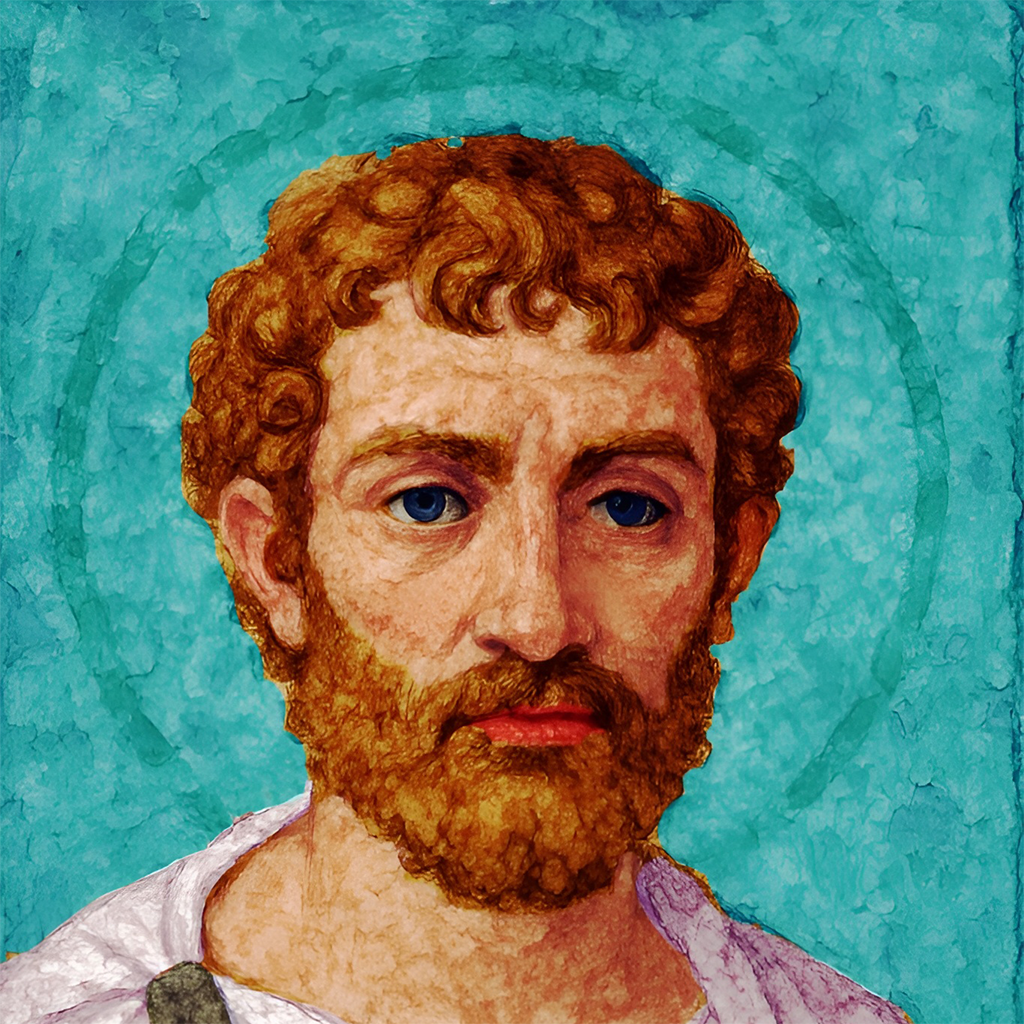

Symmachus

Keeper of Religion

Quintus Aurelius Symmachus (c. 345–402 CE) stands among the final great standard-bearers of Rome's senatorial aristocratic tradition and of its ancient religious traditions. As an orator, statesman, and letter writer at the very moment Christianity became the dominant force in imperial culture and administration, Symmachus championed the original Pagan religion of Rome in a public forum and on the Senate floor, ultimately crafting one of the greatest defenses of toleration and the rights of old religion in the historical record of late antiquity.

Symmachus's career coincided with the era in which the ancient world of traditional cults collided with the ascendant Christian empire. The campaign for the restoration of the Altar of Victory in the Senate, his appeals to emperors Gratian and Valentinian II, and his confrontation with Bishop Ambrose of Milan became the defining episode in the 'struggle of the altars'—a last, eloquent defiance against the Christianization of Roman public life.

EARLY LIFE AND ARISTOCRATIC ROOTS

Symmachus was born circa 345 into the uppermost echelons of Rome's senatorial aristocracy. He was the son of Lucius Aurelius Avianius Symmachus, himself a twice-serving urban prefect (effectively a city magistrate) of Rome and a stalwart of the Pagan conservative elite. Symmachus's mother, though her name has not survived, was the daughter of Fabius Tatianus, a consul in 337 and also a two-term urban prefect themselves. Symmachus had two brothers, both provincial governors (consulares), and a sister, whose marriage is believed to have allied the Symmachi family with the influential and increasingly Christian Anicii line, thus entwining Symmachus's heritage with both Pagan and Christian networks, and likely affording him deeper knowledge of Christianity's spread among Rome's aristocracy.

Raised in a world of immense wealth and refined tradition, Symmachus pursued his education in Gaul (typically considered in either modern Bordeaux or Toulouse), a region with a then thriving intellectual scene despite its own increasing Christianization. It was during this period that he formed an enduring friendship with the poet and statesman Ausonius, who would be the tutor of future Emperor Gratian, who would also remain an important correspondent and intellectual influence.

He would go on to marry Rusticiana, daughter of Memmius Vitrasius Orfitus, another twice urban prefect, and Constantina of the Constantinian dynasty. They would have two children, one of which would continue Symmachus' own dedication to the old religion by building a Temple to Flora, Goddess of Spring, in Rome.

EARLY OFFICE

Symmachus's ascent through the cursus honorum (course of honores), the time-honored sequence of Roman political and religious offices, reflected not only his family's prominence but also his personal gifts. He held the offices of quaestor and praetor at a young age before being appointed Corrector of Lucania and the Bruttii in 365. Around this time, family connections likely facilitated his induction to the priestly College of Pontiffs, specifically as a pontifex of Vesta, a post he retained for life and which anchored his ritual role in the increasingly fading world of Roman public cults.

In 367–368, Symmachus joined a senatorial embassy to the imperial court at Trier to celebrate Emperor Valentinian I's quinquennalia, his fifth anniversary of reign. Here, he delivered three panegyrics—his earliest surviving oratorical feats—marking his emergence on the imperial stage.

By 373, his growing reputation saw him appointed as the proconsul of Africa, one of the most prestigious provincial governorships. During this tenure, he confronted the unrest sparked by the rebellion of Firmus in Mauretania (a major uprising lead by a Berber prince in North Africa), interacting directly with future Emperor Theodosius, then a military commander. Symmachus's administration appears marked by diligence, evidenced by his careful management of estates as well as the maintenance of good relations with the local elite.

In 384, Symmachus reached the apex of urban political life as urban prefect of Rome (praefectus urbi), a role that made him the city's chief magistrate and brought him—by then, as princeps senatus—to the heart of Rome's religious and civic identity. This office, awarded in part as a political balancing act by the court of Valentinian II seeking to placate disappointed Pagan senators, set the stage for his most famous intervention: the defense of Pagan public cults.

In 391, after a period of political eclipse due to his ill-fated support for usurper Magnus Maximus (discussed further below), Symmachus was rehabilitated and appointed consul, the republic's most ancient magistracy—a final crowning honor for an aristocrat regarded by peers as the embodiment of mos maiorum, or, customs of the ancestors.

PAGAN ARISTOCRACY, BELIEF AND RITUAL

Symmachus's reputation, both among allies and adversaries, was inextricably linked to the enduring, intermarried pagan aristocracy of Rome. He was not a solitary figure but a scion of a class still deeply invested in the performance of ancient rites, civic ceremonies, and the patronage of traditional learning. Along with contemporaries such as Vettius Agorius Praetextatus and Virius Nicomachus Flavianus (who married Symmachus' daughter Galla), that formed Rome's most notable Pagan circle, Symmachus led a social milieu that defined itself as the 'better part of mankind' and cultivated a nostalgic vision of Roman identity.

It should be said that the scope of Symmachus's wealth was notable even among the aristocracy. He maintained a mansion on Rome's Caelian Hill, several city properties, over a dozen villas across Italy, and extensive estates in Sicily and Mauretania. His vast resources enabled him to stage lavish public games, but more importantly, fulfill the expectations of his office as patron and priest. His property, the Domus Symmachorum, became a symbol of senatorial grandeur and the focus for the delivery of his correspondence and the performance of his domestic religious duties.

Symmachus's religious outlook was shaped by the tria genera theologiae—a classical division of divine study into mythical, physical, and civic theology. While myth and philosophy interested him, Symmachus most clearly embodied the theologia civilis or sacra publica, the practical, civic enactment of religion which underpinned Roman legal, social, and state identity.

He was meticulous as a priest of Vesta, upholding rituals with scrupulous care. Letters in his corpus describe his participation in the Vestalia festival and his enforcement of vestal discipline. In one letter, he prays: "O gods of our native land, pardon us for neglecting your rites!" expressing both his belief in Rome's traditional cult and anxiety over the neglect of ritual under Christian emperors. The cult of Vesta (regarded by the Romans as the Greek Hestia, Goddess of the hearth, home, family and sacred fire) were indeed a sacred part of Rome's religious rites, and Symmachus' anxieties were in accordance to his belief as a priest of Vesta. Once a year, the Vestal virgins gave the Rex Sacrorum (Rome's most important priest next to the Pontifex Maximus) a ritualized warning to remain vigilant in his duties, lest Rome lose its very contact with the Gods.

For Symmachus, it seemed, ritualistic duty was his utmost priority, and its dereliction among Rome's populace, was one of his greatest woes.

His statements are pervaded by a sense of regret for the passing of the old ways, including the poignant:

"Me paenitet tempora moresque transuisse" - "I regret that times and customs have changed."

THE ALTAR OF VICTORY CONTROVERSY

The "Altar of Victory" episode stands as the most significant and public confrontation between the pagan senatorial order and the Christianization of the empire. In 382, Emperor Gratian, himself a Christian and influenced by Bishop Ambrose, ordered the removal of the Altar of Victory (that is, the altar belonging to the winged Goddess Victoria) from the Curia (the Senate house), discontinued state sacrifices, curtailed stipends for the Vestal Virgins, and orchestrated a broader withdrawal of state patronage for traditional religion.

This removal was not merely symbolic. The altar and its votive rites were central to the conduct of Senate business, the pronouncement of vows for Rome's safety on behalf of the emperor, and the declaration of loyalty to the res publica. The implications reverberated through the entire system of Roman civic religion.

The Senate, its pagan members dismayed, selected Symmachus—then Rome's most gifted orator and a man of unimpeachable patrician standing—as their spokesman. He led a delegation to Gratian's court in Milan to plead for a reversal of the decision and the restoration of the altar and the stipends. The audience, however, was denied—the first of his setbacks.

After Gratian's assassination in 383, Symmachus again rose to advocate the old religion in the name of the Senate. Now as urban prefect, he composed his most famous document, the Third Relatio, addressed in 384 to Valentinian II (and his Eastern co-emperors Theodosius and Arcadius, although Valentinian II was the real recipient).

The Relatio III was Symmachus' rhetorical and philosophical masterstroke, blending appeals to tradition, reason, and civic utility. Symmachus argued for the restoration of the old religious order:

Relatio III, Symmachus

We demand then the restoration of that condition of religious affairs which was so long advantageous to the state... If the religion of old times does not make a precedent, let the connivance of the last [emperor] do so.

Recognizing his audience, Symmachus tried his best to appeal to even his Christian listeners, arguing for religious tolerance and the altar's restoration, suggesting that they could at least live in peace and respect.

Relatio III, Symmachus

We gaze up at the same stars; the sky covers us all; the same universe encompasses us. Does it matter what practical system we adopt in our search for the Truth? The heart of so great a mystery cannot be reached by following one road only.

Symmachus further argued that recent famines were the consequence of sacrilege—of neglecting the old Gods—and that the ancient rites, which had "preserved the empire for the divine parent of your Highnesses," ought to be upheld not only for tradition's sake but for the public good.

The Relatio ends on a plea for peace among all cults rather than confrontation, Symmachus trying his best to be the honorable, larger man even despite the extent of the Christian suppression.

Relatio III, Symmachus

We ask, then, for peace for the gods of our fathers and of our country. It is just that all worship should be considered as one... We cannot attain to so great a secret by one road; but this discussion is rather for persons at ease, we offer now prayers, not conflict.

Symmachus's appeal was swiftly and callously rejected by Bishop Ambrose of Milan, who composed two letters (Epistles 17 and 18) to Valentinian II. Ambrose twists and defiles Symmachus' plea, accuses him of idolatory, and utterly misrepresents the old religion as heathen supersitions. Ambrose argued that Christian emperors could not countenance the restoration of Paganism, dismissed the link between old rites and Rome's successes as myth despite their apparence (and despite how Rome itself was continuing to wane during this era) and insisted that the Altar of Christ alone merited restoration.

Ambrose's close relationship to the court ultimately ensured that Symmachus's request was denied. The decisive voice in imperial policy belonged increasingly to the Christian hierarchy, and the anti-Pagan edicts were continued and in some cases intensified in the following years.

POLITICAL REHABILITATION

In 387 CE, Symmachus sympathized with the usurper Magnus Maximus, who had overthrown Emperor Gratian, and was now moving upon Italy, causing Western Roman Emperor Valentian II to flee. Magnus Maximus, for his part, was well liked by the Roman army, who felt the Emperor was favoring foreigners in his forces over the native Romans. Given Symmachus' own earlier difficulties with Gratian, it could only be expected that Symmachus would find an alternative preferable.

As Senate leader, he congratulated Maximus on behalf of the Senate, a move that backfired when now Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius I defeated Maximus in 388 CE. Impeached for treason, Symmachus sought sanctuary and was pardoned after delivering an apologetic address to Theodosius, aided by influential friends.

His contrition led to rehabilitation, culminating in his appointment as consul in 391 CE alongside Eutolmius Tatianus, who had previously served as governor of Egypt. Rome's aristocracy still held power enough, even as the ancestral faith surrounding it increasingly collapsed.

After Valentian II was found hanged in his Vienne residence, a man by the name of Eugenius was elevated to Western Emperor on 22 August 392 at Lyons, by Arbogast, the magister militum who had served under Valentian II (at the request of Theodosius) and was de-facto Emperor before passing the role to Eugenius. This was, for its part, a tactical move, as Arbogast was a Frank, and Pagan, meaning his opportunities for power and influence than Eugenius, who was a Roman Christian.

Though, despite being a Christian, Eugenius was extremely Pagan sympathetic, replacing many of Theodosius' trusted men in the Western Empire with men loyal to him. Men who were often frequently Pagan. Senators convinced Eugenius to use public money to fund Pagan projects, such as the rededication of the Temple of Venus and Roma and the restoration of the Altar of Victory within the Curia, lead by Symmachus' own close friend Virius Nicomachus Flavianus, who was now praetorian prefect.

For a time, it seemed, Symmachus' hopes were coming to fruition. Symmachus' remained conservative in his outspoken support however, unlike his friend, perhaps having learned his lesson with Magnus Maximus. This would, regrettably, end up being a truly wise thing indeed, as Theodosius's final victory at the Battle of the Frigidus against Eugenius in 394 following a build up of tensions was something of a last gasp for state Paganism in Rome.

Afterwards, anti-Pagan legislation hardened, and even private and household cults were increasingly suppressed under Theodosius continued assault on the traditional religion, though thankfully for those still practicing in the Empire, he too died only several months later, having served only a brief tenure as Emperor.

LEGACY IN LETTERS, WORKS AND ART

After his consulship, Symmachus allied with Stilicho, guardian of Emperor Honorius, helping restore some Senate powers following Theodosius's death in 395 CE. The corpus of his correspondence runs to nearly 900 letters in ten books, edited and published after his death by his son, Quintus Fabius Memmius Symmachus. Mimicking the carefully composed style and social purposes of Cicero and Pliny, these letters range from ephemeral notes and recommendations to thoroughly polished missives discussing literature, festivals, familial duties, and the shadow of passing rites.

Hierarchy, friendship, and patronage—rather than confessions of inner conflict or direct religious polemic—dominate the correspondence. Yet the letters are a treasure-trove for historians of late Roman society, giving a rare look into how the last members of the Pagan nobility navigated the increasingly oppressive, Christian world.

Epistoles, 1.51 (To Praetextatus) - Symmachus laments the increasing abandonment of the traditional Roman altars:

Fuerit haec olim simplex diuinae rei delegatio: nunc aris deesse Romanos genus est ambiendi - Once this sort of delegation of religious affairs was straight forward; now to desert the altars is for Romans a kind of careerism.

The collection of Relationes as well—forty-nine surviving reports and memoranda produced in his capacity as urban prefect—are vital records of administration and civic negotiation. They include, in addition to the famous Relatio III, his daily interventions on Rome's behalf, dealing with public order, festivals, anomalies (such as prodigies and the interpretation of omens), legal cases involving the Vestals, and temple administration.

These documents, as one would expect, are quite unique for their period, offer a window into the mechanics of Rome's urban administration at the cusp of the Christian empire's solidification, as well as the last functioning manifestations of sacra publica - the public religious rites of Rome.

Though only a few fragments of his many orations survive, their content and style have drawn critical admiration, with some flatteringly comparing them to Cicero (fittingly, given the mimickry of his style) Delivered at imperial courts and before regional assemblies, these panegyrics celebrated Emperors such as Valentinian I and Gratian, and were something of an almost nostalgic celebration of virtue, military prowess, and, notably again, the restoration of ancient rites.

In one notable instance, he paints a very flattering image of Valentian I.

I feel the glow of divine light, as usually happens when the dawning sun breaks forth and the splendour of the world is revealed... Proposed at last you arose like a new star, which the ocean steeped in sacred billows raises up in renewed observance of daybreak!"

Though it may seem like excessive flattery by today's standards, this manner of complimentary syntax between respected friends and associates was almost something of a tradition in itself in Rome, especially within Symmachus' own circle, given his devotion to amicitia, which may translate simply to "friendship", but meant something far more sophisticated to Symmachus. As he himself says:

Epistoles, 7.99 (To Longinianus)

Cultum amicitiae libenter exerceo - I exercise willingly the cult of friendship.

Amusingly, and demonstrating a great amount of self-awareness, Symmachus himself offered his own thoughts on the sometimes excessive praise exchanged between friends and colleagues that often overshadowed all else.

Epistoles, 2.35.2 (to Flavianus Senior)

"Quousque enim dandae ac reddendae salutationis uerba blaterabimus, cum alia stilo materia non suppetat? - For how long are we to go chattering, giving and returning words of salutation due to the lack of anything worthwhile to write?

Symmachus was also involved in the preservation of Roman literary heritage. Notably, a letter dated to 401 discusses his work on a new edition of Livy's Ab Urbe Condita (History of Rome), and his involvement—alongside other learned nobles—in ensuring the transmission of Livy's manuscripts is attested by marginal annotations in several of the extant codices. Further, through his family's libraries and their ties to the Nicomachi, Symmachus served as a great preserver of Roman texts, something that helped transit the words of the ancients into the medieval era, which in turn, helped catalyze the Renaissance itself.

Symmachus' however, did not only leave behind literary works. Perhaps the most famous artifact linking Symmachus's world to later generations is the magnificent Symmachi–Nicomachi ivory diptych. Crafted between 388–401, likely to celebrate either a marriage between the two elite families or the elevation of a daughter to a priestly office, these panels show priestesses engaged in traditional rites—one, beneath an oak tree, sprinkles incense over the flames; the other holds torches before a round altar.

Another ivory (seen at the beginning of this article) sometimes called the "Elevation of Symmachus," features an aristocrat (almost certainly Symmachus himself) being carried up to the heavens, attended by symbols of the afterlife, eagles, and wind deities, all beneath the sun god. The inscription "Symmachorum" marks it as a tribute to the famous family, crafted in 402, seemingly to commemorate the death of Quintus Aurelius himself, as the genii lift him upwards, suggesting his apotheosis.

These artifacts stand as some of the latest examples of open Pagan art in the Roman empire, before the advent of medieval aesthetics, showing Pagan art did not simply vanish all at once, and there were those who still sought to bring the beauty of the Gods into the world.

LATER YEARS AND REPUTATION

Symmachus survived in public life under successive, now-Christian, regimes, even forming a political alliance with Stilicho, the powerful magister militum and guardian of Honorius. Despite the erosion of the Senate's and Rome's authority, Symmachus held the honorary position of princeps senatus and remained an advisor and diplomat trusted by his peers.

He continued his literary activities, including the edition of Livy and the correspondence which his son would preserve. One of his letters dates as late as 402, the year of his death at Ravenna. His obituaries, set up by his son, boasted not of imperial loyalty but of unfailing adherence to ancestral custom, public piety, and eloquence.

His image—with that of Flavianus and Praetextatus—entered the intellectual afterlife of late Roman culture, forming central characters in Macrobius's Saturnalia, a dialogue set nostalgically in the old aristocratic world.

Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, ultimately, was a defender of ancestral religion and the dignity of the senate, regarded by many as the last great Pagan of Rome, even by his opponents, with Aurelius Prudentius Clemens a fourth century Christian poet, condemning him and praising him in the same breath, calling him a shining star of Latin oratory, and suggesting he even surpassed Cicero himself.

Relatio III, Symmachus

Let me use the ancestral ceremonies, for I do not repent of them. Let me live after my own fashion, for I am free. This worship subdued the world to my laws, these sacred rites repelled Hannibal from the walls, and the Senones from the Capitol...

---

BIBILIOGRAPHY

The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus - Jillian Mitchell 2016

Prefect and Emperor; the Relationes of Symmachus, A.D. 384 - translation and notes by R.H. Barrow, 1973

"The Letters of Symmachus" in Latin Literature of the Fourth Century - J.F. Matthews, 1974

The Last Pagans of Rome - Cameron Allen, 2011

https://web.archive.org/web/20060830001333/http://www29.homepage.villanova.edu/christopher.haas/symm-ambr.htm- The Altar of Victory Controversy: full archive of Symmachus and Ambrose's discourse

CREDIT:

[NG] Arcadia

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe