Great Admiral

Themistocles

authors: NG Arcadia, Thersthara

Themistokles (524 BC - 459 BC) was a Greek statesman and military leader, particularly known for his role in Athens' resistance to the Persian invasion. His strategic acumen and military achievements made Athens a maritime power in the Greek world and played a major role in the Greek victory at the Battle of Salamis against the Persian Empire. Most of all, however, he's best known as a pivotal player in the Greco-Persian Wars, as the pioneer of Athens’ naval fleet and perhaps the most integral of all men to the ultimate Greek victory. Regardless, Themistocles faced many challenges in both his military and political career and was a complex figure.

EARLY LIFE

Unlike many of his notable contemporaries, Themistocles did not start among the elite of Athenian society. His father was a respectable, though mostly unknown figure from Attica, and his mother's identity was even more obscure, outside of the fact she may have been Thracian or from Halicarnassus. Though Greek by ethnicity, parts of Themistocles's family were metics to Athens, and they had grown up outside the city walls. This made Themistocles unpopular among the nobility, because at that time the nobility was the most powerful group that played an active role in the political arena. However, Themistokles, as a commoner, managed to gain the support of the people and thus started his political career.

Although there are not many details about his education and youth, it is known that Themistocles had a highly intelligent, ambitious and strategic mind. His family was too obscure to further his reputation or allow for immediate connections in life. However, even as a boy, Themistocles had already begun bridging the gap between himself and the more "legitimate" children of Athens. Somehow, the child had convinced the children of highborn families to join him in exercising outside Cynosarges, the gymnasium of Heracles and thus even in his youth, he began to show leadership qualities, and his capability in politics attracted attention.

Plutarch considered the poetic implication here, as Heracles was something of an "outsider" himself in Olympus, being born of a mortal, and yet having labored his way to Godhood. Further, he states it was quite apparent that Themistocles had his sights set on an important public life early. As Themistocles' own teacher stated,

"My boy, you will be nothing insignificant, but definitely something great, either for good or evil."

Themistocles’ upbringing coincided with a period of upheaval in Athens. It had only been several years before his birth that the tyrant Peisistratos had died, leading to a labyrinthine power battle involving more than one noble family and the influence of Sparta. In the end, one man outmaneuvered the rest, and that would be Cleisthenes, who established the foundation of what ultimately became Athens’ democracy. Suddenly, any man had the potential to rise in influence, and that is exactly what Themistocles set out to do.

THE RISE OF THE ADMIRAL

It was a new age of polity and bureaucracy in Athens, and Themistocles set about becoming one of the first masters of this new system. He soon moved from his original dwelling outside the city, to Ceramicus, one of Athen's down markets, that is, a market most associated with being affordable to all, contrast to the upmarkets of the elite. With this move alone, Themistocles had established himself as no ordinary politician, but a populist, a man of the people, with whom he made a point interacting with. It was a choice that could not have come at a better time, given that, in the birthing years of true democracy, it was the influence of this demographic which was set to rise. The poor were unused to being regarded in such lofty ways, and it was said Themistocles never forgot the name of a single voter.

Still, Themistocles did not go out of his way to make enemies of the aristocracy, though his study of law and service as an attorney for the good of the common people were most certainly what cemented his election as Archon Eponymous, the highest magistrate office in Athens. Immediately, Themistocles began to advocate for what would later be the shaping element of his life — the expansion of Athens’ naval power and prominence.

A new port was established in Piraeus, grander than the aging, more limited structures in the Bay of Phalerum. It was an easily fortifiable location with natural harbors, superior to Phalerum's sandy shores, and tariffs of two percent were levied against all goods passing through the port. Even in the wartime, the port proved lucrative.

Themistocles' rise on the political scene was closely linked to democratic developments in Athens carried by these lucrative developments. Within the year, Themistocles began to make strategic moves to put himself in the public eye. In Athens, he particularly distinguished himself as a politician who challenged the power of the nobility and won the support of the people. Themistocles participated in reforms that supported the development of democracy in Athens and promoted regulations that allowed for greater popular participation in politics.

In 490 BC, King Darius of Persia sent an army to subjugate the Greek city-states.

The first major battle between the Persian army and the Greeks took place at the Battle of Marathon. The Athenians, with an army under the command of Miltiades, won a victory over the Persians. Although Themistokles was not in a direct command position in this battle, he was one of the first leaders to recognize the magnitude of the Persian threat.

Moreover, his designs towards a greater naval power meant more power in the body of the common citizens, given they were precisely who would be rowing and operating the ships. It was in many ways a perfect cycle of influence, as this greater amount of power was being placed into the hands of exactly who were most loyal to Themistocles; the common man.

Themistocles path to influence and power was not without its resistances. Ostracism had recently become a landmark feature in Greek polity, and suddenly the life of an Athenian politician had become fraught with a new type of peril. Displease the people, and you would be exiled from Athens for ten years. As Themistocles support among the common people grew and grew, the aristocracy, many of whom had recently faced ostracism themselves, began to look towards one Aristides, titled the Just by his admirers.

It was said by Plutarch that this rivalry had all been but predetermined, given both Themistocles and Aristides had competed quite passionately for the attention of the same youth during their adolescence, and with Aristides now speaking for the elite class, Themistocles’ desire to further expand the Athenian navy was met with resistance from their champion. Further, Aristides personally represented the upperclass Hoplites, and had little desire for the common citizen class making up the bulk of the rowers to gain even more power than they already had.

THE PERSIAN THREAT

Still, Themistocles wasn't going to let the matter pass him by. He saw the apparent reality that the son of Persian King Darius, and his successor, Xerxes I, still had eyes for Greece, and was plotting invasion. As things stood, Athens, nor Greece as a whole, had the naval power necessary to fend off the Persian fleet.

By a stroke of immense fortune, or perhaps by Divine favor, an extremely large seam of silver was discovered at the Athenian Laurion Mines. With this newfound wealth at their disposal, Athen's two foremost politicians argued what was to be done with it. Aristides argued it should be dispersed among the people. Themistocles argued that a fleet of Triremes (that is, a type of ship that specialized in ramming capabilities).

Themistocles did not argue that the Triremes should be built to counter Persia, as he understood correctly that despite the prior invasion, the threat of a new invasion felt too distant in the minds of most any Greek. Instead, he justified the expenditure by referencing the ongoing conflict with the island of Aegina, claiming that Athens could finally end the long-running war. His motion passed easily, though only an initial hundred ships were ordered, as opposed to his desired two hundred.

Thanks to Themistokles' insistence, this silver reserve was still used to expand Athens' navy, which would play a critical role in future victories over Persia.

Naturally, tension between Themistocles and Aristides reached a fever pitch soon thereafter. In what was effectively Athens’ first referendum of the people, the vote on what politician should be ostracized next was of course down to Themistocles and Aristides. Ultimately, it was the latter who was ostracized, Themistocles retaining his support of the common man.

In Plutarch's Life of Aristides, it's stated that, on the event of the referendum, Aristides was approached by an illiterate man on the street who did not recognize who he was. The man asked him if he could vote for Aristides to be ostracized. Presumably upset, Aristides still held his tongue and asked the man if Aristides had ever wronged him. The man replied no, but he was simply irritated hearing everyone refer to him as "the Just." Aristides then went on to write his own name on the ballot to be ostracized. It was said at this point, the feud between Aristides and Themistocles had drawn to a close, and this would later be pivotal moment in both their lives.

ATHENS AND SPARTA

Indeed, by 481 BCE, the major Greek city states held a congress in what was a rare show of unity, to address the imminent invasion that threatened them all. Despite the tensions, the Greek states agreed to join forces against the invader, with Sparta and Athens at the head; the former in charge of the land defense, with the latter in charge of the naval defense.

Initially, it should be stated, the other major naval powers of Greece (particularly Aegina, given the aforementioned conflict between the two), were reluctant to pledge loyalty to an Athenian commander. Themistocles, simply being pragmatic, compromised and allowed a Spartan man, Eurybiades, to head the fleet. Sparta, however, despite the famous strength of their warriors, had little in the way of a navy, and both Plutarch and Herodotus made it plain that Eurybiades was not precisely an inspiring commander or even particularly determined one.1 2 Themistocles, it's said as such, was the real force behind the Greek navy, and this would only become more blatantly obvious as the war began in earnest.

The initial Greek plan was to block Xerxes invasion at the Vale of Tempe, a narrow gorge near the borders of Thessaly. However, King Alexander I of Macedon (Alexander the Great's great-great-grandfather), informed him there were alternate paths into Thessaly they had not accounted for, and could not defend them all. He suggested, rather, that they retreat, as Alexander I, having been loosely involved with the Persian court (but apparently still loyal to the Greek city states) was aware of the sheer size of the Persian army.

Themistocles' second idea, instead, was to prevent the Persian army from accessing southern Greece, as they would inevitably need to pass through Thermopylae to do so. This would sound familiar to most, as the Battle of Thermopylae was the famous battle of Leonidas and his 300 Spartans (covered separately in the Leonidas article). As was well known, the Spartans had their own internal division about the nature of their commitment to the war, and Themistocles had to pledge the entire Athenian army to Artemisium to prove there was an equal commitment of forces on all sides.

However, this would have only been possible if every able male in Athens manned the ships, which would leave Athens itself utterly unguarded. If this was to be the end result, the Athenians had but only one choice, and that was to abandon Athens entirely, down to every last man, woman and child.

As one would imagine, convincing the entire population of a city-state to abandon their home was no small feat, and though the

precise details are lost, it's suggested Themistocles speech to the Athenian people was one of the absolute highlights of his

career. For what he was attempting to accomplish, it could not have been anything less. As he was recorded in saying,

Themistocles once uttered - "I have two gods with me, Persuasion and Compulsion".

Though not as extreme as the Spartans when it came to concepts of valor and honor, many Athenian warriors still believed it was unbecoming to fight the enemy on anything but land. Though the Athenian navy had swelled, the ocean was still something of an alien territory to Athens of this time. To engage the enemy on the open water felt dishonorable to some. Thankfully, however, Themistocles did not entirely lack support on this matter. One such backer came in the surprising for of a young man named Cimon, an aristocrat and the son of the famous Athenian military general Miltiades, who lead their army to victory against Darius ten years earlier at the Battle of Marathon. In front of the crowd, Cimon exchanged his riding equipment for a hoplite's shield, a symbolic act which demonstrated his commitment not to fight as a cavalry knight, but as a soldier aboard Athen's new triremes.

It seemed to, that the Gods themselves had indeed rallied behind Themistocles' cause. The Athenian population was further convinced of a departure from their great city as the divine serpent of Athena had left its enclosure at the Acropolis and had not touched its food offerings. For Themistocles, this was proof enough that the Gods were telling the Athenians to leave. In the aftermath of the Battle of Salamis, to be covered shortly in greater detail, the serpent itself became the symbol of the battle, and, as some regard, of Themistocles himself in the context of it.

THE ORACLE OF DELPHI

Perhaps most important of the divine signs however, was the matter of the Oracle of Delphi. The priestess had already made it clear within the first prophecy that the Athenians should indeed abandon their homes, for Xerxes would gladly raze all of Greece to the ground. Mortified by the apparent hopelessness of this first prophecy, the Athenian messengers to the Oracle entreated her for a second.

Within this second prophecy, the priestess expanded upon the first. Some Athenians still believed they remain to protect the Acropolis even if it meant perishing in the process. Again, however, the Pythia of Apollo made it clear that leaving was the only option. Moreover, she also specified that, even in leaving, that direct conflict with Xerxes was inevitable.

Ultimately, however, the key interpretation of the full second prophecy of Themistocles, who took the Oracle's reference to built wooden walls to mean that the faith of Athens should be placed within their new fleet of triremes. As it so happened also, the Oracle's direct reference to a fated battle near Salamis would not only come to pass, but, as Themistocles interpreted it, would be cruel indeed to the enemies of Athens.

Athens, however, Themistocles noted, seemed to long for the presence of Aristides, despite them having voted to ostracize him. Perhaps the old conflict seemed trivial now, given the Persian invasion, but Themistocles did the noble thing and issued a bill, allowing Aristides to return, alongside other exiles, that they may serve Athens once again.

In 480 BC, the Persians organized a major expedition to Greece, this time under the command of King Xerxes. Xerxes had moved towards Greece with a large army in the spring of 480 BC. The Greeks formed a line of defense against the Persian army. During this period, Themistocles took command of the entire Greek navy.

Further as the Oracle had foretold, these events would then lead the fleet into Salamis, where Themistocles fully intended to manifest the priestess' words, in spite of Eurybiades once again wishing to leave, this time to Isthmus, where the Greek states were building fortifications. Beyond making good on his interpretation of the prophecy, however, Themistocles saw the strategic value in fighting at Salamis, and insisted against Eurybiades demands.

This lead to a particularly famous exchange between Themistocles and Eurybiades, that went as follows:

Themistocles, at the games those who start too soon get a caning.

Yes,

said Themistocles, but those who lag behind get no crown.

Eurybiades lifted up his staff as though to smite him, Themistocles said: "Smite, but hear me." Eurybiades was so stricken in admiration of Themistocles calmness, that he decided to hear him out after all. Though, among those on the vessel, one man said Themistocles, as an Athenian, had no right to lecture those who still had homes to lose, given he had abandoned his. Again, Themistocles spoke:

Life of Themistocles, Plutarch2

It is true, thou wretch, that we have left behind us our houses and our city walls, not deeming it meet for the sake of such lifeless things to be in subjection; but we still have a city, the greatest in Hellas, our two hundred triremes, which now are ready to aid you if you choose to be saved by them; but if you go off and betray us for the second time, straightway many a Hellene will learn that the Athenians have won for themselves a city that is free and a territory that is far better than the one they cast aside.

At this point, Eurybiades had been given enough reason to reflect, and had even become fearful that he would loose control of the fleet entirely if things continued on the same trajectory. Even Aristides, who had arrived and joined Themistocles, was swayed to his plan, despite his initial agreement with the perspective of Eurybiades. Yet again, it was up to Themistocles to strategize the Greek resistance, particularly under the pressure that, despite having quelled Eurybiades, that many of the Greek leaders still wished to abandon Salamis for Isthmus. It was under this immense pressure, that Themistocles concocted his most brilliant plan yet. Most fittingly, it's said that, in the moments of Themistocles speech to the Greek fleet prior to his creation of this plan, an owl, a sacred animal of Athena, was seen flying through the rigging of their vessel. Again, it seemed, the Gods had inspired Themistocles with a truly divine stratagem.

Themistocles plan began with a man by the name of Sicinnus, a man of Persian stock though a servant of Themistocles' household who cared and looked after his children. Sicinnus was, in Themistocles' own eyes, absolutely loyal without question. For this reason, he sent Sicinnus as his personal ambassador to Xerxes. While in his entourage, Sicinnus successfully convinced Xerxes that Themistocles had every attention of betraying the Greeks for the Persians, claiming that the Greek navy had fallen into complete disarray and was planning to flee from Salamis entirely, and that Xerxes should block the strait with some of his armada and send in the rest if he wanted to crush them, there and then.

Themistocles was aware that Xerxes wanted the war over, and fast. With the sheer numbers of his army present in Greece, supplying them was no easy task. Further, the longer he spent on the Greek agenda, the more he inevitably risked uprisings or external threats at home. Xerxes wanted a decisive, immediate victory, and believed Themistocles wholeheartedly. To him, it made sense. Athens had been captured and razed, therefore, the Athenians had nowhere to go. Thus, Themistocles pledge of loyalty would spare at least the Athenian people, whereas the rest of the Greek states would all perish under his might.

During this time, Aristides approached Themistocles in his private quarters once more. Xerxes, it seemed, had already taken the bait in full. A quadrant of his navy's best ships remained at the entry of the strait into Salamis to prevent any of the Greek ships escaping. Many more had begun to slowly surround the Greeks. Here, Themistocles, coming to respect Aristides nobility, told him of the Sicinnus matter, and beseeched him to keep the other Greek leaders from fleeing the battle as so many of them wanted, much like Eurybiades. Aristides, was in complete admiration of his apparent brilliance and agreed, readying the other leaders for battle as quickly as he could.

Indeed, when Xerxes finally arrived, he did not find a fleet in total disarray, fleeing every which way. He found the entire fleet, ready to engage. And so the Battle of Salamis begun.

BATTLE OF SALAMIS

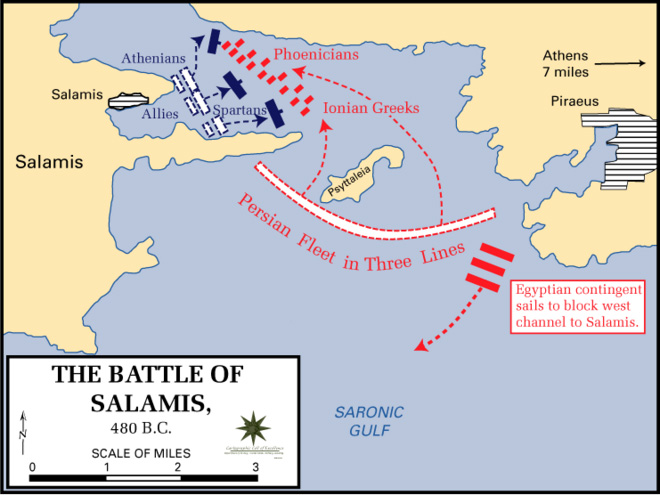

The climax of Themistocles' military strategy was the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC. The Persian army had invaded Athens and the city was largely evacuated, with the sanctuaries of the Gods and Daemons being burned by a vengeful Xerxes. As the Persians captured much of Greece, Themistocles devised a strategic plan to trap the fleet.

It was said that, as the Persian fleet approached, they could hear singing from among the Greeks.

O sons of the Greeks, go, Liberate your country, liberate Your children, your women, the seats of your fathers' gods, And the tombs of your forebears: now is the struggle for all things.

Xerxes lost his brother (a Persian admiral himself) early in the battle, as the immense size of the Persian forces became a hindrance in the narrow bays of Salamis. It is stated generally that the Greeks had anywhere between 200-300 triremes, whereas the Persian's were potentially upwards of 1200. Again, this came as a negative for the Persians. With so little space to maneuver, many of their vessels were easy pickings for the Greek triremes. Further, the Greek ships were filled with Hoplite infantry, compared to the more lightly armored soldiers aboard the average Persian trireme.

Xerxes', it was said, watched on aghast, especially at the apparently poor performance of his admirals. Artemisia, Queen of Halicarnassus, and commander of the Carian contingent of Xerxes' fleet, was said to have been under pursuit of one of the more notable Greek admirals. In the chaos, she attempted to preserve her own ship by ramming and sinking one of the other Persian vessels, tricking the Greek admiral into thinking he was actually beholding an allied ship. Xerxes, watching from a distance, and assuming Artemisia was the only individual acting boldly among his admirals, is said to have proclaimed, "My men have become women, and my women men."

In short order, the Persian fleet lost hundreds of ships. Some attempted to escape, but were then ambushed, and during the battle, a contingent lead by Aristides lead a dispatch of men to destroy Xerxes' garrison in the region.

The scope of the victory under Themistocles cannot be understated. By the impact of this battle alone, Greece was now effectively immune against Persian conquest, as they no longer had the men nor the material to take over the entire region. In one fell swoop, Greece was effectively liberated. More than anyone else's, even perhaps more than great Leonidas, the victory here was Themistocles', whose advocacy for the Athenian construction and manning of the triremes and commitment to naval warfare and to Salamis assured the greatest military victory in Greek history. As Plutarch himself wrote, "Themistocles is thought to have been the man most instrumental in achieving the salvation of Hellas."

Xerxes left Greece entirely after this defeat, though his general Mardonius remained in a foolish delusion that Greece could still be taken. Though the Persian threat remained in Greece, life began to return to some vague semblance of normality. Little transpired during the winter time, though Sparta, in a rare show of concession towards Athens (and any Athenian period), invited Themistocles in and honored him for his cleverness and stratagem. It was said during the subsequent Olympic Games, the audience cheered and gazed upon him even moreso than the actual contestants.

Athens was reclaimed and the rebuilding process started in 479 BCE, after the decisive Battle of Plataea defeated the Persian General Mardonius and ended the Persian threat in Greece practically altogether. Around this time, it is said many among the Athenian nobility had grown envious of Themistocles' achievements, though this unpopularity was short lived given his strategy in rebuilding Athens.

First and foremost, he wished to rebuild and expand upon Athens' fortifications. This would seem like a natural response to many in the here and now, given Athens' destruction. However, one must also understand the optics of the act in the context of Greece at the time. Part of Sparta's unease was understandable, given a hypothetical recapture of Athens somewhere down the line would mean an enemy fortress in an extremely tactical position. But it wasn't this that really had the Spartans concerned.

To quell this unease, Themistocles ventured to Sparta as an ambassador, to say that no fortification process was ongoing, and that they can send diplomats there to see with their own eyes. Meanwhile, Themistocles urged the Athenian builders to construct the walls as quickly as possible. By the time the diplomats arrived, Themistocles detained them for a time, allowing the builders to finish the walls before Sparta could get any word about the fortification process and attack Athens while it was weak. Again, one must understand that the Greek city stated had warred plenty, and that the unity shown during the Persian war was something of an exception rather than a rule. Persia was not even a memory by the time military tensions had arisen among the Greeks once again. Even the noble Aristides, who seemed to otherwise despise and act against trickery among fellow Greeks, aided him in the gambit.

Though this act had no consequences at the time, it did manifest a Spartan distrust of Themistocles which would later design his ultimate fate, particularly as Athens became the central power of the newly founded Delian League, which continued to fight Persia even after Sparta's resignation from the conflict.

In the meanwhile, Themistocles maintained the trend that assured the Greek victory in the first place, and expanded further on Athens' naval capabilities. The aforementioned port of Piraeus was developed further, he introduced tax breaks for merchants and artisans to attract business to Athens, and he insisted that Athens build 20 new triremes a year, to assure its continued naval dominance. Though undoubtedly a genius, Themistocles love for Athens was as such that it occasionally swayed him to callous notions, including plans to limit the other Greek states naval capabilities by destroying some of the collective war time assets. As if fate had bound them together even still, many of Themistocles more questionable decisions were kept in check by the ceaseless nobility of Aristides the Just.

Themistocles planned to draw the Persian fleet into a narrow strait. The narrow space would limit the maneuverability of the Persian ships, and the smaller and faster ships of the Greek fleet would gain the advantage. To implement this plan, he spread false information to the Persian commanders and lured them into the Salamis Strait.

The battle in the Salamis Strait ended in a victory for Themistokles. The Greek navy defeated the Persian navy in a great rout. This victory thwarted Persian plans to invade Greece and Xerxes was forced to retreat. Salamis is considered one of the most important naval victories in Greek history and Themistokles was the greatest architect of this victory.

After the victory at Salamis, Themistokles became one of Athens' most powerful leaders.

BLOSSOMING AND EXILE

Towards the end of his great decade, however, Themistocles began to accumulate enemies. Political rivals grew jealous of his influence and prestige, and Themistocles pride in his noble actions stirred claims of arrogance. Moreover, Sparta itself, now having a grudge against him due to earlier slights, was all too willing to act against him. Accusations came at him, and even though Themistocles was fairly acquitted (as the idea that Themistocles had anything to do with the alleged Spartan traitor Pausanias was laughable), it did not prevent Sparta from sponsoring rivals within Athens, including goading Cimon, who was aforementioned for his support of Themistocles during the war, to create issue with him where there was none.

In a stroke of bitter irony, it was soon after that it was Themistocles' turn to be ostracized from Greece, much as Aristides was before him. Again, one need be reminded that ostracization was not am indicator of any sort of guilt. As Plutarch put it, ostracization was "not a penalty, but a way of pacifying and alleviating that jealousy which delights to humble the eminent, breathing out its malice into this disfranchisement." In simpler terms, it was a means of avoiding needless political strife within Athens between argumentative parties. The people of Athens would have a reprieve from Themistocles presence, for better or for worse, and their anger would not have a reason to needlessly snowball.

Themistocles moved to Argos for a time. However, Sparta was not keen on letting the matter go, and rehashed the Pausanias allegations. Without the protection of Athens, there was little hope for him at this point, as Sparta wished for him to be tried by a congress of the Greek states. Themistocles knew full well there was little chance of survival for him at this stage, as Sparta would not let the matter go. Further, for how enlightened Ancient Greece was as a whole, there were still errors in judgment, much as in the case of the trial and death of Socrates. Themistocles was not the first hero of Greece, nor was he the last, to fall simply for contributing to, and putting his nation above all. As Plutarch himself, among others, said, the charges were undeniably false, and existed simply to destroy him. Aristides himself lived to see this ostracization occur, and it's said that, despite the intensity of their rivalry in earlier years, Aristides still regarded him warmly.

Themistocles fled to the island of Corfu, and Sparta threatened the island's king with war, were he to not immediately turn Themistocles over, even going as far as to say all of Greece would destroy him, somewhat proving that the odds of a fair trial for Themistocles were extremely unlikely. The king however, believing Themistocles to be a good man, gave him the money he needed, and Themistocles was set to leave the Greek world for good, in disguise, and embarking on a dramatic escape.

At this stage, a bounty was placed upon Themistocles' head, and he was no longer safe, even in Asia minor, particularly as Athens were laying siege to parts of the region, and there were hunters who wished to collect the illustrious bounty. For this reason, Themistocles stayed with his friends Nicogenes, the wealthiest man in Aeolia, though naturally remained in a state of dread about his affairs.

In Plutarch's telling, Nicogenes' servant and the minder of his children became enraptured after a ritual offering. His voice lifted up, and he proclaimed to Themistocles out of nowhere:

Life of Themistocles, Plutarch2

Night shall speak, and night instruct thee, night shall give thee victory.

In the night that followed, Themistocles had a dream, where a serpent coiled around his body all the way up to his neck, before transforming suddenly into an eagle and touching his face. It then wrapped him in its wings and carried him off on high, where it then transformed one final time into a golden herald's wand, setting him down, where he felt a sense of freedom from the helplessness and terror he had been feeling.

Soon after, Nicogenes sent him on his way. As it so happened, Nicogenes was familiar with the new Persian king, Artaxerxes, son of Xerxes, the latter having been slain by his own commander after the war.

PERSIAN GOVERNOR

Given the great injury Themistocles had paid the Persians during the war, Themistocles did not expect a warm welcome. In his first contact, he even admitted as such, introducing himself as he who "did your house more harm than any of the Hellene." He also spoke of the visions he received, and the bidding from the Oracle, believing Zeus had guarded him in his journey, which had been a perilous one.

Against the expectations, Artaxerxes gave Themistocles a warm welcome after all, referring to him as the subtle serpent of the Hellenes. In an even rarer showing, Artaxerxes bid that Themistocles speak his mind as he wished, jested that he owed him 200 talents for delivering himself into his custody, as if he were to claim the bounty, before offering Themistocles a place in his court and kingdom, seemingly out of sheer admiration for the man.

Under Artaxerxes, Themistocles became the governor of Magnesia, a city in modern day Turkey, where he applied much of the same political and economic wisdom he showed in Athens years earlier, and was regarded as a fair and just leader. His family soon joined him, as Athens seized what remained of his properties and wealth at home. Themistocles was not even the only famous Greek exile living in Persia at the time. The noteworthy Alcibiades, regarded as one of Greece's most prominent tacticians, not to mention a student of Socrates, also lived there for a time.

Artaxerxes, though warmer to individual Greeks than Xerxes before him, was still something of an adversary to Greece (though it should be noted he did engage with peace on the occasion). However, during his reign as king, the Hellenic issue was something of a minor concern, as he had greater issues in Asia to maintain a hold over.

It wasn't until a revolt in Egypt transpired with Athenian aid, did Artaxerxes finally call upon Themistocles to make good on his newfound loyalty and assist him in dealing with the Greeks, who were lead in the region by none other than Cimon, who had grown into a fearsome naval commander himself.

Rather than go up against his birthplace, Plutarch gives this account of Themistocles' last moments:

Life of Themistocles, Plutarch 2

... yet most of all out of regard for the reputation of his own achievements and the trophies of those early days; having decided that his best course was to put a fitting end to his life, he made a sacrifice to the gods, then called his friends together, gave them a farewell clasp of his hand, and, as the current story goes, drank bull's blood, or as some say, took a quick poison, and so died in Magnesia, in the sixty-fifth year of his life...They say that the King, on learning the cause and the manner of his death, admired the man yet more, and continued to treat his friends and kindred with kindness.

After his death, it was said that Themistocles' bones were transported back to Attica for ritual burial. The great leader Pericles himself, took a large part in the rehabilitation of Themistocles' image at home in Athens. Later, the historian Diodorus, who covered military legends like Hannibal and Alexander the Great himself, said:

Biblioteca Historia, Diodorus Siculus3

But if any man, putting envy aside, will estimate closely not only the man's natural gifts but also his achievements, he will find that on both counts Themistocles holds first place among all of whom we have record. Therefore, one may well be amazed that the Athenians were willing to rid themselves of a man of such genius.

Though not as well known as Leonidas, Themistocles is and should be remembered as a savior of Greece and of the western world at large, perhaps the greatest naval admiral in history, and as a man who, in his prime, had the Gods by his side.

Themistocles

He who commands the sea has command of everything.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Histories, Herodotus

2Life of Themistocles, Life of Aristides (The Parallel Lives), Plutarch

3Bibliotheca historica , Diodorus Siculus

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe