Augustus

Emperor of Rome

Augustus was the greatest emperor of Rome and its savior. He was the one who turned Rome into the fabled kingdom of marble, introduced endless stability and saved the realm from endless outbreaks of civil war.

His rule, known as the Pax Romana, ushered in stability, prosperity, administrative reforms, and extensive cultural achievements, transforming Rome politically and architecturally. Though maintaining republican appearances, Augustus wielded absolute authority, significantly reshaping Roman government, society, and identity, leaving an enduring legacy as one of history’s most effective and influential leaders.

THE YOUNG EMPEROR

The born in Velitrae under the name of Gaius Octavius. The alternate legend states that he was born in Ox’s Head, which was an allegory strengthening his ties to Zeus-Jupiter. His father, also named Gaius Octavius, hailed from a prosperous equestrian family that had risen to moderate prominence in Roman public life and accomplished many great military feats.

Maternally, he could claim more distinction. His mother, Atia, was the daughter of Julia, the sister of Gaius Julius Caesar. Through this maternal line, Octavius was distantly related to Caesar, a connection that would prove decisive in shaping his destiny. The elder Gaius Octavius earned respect as a capable administrator, serving as governor of Macedonia, but he died unexpectedly, leaving the young Octavius fatherless at around five years old. Regardless of how prestigious being born of such a mother was, since fatherhood was a huge currency in Rome, fatherlessness in Roman politics put one into a very precarious position.

His mother was obliged to marry a governor of Syria named Phillppus. In his early childhood, Augustus was reared primarily by his mother, Atia, and his grandmother, Julia (the sister of Caesar). This environment instilled in him a sense of familial duty, discipline, and ambition, and it kept him in the close orbit of the Julian family’s affairs. From a young age, he was exposed to the political climate of Rome one dominated by the rivalry of powerful generals, the fleeting influence of the First Triumvirate (Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus), and the undercurrents that led to civil war. Although the Octavii had not yet attained the aristocratic pedigree of Rome’s oldest families, their wealth, Caesar’s growing power. In many ways, he had to become his own father.

The situation was dangerous. Rome had degenerated from a republic of elected officials into a dictatorship under Sulla fifteen years before his birth. Caesar’s ally and eventual rival Pompey had restored the Republic, but Caesar himself had regained full power over the government in a controversial manner. Augustus was surrounded by enemies even as a child, aware that the grandnephew was a threat.

Julia and Atia’s unwavering guidance placed Augustus in an advantageous position. The former knew from observation that the boy was the best successor for her brother, who had no official heirs. Much of his life was marked by dealing not just with power player men, but the influence of powerful women.

EDUCATION AND ENTRY INTO PUBLIC LIFE

Augustus received an education befitting a Roman from a well-connected equestrian house, studying rhetoric, literature, and the basics of Roman law. His formal training likely took place under esteemed tutors who introduced him to Greek language and philosophy considered essential for any aspiring Roman statesman.

Due to his blood tie to Julius Caesar, Augustus occasionally appeared at social and familial gatherings where Caesar was present and enhanced his profile. He inaugurated and organized the Greek Games of the Temple of Venus Genetrix in a manner that impressed his uncle. By this point, Caesar had earned monumental prestige in conquering Gaul and was emerging as the dominant figure in Roman politics.

This proximity to Caesar proved formative. Augustus’ mother, Atia, saw to it that he was carefully presented to his great-uncle on other occasions, who took an increasing interest in the boy’s development. Even so, Augustus led a relatively private youth in comparison to other politically ambitious Roman teenagers, who often served in public capacities (such as the vigintivirate offices).

Nonetheless, his natural intelligence combined with a composed, calm and some would say calculating demeanor left an impression on those who met him, including Caesar himself. There was something extraordinary about the boy.

From an early age, Suetonius commends Augustus for having a strong circle of friends who rarely if ever disgraced themselves and never went against him. It seems as if the young man had the magic touch in choosing the right people to surround himself with, something that aided his quest for power greatly.

HISPANIA AND INITIAL HONORS

A notable early milestone occurred around the period Augustus when was barely in his late teens. He followed Caesar on campaign to Hispania (modern-day Spain) to fight the sons of Pompey. Though the young Octavius was too junior for a command role, Caesar allowed him to observe military proceedings, a practical schooling in the realities of war and leadership.

During this time, Octavius displayed physical courage and loyalty, reportedly surviving a dangerous crossing and breaching enemy movements to reach Caesar. Traditional sources suggest that Caesar’s regard for his grandnephew deepened because of the youth’s steadfast commitment in these difficult conditions: at this point, he became part of the inner retinue of his uncle.

Perhaps the clearest example of something Augustus learned from Casar is the incident at the Lupercalia festival. Mark Antony approached Caesar in the Forum and offered him a royal diadem (a

white fillet symbolizing kingship) in front of the crowd. According to Cassius Dio’s account, Caesar, who was seated on the rostra in his golden chair, refused the diadem and exclaimed,

“Jupiter alone is king of the Romans,”

then ordered the diadem to be dedicated to Jupiter Capitolinus.

After returning to Rome, Caesar conferred upon Augustus a few early recognition. It was nothing overtly grand, but sufficient to elevate Augustus in the eyes of the Roman elite. By this point, Caesar was dictator for ten years (later extended to “perpetuity”), reorganizing the Roman state while planning new campaigns, including a potential expedition to Parthia. Augustus, still too young for high office, nonetheless remained near Caesar’s circle, balancing humility with an eagerness to learn.

CAESAR’S DEATH

Caesar prepared a major eastern campaign, and Octavius was sent to Apollonia (on the Illyrian coast) to continue his studies and to be near Caesar’s main army. While there, he trained in military exercises, improved his Greek, and waited for Caesar to embark on what was seemingly promising to be a glorious conquest. In Rome, however, political tension simmered: many senators resented Caesar’s ever-expanding power and perceived monarchical aspirations.

On March 15 (the Ides of March), Caesar was assassinated by a group of senators led by Brutus and Cassius. His great uncle had fashioned many enemies and control of the Republic came with the ultimate price. Augustus, still in Apollonia, was not immediately aware of the catastrophic event that would change his life forever. At the moment of Caesar’s death, the only 18-year-old Augustus was known to be a competent, if largely untested, member of the Julian family.

In other words, he was promising, yet far from Rome’s conventional centers of power. Unbeknownst to him at that time, Caesar had made an extraordinary provision in his will, setting the stage for Augustus to become the principal heir and a major contender for dominance in Roman politics. Most importantly, he had also been adopted as Caesar’s own son.

In life, Augustus went by the name of Julius Caius and after adoption, Julius Caius Caesar, by the time of the princeps he became Emperor Augustus. Although a useful device for historians, he never used the form Octavius or Octavian personally.

This ended the early chapter of his life, a life soon to be encompassed by the unraveling of Caesar’s regime. Naturally, tumult would follow.

MARK ANTONY

In fact it was only after landing at Brundisium, showing his resolve, that Augustus learned of the death of his adopted father. The reason why was because Augustus had to deal carefully with Mark Antony, who was Caesar’s protégé and already a legendary figure in Rome. Due to his popularity, Antony had access to Caesar’s will and essentially acted as the legal notary.

The relationship between the two men quickly soured.

Augustus set out building his power base, massing funds from Caesar’s will. He built a loyal force of thousands of men who had grown tired of some of the corrupt aspects of the interregnum. The soldiers soon recognized the son and grand-nephew of the great republican was not at all unskilled in martial aspects himself.

He soon gained the patronage of the much of the Senate, rendering him an enemy of Antony. Cicero was instrumental in making the young man a senator and bestowing the ‘commanding power’ of the state upon him. Showing some of his military nous, he defeated him at military engagements in Mutina and Forum Gallorum.

THE SECOND TRIUMVIRATE

Augustus decided to collaborate with Antony and another powerful military figure named Lepidus, passing a motion in the Senate to officially recognize the three men as rulers, the so-called Triumvirate. Supposing that the real ambition of Antony was to conquer Persia, he allowed his suspicions to fall to the wayside for a while. His main concern was to defeat the pirate navies of Sextus Pompey, the son of Pompey who had gone rogue.

Over the years, Antony went back and forth to Egypt to see Cleopatra, the Pharaoh of Egypt. He was also involved in an affair with Glaphyra, the queen of Cappadocia. In anger at Augustus, Antony’s actual wife Fulvia (the most powerful woman in Rome) and his brother Lucius instigated yet another civil war, which Augustus had to put down carefully.

The two came to a sort of conciliation after Fulvia’s death from an illness. The great man of Rome progressively ignored Octavia, the sister of Augustus who had been given to him in marriage to cement peace. She raised an army in protest of this and even went as far as Athens. Augustus created laws to make his sister and wife Julia sacrosanct and gave both of them all rights that Roman men had.

Augustus knew his grand-uncle Julius Caesar had a child with the ruling Pharaoh of Egypt, the famous Cleopatra, who was named Caesarion. He also witnessed that Antony quickly became the boy’s adoptive father and had numerous children with Cleopatra named to establish their connection to Alexander the Great, provoking some concern from him.

WAR OF ACTIUM

Mark Antony was now becoming increasingly aggressive and had taken on a status of being quasi-Pharaonic. Egypt was still the wealthiest country in the Mediterranean. Cleopatra, a powerful, brutal and astute woman, had spent much of her reign renovating the country’s fortunes. Following this, she also had ambitions to expand the Empire of her ancestors. To this extent, Antony gave large amounts of Roman territory to Egypt, which outraged the Roman people.

The War of Actium began. The soon-to-be emperor isolated the armies of Antonius in Greece through a variety of tactics, including destroying supply lines, forcing starvation and luring away Antonius’ naval commanders. Augustus moved against the couple in various naval battles, culminating in the Battle of Actium, where Rome’s smaller fleet of ships overpowered Anthony and Cleopatra’s forces. The friendship of Augustus to Marcius Agrippa and Lucius Arruntius greatly aided him in this battle.

It is known that the ruler of Rome exhibited exceptional clemency to Antonius’ allies, even allowing a major commander, Sosius, to become wealthy and build a temple to Apollo in Rome. Augustus soon landed in Egypt and annexed the country to Rome altogether, ousting Cleopatra, his great rival.

THE RECONSTRUCTION OF ROME

Augustus did have some respect for republican ideals. He did not intend to turn Rome into a dictatorship of one but felt that squabbling among the Senate had essentially destroyed the Republic and that it was dangerous to return to partisan politics. Compared to many emperors, even individuals shouting at him were almost never punished. Still, the sources indicate his exasperation:

As he was speaking in the senate someone said to him: "I did not understand," and another: "I would contradict you if I had an opportunity." Several times when he was rushing from the House in anger at the excessive bickering of the disputants, some shouted after him: "Senators ought to have the right of speaking their mind on public affairs."

At the selection of senators when each member chose another, Antistius Labeo named Marcus Lepidus, an old enemy of the emperor's who was at the time in banishment; and when Augustus asked him whether there were not others more deserving of the honour, Labeo replied that every man had his own opinion. Yet for all that no one suffered for his freedom of speech or insolence.1

It was his philosophical training that led him to believe that there was a necessary to create a universal empire where the head of the state commanded a modicum of universal respect, rather than an unstable succession of officials at war with each other.

As he held that Roman life had starkly degenerated to the point of political corruption, Emperor Augustus attempted to reform Rome under moral principles. He took influence from many of the classical philosophers in attempting to achieve this. Public displays of extreme lewdness were banned. Aristocratic and religiously-based privileges were reinforced, but Augustus also gave extreme amounts of money to the poor for their relief, possibly the most of any emperor.

In line with the Republic, the emperor demanded that the arts cultivate virtue and not just an endless succession of excesses. Despite this, he attempted to permit freedom of speech as much as possible and to simply fight his own corner, even when personally attacked:

When he was assailed with scurrilous or spiteful jests by certain men, he made reply in a public proclamation; yet he vetoed a law to check freedom of speech in wills.1

It is also notable that Augustus had a habit of using his own purse to renovate the Empire: a huge maintenance work of all roads and ways in Italy was paid for by his own money, rather than the Senate.

The emperor was a great follower of Greek learning and of Hellenism, yet he also had to be pragmatic and evoke the image of Rome’s ancient days. He stimulated much Greek learning in Rome and was the patron of many philosophers of the time.

LAWS OF ROME

Augustus enacted legislation focused on restoring traditional Roman family values and morality, known famously as the Julian Laws (Lex Julia) and the later Papia-Poppaean Laws. These laws targeted marriage, adultery, childbirth, and inheritance. For instance, Augustus introduced the Lex Julia de Maritandis Ordinibus in 18 BC, encouraging marriage and childbirth by offering incentives such as tax benefits, while penalizing unmarried men and women. Similarly, the Lex Julia de Adulteriis Coercendis criminalized adultery, enforcing strict penalties for violators, which reflected Augustus’s determination to restore traditional Roman social virtues.

He also brought back major sumptuary laws, marking out the aristocracy from the peasantry and forbidding illicit contact. Many of these measures were designed to instil respect of Rome’s leadership.

ECONOMIC POLICY

Prior to his reign, Rome's economy suffered from frequent financial instability and inconsistent coinage, undermining commerce and trade. Augustus standardized the coinage, introducing stable gold (aureus) and silver (denarius) coins with fixed weights and purity, facilitating easier trade and stabilizing prices.

The emperor initiated massive infrastructure projects, including roads, aqueducts, and ports, improving transportation, trade efficiency, and stimulating economic growth. He rebuilt and beautified Rome, attracting commerce, increasing employment, and boosting local economies. Secured trade routes across the Mediterranean and beyond through military and diplomatic stability, expanding commercial markets and prosperity.

Secondly, Augustus revolutionized the taxation system, establishing fairness and predictability in revenue collection. He instituted a regular census to accurately assess taxation liabilities across the empire, replacing the often arbitrary and exploitative practices of the Republican era. This systematic taxation not only increased imperial revenues but also built public trust and reduced resentment among the populace. Additionally, he created the aerarium militare, or military treasury, financed through inheritance taxes and other targeted levies. This provided a dedicated and stable revenue stream to support veterans and active military personnel, thereby ensuring loyalty and internal security.

Agricultural reforms were another critical aspect of Augustus’s economic strategy. Recognizing agriculture as the backbone of the Roman economy, the emperor encouraged the settlement of veterans in rural colonies, providing them land and incentives to engage in farming. This policy rejuvenated rural regions devastated by previous civil wars, increased agricultural productivity, and stabilized food supplies particularly grain to Rome and other urban centers, thus controlling prices and preventing food shortages and civil unrest.

REFORMS OF RELIGION

Augustus had at least 82 elaborate Temples built for the Gods and many more were restored or renovated from states of disrepair, including the oldest Temples inaugurated by Rome’s ancient kings. His general commitment to the Gods was a very serious one.

Both he and Julia underwent the Eleusinian Mysteries, indicating that Augustus’ pretense towards religion was not designed for self-affirmation. Major aspects of Augustus’ religious policies can be found on the Jupiter page.

To illustrate the seriousness of religion, he upgraded the office of the Pontifex Maximus, embodying it highly in a symbolic role. He also built an elaborate temple to Jupiter Tonans in thanks after lightning very narrowly missed him.

After the defeat of Cleopatra, Augustus was also keen to display himself to the Egyptians as a worthy Pharaoh. Contrary to traditional accounts that the Romans simply stripped the country of its resources, significant amounts of Egyptian temples were built and consecrated during his rule; Augustus was keen to illustrate an above average interest in Egypt.

OCCULT SYMBOLISM

Due to Augustus, we have the month of August, the month of many of his military successes. This replaced the traditional month, Sextilis.

Augustus often used the imagery of Capricorn, his own Chart Ruler sign, to illustrate his primacy as an Emperor. This also illustrated his relationship with Zeus, as this is the sign of all rulership, the Truth of the universe and highly representative of capstone of consciousness. A number of aspects of his imperial cult relay an intimate connection to the divine, a matter that was also instigated by his rivals who used Dionysian imagery to justify their rule.

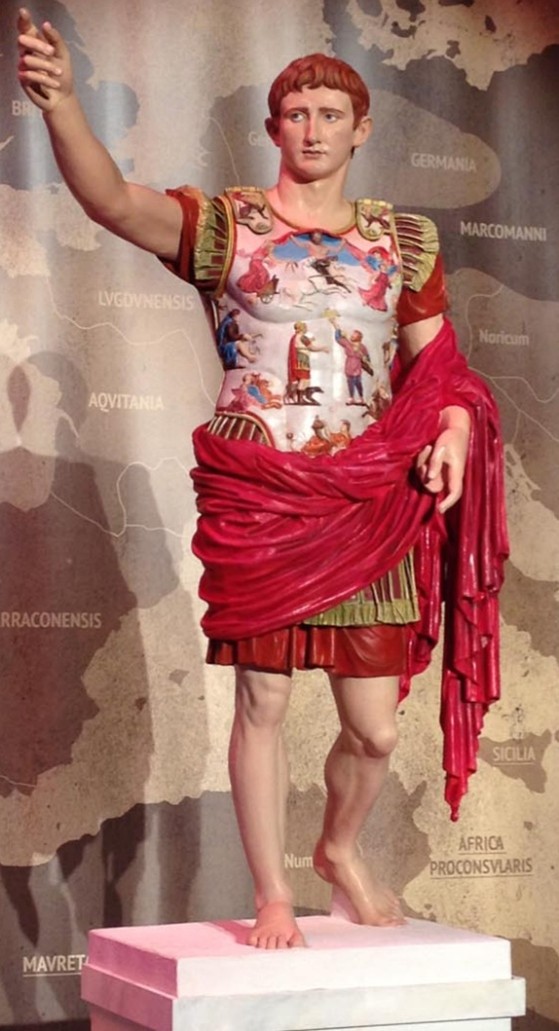

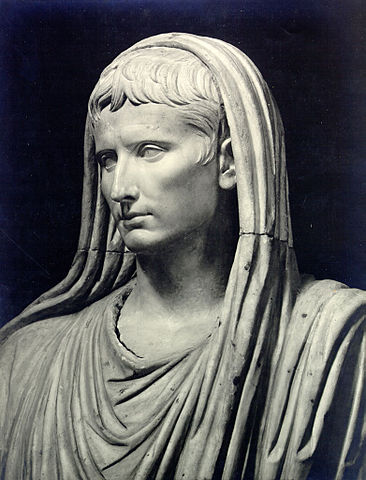

He also directly used much of the imagery of Zeus-Jupiter to convey clearly to the people of Rome that his reign was meant to represent true and philosophical kingship at the head of a commonwealth. Many of his statues show him in the head veil of the Pontifex, showing his piety as a ruler.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Life of Augustus, Suetonius

Lives of the Roman Emperors, Suetonius

The Roman Revolution, Ronald Syme

Augustus: Image and Substance, Barbara Levyck

Augustus, Pat Southern

CREDIT:

[TG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe