Senusret III

Great Pharaoh

Senusret III was the unifier of the Egyptian government and one of Egypt's greatest pharaohs. He solidified his rule, much like Ramesses would later, by conquering the eastern and southern frontiers of Egypt. His reign is widely considered the zenith of the Middle Kingdom, marked by great military prowess and sweeping internal change.

He was even deified during his lifetime, a rare honor reflecting the esteem in which he was held.

CAMPAIGN IN NUBIA

Senusret III is best known for a series of aggressive military campaigns in Nubia that dramatically expanded Egypt’s southern frontier. According to Egyptian records, he led at least four major expeditions against Nubia during his reign, notably in his sixth, eighth, tenth, and sixteenth years of rule.

These campaigns were meticulously planned. Senusret advanced methodically up the Nile instead of using lightning tactics. He secured strongpoints as he went and constructed a chain of mud-brick fortresses at strategic choke points, which he garrisoned to control river travel and supply lines as his army pushed further south.

Major forts erected under Senusret III include twin fortresses on opposite banks of the Nile at Semna and Kumma, as well as strongholds at Buhen, Uronarti, Shalfak, Askut, and others guarding

the Second Cataract region.

This network of forts created a new fixed border at Semna, beyond which Nubian peoples could not pass freely. The forts regulated immigration, enforced customs on trade, and served as bases for further military operations. The strategic impact was immense: Egypt gained secure access to Nubia’s rich resources, gold mines, gemstones, ivory, cattle, and trade routes from deeper Africa, while blocking potential Nubian incursions.

After the victories in Nubia, he boasted that he had “made safe the southern frontier.” Threats of residual raids into Egypt disappeared from the record for at least a century and a half.

CAMPAIGN IN SYRIA

In addition to his southern campaigns, Senusret III also extended Egypt’s influence into the Levant. While no Egyptian king of the Middle Kingdom established permanent rule in Asia, a

remarkable inscription known as the Sebek-khu Stele provides evidence of Senusret III’s foray into that region. The stele is dated to his reign and describes an expedition against an Asiatic

enemy. It reads:

Sebek-khu Stele

His Majesty proceeded northward to overthrow the Asiatics. His Majesty reached a foreign country of which the name was Sekmem… Then Sekmem fell, together with the wretched Retenu.

“Retenu” (or Retjenu) was the Egyptian term for Syria/Canaan, and Sekmem is thought to refer to Shechem in central Canaan. Thus, the Sebek-khu inscription records the earliest known Egyptian

campaign in the Levant, indicating that Senusret III’s army marched into Canaanite territory and sacked a local fortress or town. This victory in Palestine demonstrates the broad reach of

Senusret’s military ambition: Egypt’s armies could project power into Asia.

By extending Egypt’s borders in all directions, south into Nubia, northeast into Canaan, and diplomatically west toward Libya, Senusret III ensured Egypt’s security and enhanced its international prestige. Later generations of Egyptians cast him as a conqueror and warrior who expanded the realm to an unprecedented scale.

REFORMS OF STATE

Senusret III implemented radical internal reforms that transformed Egypt’s governance. He inherited a kingdom where powerful nomarchs (regional governors) had long held semi-autonomous sway

over the provinces (nomes).

These local dynasties dated back to the First Intermediate Period, and even by Senusret’s reign, they retained substantial authority. Due to their potential for rebellion, they represented a threat to royal unity. Senusret III saw the independent power of the nomarchs as incompatible with Ma’at, the Egyptian ideal of harmony and centralized order under the Pharaoh. It is clear Senusret was determined to show himself as a divine presence. In his view, Egypt could not be truly unified if provincial nobles were strong enough to act on their own whims. Thus, to restore the Law of Ma’at and tighten royal control, he took unprecedented steps to curb and eliminate the power of the nomarchs.

The king’s solution was a thorough administrative reorganization of Egypt. Senusret III “redistricted” the country to decrease the number of nomes, naturally reducing the number of nomarchs. He divided Egypt into just three large districts: one encompassing Lower Egypt, one for Upper Egypt, and a third comprising Nubia. He abolished many of the traditional nome jurisdictions. Each of these super-provinces was placed under the supervision of a council of officials appointed by the king, who in turn reported directly to the vizier. The effect was to sideline the hereditary nomarch families, stripping them of independent authority.

Notably, this drastic reform seems to have provoked no recorded unrest. Surviving inscriptions in the tombs of former nomarchs suggest that many were given roles in the new administration and remained proud to serve the king. The Pharaoh’s prestige and wisdom ensured that the dismantling of regional power was accepted without rebellion.

Therefore, the impact of Senusret III’s centralization was far-reaching. In his effort to remake Egypt into a tightly controlled divine realm, he created a much stronger and more secure central government. Resources that were once diverted into the hands of provincial lords now flowed to the royal treasury. Senusret ensured the provincial militias that nomarchs once commanded were disbanded and absorbed into the Pharaoh’s central state army, eliminating any military base for local dissent.

SOCIAL CHANGE

With regional tax revenues and labor now firmly under royal control, the crown’s wealth increased significantly. One unexpected social outcome of these changes was the rise of a new “middle class” and meritocracy in Egypt.

More people were now working in higher-paying jobs as administrators and bureaucrats, which enriched the individual nomes and provided a greater amount of disposable income. The resulting stability and affluence encouraged patronage of the arts and the building of elaborate personal tombs, fueling a renaissance in craftsmanship and culture.

In short, Senusret III’s administrative reforms not

only tightened royal authority over a once-fractious land, but also helped create a more meritocratic bureaucracy and a prosperous, well-integrated society. Later Middle Kingdom rulers

continued on the path he set. By the end of the 12th Dynasty, the era of powerful nomarchs was definitively over. All important decisions and resources were now in “the hands of the

king,” as

Senusret intended. This centralized model of governance would endure into the New Kingdom, setting the stage for Egypt’s functioning as a unified empire.

MASON OF EGYPT

Senusret III was an active builder, commissioning numerous construction projects that demonstrated his piety to the Gods. He undertook works across the country, from the Nile Delta to Nubia, including temples, fortifications, and an impressive royal tomb complex. Monumental architecture ensured the deeds of the Pharaoh would be recorded in stone and brick forever.

In keeping with Pharaonic tradition, Senusret III built a pyramid. He broke from the recent custom of his 12th Dynasty predecessors, who built near the capital Itj-Tawy, since Senusret chose to locate his pyramid at Dahshur, an area just south of Memphis where Old Kingdom Pharaohs like Sneferu had erected their great pyramids.

Situating his monument near the venerable pyramids of the 4th Dynasty, Senusret was deliberately aligning himself with the glorious past. His pyramid, known today as the Pyramid of Senusret III, was one of the largest of the Middle Kingdom. Originally, it rose to an estimated height of about 78 meters, making it “the most impressive Middle Kingdom pyramid” in scale.

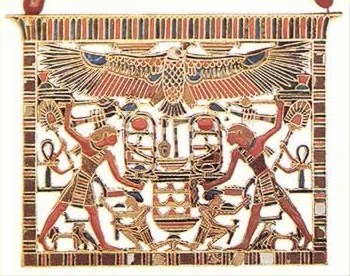

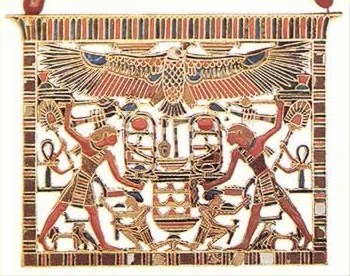

Tomb object

Unlike the solid stone pyramids of the Old Kingdom, however, Senusret’s pyramid was constructed with a core of mud bricks faced with fine Tura limestone. Over time, the limestone casing was stripped, and the mud-brick core has eroded, leaving only a low mound today.

Nonetheless, excavations have revealed the pyramid’s complex design. It featured a square perimeter wall with niched façades and an extensive substructure of corridors, chambers, and a granite-lined burial vault. In the vicinity, he built a mortuary temple and seven smaller pyramids for his royal wives and daughters, indicating a whole royal cemetery at Dahshur. Treasures from the tombs of these princesses, such as the famous jewelry of Senusret’s daughter Sithathoriunet, attest to the wealth of his court.

The military fortresses that Senusret III built in Nubia stand as a unique class of monuments, blending military and civil engineering. Huge mud-brick walls of five-meter thickness with bastions, trenches, and drawbridges made them virtually impregnable for their time. Inside, they housed temples, granaries, armories, and barracks, constituting effectively self-sufficient outposts. Forts like Buhen (with its towering walls) and Uronarti (on an island commanding the Nile channel) marveled in their design. The fortress of Uronarti even bore an evocative name: Djer-Setiu (“Repelling the Asiatics”), highlighting its dual role in guarding against both Nubian and other foreign enemies.

Notably, he excavated a navigable canal through the First Cataract of the Nile. The First Cataract at Aswan had long been an obstacle to shipping, requiring cargo to be portaged around the

rapids. Senusret’s project cleared or enlarged a channel to allow easier passage for boats, facilitating trade and troop movements between Lower Egypt and Nubia. An inscription by the Pharaoh

on Sehel Island near Aswan commemorates this feat.

MASON OF THE GODS

Senusret III invested in the expansion and embellishment of several important cult temples. In Thebes, he made additions to the great Temple of Amun at Karnak, continuing a 12th Dynasty

tradition of elevating Amun’s sanctuary.

He also built or expanded a temple to Montu, the Theban war-God, at Medamud (just north of Thebes). This emphasis on Montu elaborated Senusret’s military might, essentially pairing his rule with the patron deity of victorious war. In inscriptions, Senusret sometimes took the epithet “Beloved of Montu,” linking his victories to this God.

Farther north, at Abydos, Senusret III undertook a significant project that served both religious and funerary purposes: he established an entire temple-town complex near the sacred city.

Archaeological findings show that he built a fortified town called Wah-Sut (“Enduring-are-the-Places-of-[Senusret]”). It was complete with a palace, administrative buildings, and a temple for his royal cult.

Hidden in the bedrock nearby, he excavated a large subterranean tomb (often termed his Abydos cenotaph), where some scholars believe he intended to be interred to unite with the cult of Osiris, lord of the underworld.

Senusret III’s building projects display a balance between statecraft and piety: he honored the Gods (Amun, Montu, Osiris) and in turn bolstered the ideological foundation of his rule.

These were a physical manifestation of Senusret’s policy to secure Egypt’s borders with unassailable strongholds. Their remains, excavated by archaeologists before being flooded by Lake Nasser, revealed careful town planning and coordination, all achieved by Senusret’s administration nearly 3,800 years ago. In summary, Senusret III’s monuments, from pyramids and temples to canals and fortresses, collectively illustrate a reign that was architecturally ambitious and ideologically charged. Each project reinforced his image as a king who could build as grandly as he could conquer, and who left Egypt more protected and devout than he found it.

RELIGIOUS POLICY

Religion and kingship were inseparable in ancient Egypt, and Senusret III took deliberate steps to elevate his divine standing and align himself with powerful religious traditions. One notable aspect of his reign is that Senusret III was deified while still alive, an extraordinary honor for a pharaoh. The Egyptians established an official cult for the living king, worshipping him as a god, something only a handful of pharaohs ever received in their lifetime.

Senusret III’s subjects regarded him with an almost unprecedented reverence. He was venerated especially in Nubia, where later generations maintained temples and offerings to him. At

the fortress of Semna, evidence shows Senusret III was worshipped as a local deity for centuries after his death.

This may reflect the deep impact he had in that region; having been the conqueror and “protector” of the southern frontier, he became a patron figure in the eyes of those who lived there. In Abydos too, his funerary cult persisted long after his reign, and the town and temple he built at Abydos became a locus of continued royal commemoration. That his cult “operated at the same level” as those of the Gods while he lived implies that state religion under Senusret III strongly emphasized the pharaoh’s divine role. Statues and stelae depict him making offerings to deities like Amun and Osiris, but also receiving worship himself.

Senusret III’s religious policy can be inferred from his building programs and inscriptions. His augmentation of Amun’s temple at Karnak indicates support for the Amun priesthood, which was rising in prominence at Thebes. By honoring Amun, Senusret bolstered the theology that the king is the earthly agent of Amun-Ra, legitimizing his rule via the chief state God. His temple to Montu (the war-God) likewise reinforced the idea that the pharaoh was the champion of Egypt’s armies under divine aegis. In inscriptions, Senusret sometimes took the epithet “Beloved of Montu,” linking his victories.

ARTISTIC PATRON

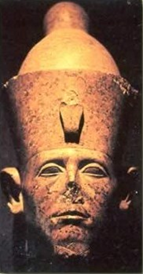

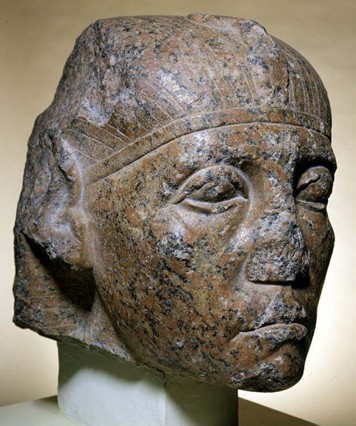

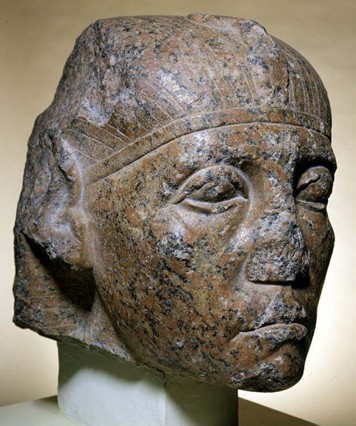

Granite head from a sphinx of Senusret III, wearing the royal nemes headdress

The art of Senusret III’s reign is especially remarkable for its innovations in royal portraiture.

Ancient Egyptian art generally portrayed pharaohs in an idealized, eternally youthful form, but Senusret III broke this convention in striking ways. Many of his statues and sphinxes show the

king with an unprecedented level of realism and emotional expression. In a series of sculptures likely created at different times in his life, Senusret is depicted from vigorous youth through

to mature adulthood. Early portraits show him with a confident, perhaps even slight smile, but his most famous statues present a starkly aged and careworn visage. The king’s face in these

later works has heavy eyelids, lines etched around the nose and mouth, and a somber, almost brooding expression.

He appears as a man burdened by responsibility, showing a stoic image of rulership as arduous service. This realism was the dominant style of Middle Kingdom art pushed by his patronage.

Senusret III’s sculptures stand as prime exemplars. One statue from the Egyptian Museum shows him with a furrowed brow and downturned lips, conveying determination. Another, the so-called

“Berlin head” of Senusret III, is especially haunting with its deeply lined face and drooping features that make the king look older than his years.

Egyptian royal art had not yet presented the Pharaoh in such a human yet authoritative manner. As one historian notes, “never before… had a king so honestly represented

his own mortal aspect

for effect.”

This blend of realism in royal portraiture and traditional symbolism in royal regalia illustrates the unique artistic legacy of Senusret III’s era. Middle Kingdom artists reached new heights of technical skill and expressive content under his patronage, prefiguring Classical Greek styles later on. The combination of austere imagery with humanizing realism made Senusret III’s likeness instantly recognizable. So esteemed were these representations that in later periods, pharaohs of the New Kingdom such as Thutmose III admired and perhaps emulated Senusret’s portrayals to evoke his enduring aura.

The reign of Senusret III was a royal era in which Pharaonic power was reasserted with vigor, the state was reformed, and Egypt’s artistic and architectural legacy was fastened into place with enduring peace. His epithet Khakaure (“Appearing like the souls of Re”) proved fitting. Senusret III as Pharaoh shined with the radiance of a visionary ruler who transformed his country.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ancient Egyptian stelae and texts from Senusret III’s reign, including the Semna boundary stelae and the Sebek-khu Stele.

Archaeological and historical analyses by Egyptologists (e.g. J. Wegner, D. Silverman) on Senusret III’s campaigns, forts, and Abydos complex.

Senusret III, World History Encyclopedia, J. Mark,

How Did Senusret III Influence Ancient Egyptian History, DailyHistory.org

Retrospect Journal on Second Cataract forts and studies of Middle Kingdom texts (PMC article on Senusret III’s portraiture)

CREDIT:

[TG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe