Sappho

Great Lyric Poetess

Sappho is known as the ‘lyric poetess’ of Ancient Greece, one of the nine Lyric Poets of Hellenic civilization. Today, her name endures from the ancient era as one of the most famous poets to ever exist. In the modern era, she has become an emblem of sexual liberation due to the erotically charged nature of some of her poems, to the point that her home island of Lesbos has become synonymous with the orientation. However, this emphasis alone downplays the fact that she was also a capable priestess of Aphrodite, patron of all women and girls, and a notable figure of independence.

Many of her poems are also underlined by displays of extreme piety, revealing her role as a priestess of the Gods.

JEWEL OF THE AEGEAN

She was born to an aristocratic and mercantile family that hailed from Mytilene, the political and cultural center of Lesbos.

Her family’s wealth came from Lesbos’ thriving wine trade, as later commentators suggested. One brother was a wine merchant in Egypt, and another served as a cupbearer in the city’s public hall. The role of cupbearer (wine-pourer) was a prestigious office reserved for youths of noble birth, confirming that Sappho belonged to the Lesbian aristocracy. Sappho and her brothers Erigyius, Larichus, and Charaxus achieved positions of high standing.

Her mother, Cleïs, was an educated woman who ensured her daughter’s talents would be recognized. It is clear that her father, Scamander, also gave the inquisitive girl an excellent education, which she put to rigorous use throughout her life.

BANISHMENT TO SYRACUSE

Sappho’s life unfolded against a backdrop of political turbulence in Lesbos. In her era (late 7th–early 6th century BC), Mytilene was ruled by contending aristocratic clans and occasionally by tyrants who seized power amid factional strife. Sappho’s family, being aristocratic, was almost certainly embroiled in these conflicts.

One such power struggle involved a tyrant named Myrsilos and, later, the famous statesman Pittacus. Her contemporary, the poet Alcaeus, writes bitterly of Myrsilos (even celebrating that tyrant’s death in a surviving fragment) and speaks of exile when his faction lost power.

It appears Sappho’s family aligned with the same political faction as Alcaeus, a faction opposed to Myrsilos. One account specifies that she went to the Sicilian city of Syracuse, which is plausible given later interest in her by the denizens of that city.

During this time, she had a daughter, also named Cleïs. Sappho did not rigidly adhere to the standards of the time in relationships.

POETICAL FOCUS

Her poetry consists of at least tens of thousands of lines. As a priestess of Aphrodite, she is best known for her love poetry; other themes in the surviving fragments of her work include family and religion. She probably wrote poetry for both individual and choral performance. Most of her best-known and best-preserved fragments explore personal emotions and were likely composed for solo performance. Her works are known for their clarity of language, vivid imagery, and immediacy.

She is one of the first known poets to elaborate from a highly individual perspective. The pronoun ‘I’ appears frequently in her works, giving a deeply personal feeling to her verses. Emotive language is one of the hallmarks of her syntax: she often uses verbal expressions and adverbs to convey the effect of others and the environment on her emotional state. This is perhaps one of the reasons she is such a popular poet in modern times, as she prefigures the introspective style of literature and poetry that became popular in the 19th century.

Much of her work also features vivid and ebullient descriptions of nature, a parallel to the kind of ultimate beauty she saw in the design of the world, and through which the Queen Mother conveyed mysteries to her:

Come hither to me, from Crete to this holy temple,

Where there is a joyful grove of apple trees,

Where altars smoke with sweet frankincense.

Therein, cool water babbles softly

Through apple branches, and the whole place

Is shaded with roses, and from shimmering leaves

A sleep of enchantment drifts down…

Here, a meadow grazed by horses blooms

With spring flowers, and the winds blow

Gently and sweetly [...]

There you, Cypris [Aphrodite], delicately pouring

Nectar intermingling with festivities

Into golden cups,

Pour it out like wine.1

Sappho is regarded as offering one of the most uniquely feminine perspectives in the art. Much of her corpus focuses on the identity of women, as she sought to express facets of this world artistically, in line with her worship of the Great Goddess. Odes to Aphrodite characterize much of her work:

ποικιλόθρον᾿ ἀθανάτ᾿ Αφρόδιτα,

παῖ Δίος δολόπλοκε, λίσσομαί σε,

μή μ᾿ ἄσαισι μηδ᾿ ὀνίαισι δάμνα,

πότνια, θῦμον,

ἀλλὰ τυίδ᾿ ἔλθ᾿, αἴ ποτα κἀτέρωτα

τὰς ἔμας αὔδας ἀίοισα πήλοι

ἔκλυες, πάτρος δὲ δόμον λίποισα

χρύσιον ἦλθες

Ornate-throned immortal Aphrodite,

wile-weaving child of Zeus, I entreat you:

do not overpower my heart,

with pain or sorrow, mistress,

but come here, if ever before,

hearing my voice from afar,

you left your father's golden house

to come to me.2

As one of the greatly revered Nine Lyric Poets, those selected for study by the scholars of Alexandria in the Hellenistic era, Sappho accumulated high status among writers. Strabo named her "the marvellous," Antipater of Sidon called her "the eternal [living] Muse," and Cicero bemoaned the theft of a statue of her from the town hall of Syracuse. Ausonius, Catullus, and many others reference Sappho; her works are commonly studied in poetic style guides and grammatical compilations from the classical period.

The theme of love is one of the most encompassing in her works. One poem compares a man she is struck by in handsomeness to the presence of a god (Fragment 31), while another (Fragment 94) mourns the parting of a woman she loves to the point that it makes her wish for death. Some of her poems praise the value of marriage and the transition of a girl to that stage of life, while others focus more on casual romance.

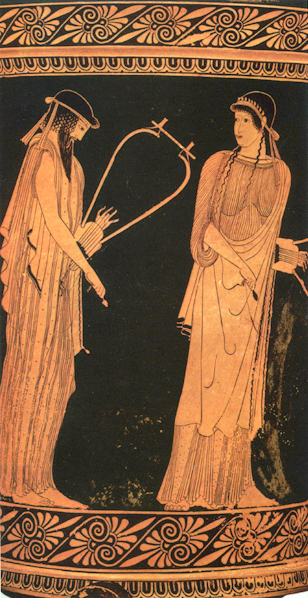

Apparently, as a musician committed to the Aphrodisiac Rites, Sappho was the inventor of the plectrum for the kithara or lyre. She wrote nine books of lyric poems, and also composed epigrams, elegiacs, iambics, and solo songs. Plutarch noted that she was a major wit and records some of her sayings.

Although her contemporary Alcaeus invented the so-called "Sapphic stanza," it came to bear her name because she used it more frequently and effectively than he did.

Many of her poems survive only in extremely fragmented form. One modern excuse is that the Aeolic dialect of Sappho discouraged audiences from writing down her works. However, this does not seem borne out by evidence of her stature in Classical Civilization, and even when her dialect was considered strange, it never impeded her reputation. The Church certainly found her works irredeemable, not simply because of their erotic content, but because of their focus on the characteristics of Goddesses and the inner life of women as a whole.

Maximus of Tyre compares Sappho to Socrates in several ways, suggesting that she may have elaborated certain aspects of philosophy.

PRIESTESS OF APHRODITE

Sappho led a notable group of young women, a fact that is both attested and interpreted. Ancient evidence, including the names of companions and the Suda’s note on her “students”, supports that she had a following of women.

What modern scholars debate is the character of that group. Earlier 20th-century scholars often leaned toward the idea of a formal school or academy, emphasizing an instructional environment. However, such interpretations have been distorted by failing to view Sappho through the lens of her actual role, which was a religious one, oriented around a thíasos or mystical circle, also dedicated to the Muses.

In line with her role as a priestess on Lesbos, her poems often refer to Eros, the God of Love and Union. Sappho also calls upon Artemis numerous times in her poetry, showing her devotion to this aspect of the Goddess. References to Zeus highlight his divine role as the arbiter of fate and destiny.

LEGACY

Sappho is possibly one of the most famous grandees of Antiquity, despite the fragmentary state of her surviving works compared to other poets. Much like Rumi, the themes of love and desire provide a vivid flashpoint for the cultivation and elevation of human longing. Unfortunately, however, narrow-minded individuals in academic departments often choose to obsess over her romantic vocation to the exclusion of how multidimensional and revolutionary she truly was.

Her commitment to the Gods was total, and her reputation was cherished in part because of that deep and profound devotion, which she spared no effort to cultivate. One final example from the poets is her voice speaking from her metaphorical tomb, an attestation to her eternal grandeur. It reads:

As you pass the Aeolian tomb, stranger, do not say that I, the Mytilenaean poetess, am dead: human hands built this, and such works of men disappear into swift oblivion; but if you judge me by the divine Muses, from each of whom I set a flower beside my nine, you will know that I escaped the gloom of Hades, and that no day will ever dawn that does not speak the name of Sappho, the lyric poetess.3

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Fragment 2, Sappho

2Ode to Aphrodite, Sappho

3Palatine Anthology, Tullius Laurea

Fragments of various poetry, Sappho

Grammar, Marius Victorinus

Speech against Verres, Cicero

Geography, Strabo

Sappho and Her Influence, David M. Robinson

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe