminiscent of an imposing forest. These columns were carefully aligned to support an immense roof structure.

Originally, the hall would have been covered with heavy stone roofing slabs, limiting natural light to strategically placed clerestory windows or openings at the upper levels, creating an atmospheric interplay of shadows and beams of light that emphasized the sacredness and mystery of the interior space.

ABU SIMBEL

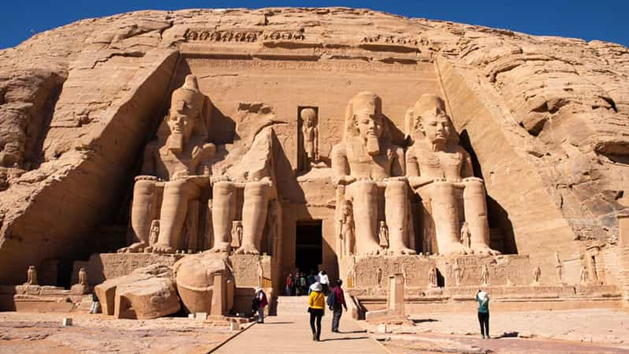

Abu Simbel is a legendary complex of temples in Nubia, carved as rock reliefs that stand as one of the most impressive symbols of Egyptian civilization.

It consists of the Great Temple, dedicated to Ramesses himself, and the Small Temple, consecrated to Hathor and Ramesses’ Great Royal Wife, Nefertari, showing his high esteem for her in all things.

The façade of the Great Temple is dominated by four immense seated statues of Ramesses II, each approximately 20 meters (66 feet) in height, projecting power and divine majesty. Between and around these colossal figures are smaller statues of Ramesses' family members, including Nefertari, his mother Tuya, and several of his children.

The innermost sanctuary contains statues of Ramesses II seated alongside three primary deities (Amun-Ra, Ra-Horakhty, and Ptah). Twice a year, on approximately February 22 and October 22, a remarkable solar alignment occurs: sunlight penetrates the temple at sunrise, illuminating the statues of Ramesses II, Amun, and Ra-Horakhty, while leaving Ptah, the god associated with darkness, in shadow. This phenomenon reflects profound design principles interlaced with astronomical precision.

Walls inside the temple display detailed reliefs recounting the Pharaoh's military triumphs, especially scenes from the Battle of Kadesh and his Nubian campaigns, as well as religious rituals demonstrating Ramesses II’s close relationship with the Gods.

For discussion of the Small Temple, please consult the article on Nefertari.

PATRON OF ART

Ramesses II was an active patron of the arts, using culture as a means of royal propaganda while also leaving behind works of enduring aesthetic value. Most characteristic of his reign are the colossal statues erected at Thebes and Abu Simbel, which continue to inspire modern works. Ramesses understood that artistic and martial projects could be integrated rather than stand in opposition.

The ruler wished it to be known that all patronage of artists was due to his benevolence. He insisted that his cartouche and name be carved deeply into stone, making them more durable and visually striking in bright sunlight.

Art from his reign set a stylistic trend that continued through the 19th and 20th Dynasties. His grandiose and preferred style, colossal scale, crowded relief compositions filled with action, and bombastic inscriptions, became the norm for later rulers who tried to emulate his greatness. His reputation as a patron of culture persisted. Even during the often lackluster times after his dynasty, being linked to Ramesses’ line was an honor.

Ramesses II’s reign also encouraged literary works and scribal culture. The most famous literary piece from his time is the Poem of Pentaur, an epic poem recounting the Battle of Kadesh from the Egyptian perspective. This text is often considered one of the earliest examples of historical epic poetry.

It was inscribed on temple walls and likely recited by scribes, a convergence of literature, war, and monument. Other inscriptions, like the “Bulletin” (a shorter report of the Kadesh campaign), marriage stelae, and countless dedication texts, kept scribes and scholars busy. Indeed, the village of Deir el-Medina, home to the craftsmen of the royal tombs, thrived during Ramesses II’s time. Many ostraca (pottery fragments with writing) from Year 28 of his reign indicate a literate working community praising the king’s piety and leadership.

Other Egyptian rulers attempted to emulate his style of rule by becoming great patrons of religion and art, most famously Cleopatra VII Theopator and her ancestor Ptolemy.

LEGACY OF RAMESSES II

His reign lasted an extraordinary 66 years, one of the longest in Egyptian history, and his impact was so profound that later generations saw him as a semi-divine ancestor. Nine pharaohs of the 20th Dynasty were named Ramesses, directly copying his model of kingship. His mortuary cult endured for centuries.

Long into the Hellenistic and Roman periods, the monuments he had built remained as sites for tourist activity. The immense structures were a curiosity for the denizens of antiquity:

In front of the temple is a statue of the seated king, which, though made from a single stone, is so large that its greatness surpasses description.

The locals call it the Statue of Osymandyas.3

The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley immortalized Ramesses in the poem Ozymandias as a symbol of eternal imperial power:

My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

It is not shocking that Ramesses represents much of the composite Pharaoh of the Book of Exodus in Jewish tradition. The intent of this subversive work is to show that the lowliest patriarch of theirs is “greater than” the Egyptian Pharaoh. Other references in the Bible lament that Jews were put to work in Pi-Ramesses long after the death of the Pharaoh.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Kadesh Poem

2Inscription at Beit al-Wali

3Book 1, Bibliotheca Historica, Diodorus

Ramesses: Egypt’s Greatest Pharaoh, Joyce Tyldesley

The Culture of Ancient Egypt, John A. Wilson

Ramses II, Britannica

Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II, K.A. Kitchen

CREDIT

[TG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe