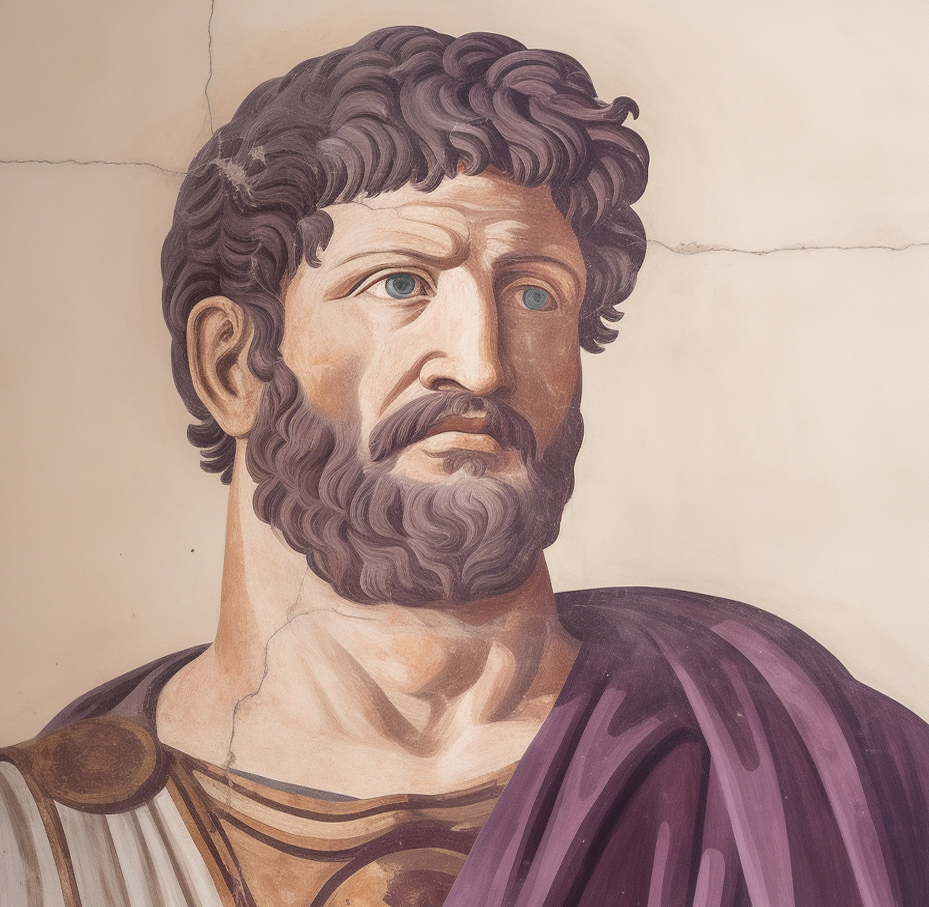

Hadrian

Emperor of Rome

Emperor Hadrian (reigned 117–138 CE) was one of the most capable and well-rounded Roman emperors, known for his intellectual depth, administrative reform, military strategy, and architectural achievements. Succeeding Trajan, he shifted Rome’s focus from expansion to consolidation and internal stability, famously abandoning Trajan’s eastern conquests and drawing back to more defensible frontiers. He traveled extensively across the empire, personally inspecting provinces, fortifications, and civic institutions. His military strategy was defensive but effective, exemplified by projects like Hadrian’s Wall in Britain, built to mark and secure the empire’s northern boundary.

Hadrian was also a patron of the arts, philosophy, and Hellenic culture, embodying the ideal of the philosopher-king. He sponsored massive building projects such as the Pantheon in Rome (as we see it today), and his Villa at Tivoli was a showcase of Greco-Roman art and engineering. Intellectually curious and highly educated, he cultivated relationships with Greek thinkers and poets, embracing a cosmopolitan identity. Though his reign was largely peaceful and prosperous, it ended with the Bar Kosiba Revolt in Judea, a brutal war sparked by Jewish intolerance. Nonetheless, Hadrian left a legacy of strong centralized governance, architectural splendor, and a model of imperial leadership that influenced Roman and European ideals for centuries.

EARLY YEARS

Hadrian was born in the province of Hispania (modern day Iberia) to an Italian family of upper-class origin. His father, Hadrian Afer, had been a Roman senator and his mother Domitia Paulina also came from a distinguished family that served the Senate, thus it was not unexpected that the young boy would come to play a large role in public life. Soon, his ambitious cousin Trajan would become Roman emperor.

During his youth, he showed a particular fondness for Greek learning, habits and philosophy, which earned him the nickname of Graeculus (“Greekling”). He was also highly unusual in training himself to large extents in music (such as the kithara) and dance, which many aristocratic Romans considered highly disreputable endeavors.

Hadrian was known as a highly skilled sculptor who was compared to Lysippus in talent, again blurring the lines of what was appropriate for an aristocrat. It could be said that his attempt to master as many skills as possible came out of a veritable love of life. It is known that he aligned more closely with the Epicureans than other schools of philosophy and that reflected his larger-than-life persona.

RISE TO POWER

Hadrian’s parents had died early. Consequently, he became a ward of emperor Trajan and the empress Pompeia Plotina, who herself was a devotee of philosophy. Plotina became one of the most important mentors of Hadrian. No exaggeration could be put forth in calling her the patroness of Hadrian: she encouraged his philosophical education, helped his entry into politics and even taught him how to rule. She could see that he was the best individual to designate as an heir.

Despite the perception in modern times of Hadrian as being a cultured ruler, it is a necessity to state that Hadrian was more ruthless and prone to eliminating his enemies than Marcus Aureliusor Julian. A conspiracy to kill Hadrian involving four senators, including Nigrinius, his designated successor, ended in the emperor issuing orders to hunt them down and put them all to death.

Hadrian was aware that despite his military successes in Dacia, he did not have the military cachet of Trajan, one of the most competent commanders of Rome. The extremely violent Kitos War had also left an impression on him that security was a necessity. He almost certainly issued this order, which, dangerous as the conspirators were, outraged the Senate for the rest of his reign and continued to have ramifications as the institution defied him again and again.

KITOS WAR

The young would-be emperor was learned and not inclined towards particular hatred. Hadrian's approach to the Jewish populations involved a mix of leniency and caution. He rolled back some of Trajan’s policies and restored order to the Eastern provinces without immediately pursuing harsh retribution against Jewish communities.

He seems to have allowed the communities in the Eastern Mediterranean to recover, likely recognizing the economic and demographic cost of prolonged unrest. He also refrained from antagonizing the Jews initially, possibly in hopes of long-term pacification, as his broader policy during his early reign leaned toward peace, consolidation, and infrastructure rather than conquest.

THE WORLD CITIZEN AS EMPEROR

Believing totally in the concept of the philosopher king, Hadrian wasted no time in scouting out every province of the empire, identifying matters for improvement. Mismanagement by a succession of emperors after Augustus had brought Rome into a number of problems. He sought to unify the provinces of Rome under a Hellenistic set of cultural and political practices, to bring them up into a commonwealth of equal prestige and power, seizing on the peace Nerva and Trajan had brought.

Although the sources indicate that he had a reputation for luxury and enjoyment, Hadrian spurned many of the traditional practices involved in travel and projecting power to citizens. He was known to even walk barefoot in front of his retinue and bodyguards, even traversing steep mountain paths to investigate local matters in detail. Above all, this demonstrates his determination to be practical.

Traditionally, it was seen as irresponsible for the emperor to reside outside of Rome and Hadrian’s mentality of putting provinces on par with Italia soon inspired a certain degree of criticism from Roman traditionalists, who also felt that his actions were more becoming of a citizen than a ruler.

HELLENIC EMPEROR AND FRIEND OF ATHENS

His massive commitment to Athens meant that he was appointed its’ archon for a year. Hadrian’s time in Athens was spent learning about Greek philosophy and the nature of Greek statehood in as much detail as he could muster. Fluency in Greek also became a major achievement for him.

In Rome, Hadrian established a cult for the city itself and several years later, a temple, the largest in the city, was dedicated by the emperor to ‘Romae Aeternae.’ Hallowing back to Julius Caesar, Hadrian adopted Venus Genetrix as patroness of the imperial family.

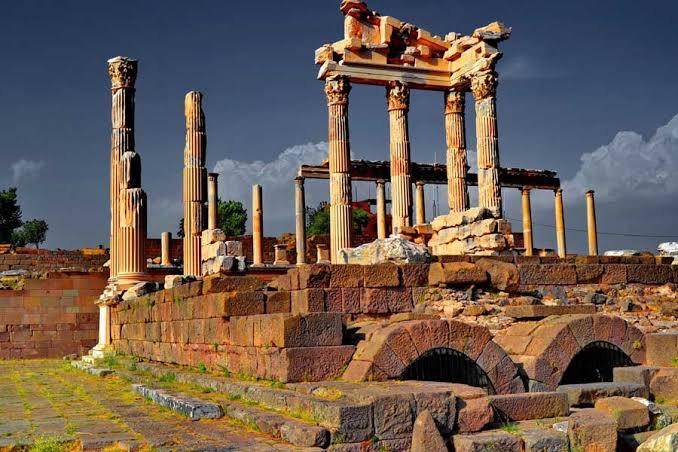

Back in his beloved Greece, Hadrian was initiated into the mysteries of Cabiri at Samothrace in the Aegean. The following year, in Athens, Hadrian was initiated into the rites of Demeter at Eleusis and the rites of Dionysus. Hadrian ordered the restoration of the Temple of Zeus Olympios which had lain in ruin for three centuries. He also oversaw the restoration of Phidias statue of Zeus at Olympia and the Sanctuary of Poseidon.

He convinced the irate and hostile representatives of Sparta and Athens to become Senators in Rome, indicating the first time that leaders of the Greek states had any particular say in Roman politics. This gesture did not make him popular among the Senate, but it showed his grand ambition to incorporate the majesty of Greece into the Roman Empire.

Hadrian erected elaborate and beautiful statues to both Leonidas and Epaminondas. The Asclepions across the Roman Empire were also renovated to a grandiose degree under his watch. Hadrian also made Sagalassos the cult center of Roman religion, one of the most powerful sites on an occult level that he was able to find.

REFORMS OF ROMAN LAW AND RELIGION

Yet Hadrian was not necessarily only a Hellenist as many believe. He sought to revive the core religious principles of the Roman state which in his mind had become increasingly obscured in Roman life. In this, he did not just draw on Solon and Athenian sources, but directly on the example of Numa Pompilius, the semi-legendary King of Rome, which all contemporary sources corroborate as his direct inspiration for reforming Roman religion.

The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, first instated by Tarquin, was given massive renovations in scope. To this, he also engaged in large renovations of the Temples of Juno and Minerva, a divine triad from ancient Rome that was tied to the Hadrianic Order.

When emperor, he constructed the Athenaeum in Rome, an institution built for the purpose of scientific and philosophical study, but in reality one of the first major universities of the world. Grammar, law, philosophy, poetry, oratory and numerous other subjects were taught at this seat of learning. He brought the Eleusinian Mysteries to the capital city from Athens, knowing that many talented people wanted to adhere in the rites. Rome from this point became known for circles of philosophers.

In addition to the civic matters outlined above, Hadrian also reformed many of the laws of Rome and created the first empire-wide codification through the jurist Salvius Julianus. Even senatorial and Christian sources from late Rome and as far as the conquest of Constantinople that are highly antagonistic to him put all credit to Hadrian first and Marcus Aurelius second for the civic structure of the Roman state in their eras.

He favored an aristocratic policy in law, attempting to create a parallel body that could bypass the Senate which despised him. Taking inspiration from Augustus’ reforms, he reaffirmed sumptuary laws where people were obliged to dress according to their class.

Hadrian banned many practices in the Roman Empire that were considered culturally aberrant and evil. Knowing of the allegations of Apion towards Jews sacrificing a Greek every year, his laws proscribed human sacrifice with extreme penalties. He reinforced the ban on castration from Domitian’s time; even those who castrated slaves were put to death immediately, with castration being equivocated with murder.

As Jerusalem had been razed totally by Titus, he decided to create a new city in the province of Judaea called Aelia Capitolina to stabilize the situation. It was a grandiose project: it had baths, temples, libraries, utilities and many other elements. Jews, however, were forbidden entry other than on Tisha B’av.

Hadrian hoped this settlement would eventually rival Alexandria without any of the mistakes plaguing that city. The Hebrews were outraged, particularly at the presence of the Temple of Capitoline Jupiter housed there. In particular, they openly reviled the Gods and demanded the removal of the Gods from Judaea.

BAR KOSIBA JEWISH WAR

A massive revolt again broke out in Judaea.

According to Hadrian, the major pretext of the war was simply the empire-wide ban on circumcision, nothing else. Yet it was also clear that the Hebrews had been preparing to enact revenge and were enraged also at the census of Rome:

A high-level rabbinical initiate, Simon bar Kosiba (known as ‘bar Kokhba’, meaning ‘son of the star’, in history), had been recently proclaimed the messiah of the Jews. In this, he was supported by one of the high priests of the Jews and one of the major Kabbalistic scholars, Rabbi Akiva, who directly named him the messiah. This individual was so famous in their literature that he is mentioned by name in two variations of the Talmud.

Inflaming matters was a prophecy by the Jews that their temple would be rebuilt, seventy years after the destruction of the first by Titus. The situation spun out of control quickly. Intending to seriously destabilize the imperial project of the hated Romans and Greeks, bar Kosiba’s armies of 100,000 Jewish insurgents initiated a mass murder of settlers through guerilla warfare in the troublesome province and even killed any Jews suspected of Hellenizing.

Hadrian sent a massive military force of several legions to the province, progressively crushing the revolt in its entirety. As with the Kitos War, the fighting was particularly vicious, yet this time it took on an even more extreme character. A huge amount of the Hebrews died or were sold into slavery.

Immediately, Hadrian sought to Hellenize the province rigorously. Aelia Capitolina, despite the allegations by various liars across history such as Eusebius of Caesarea, was created prior to the war and suffered immensely from the rebellion. Still, the prophecy of the Jews came true, but not in a manner they appreciated.

Hadrian executed the entire rabbinate, including Akiva. The legion of Cyrene which was primarily made up of Greeks related to those destroyed by Jews during the Kitos War exterminated the remnants. The emperor quickly erected a gigantic temple to Zeus Hypsistos (Highest Zeus) on Mount Gerizim with the seized bronze doors from the Temple, a final attempt to impress onto the Jews the necessity of Godliness. After the revolt, the penalty for a Hebrew upon entering Aelia Capitolina was death.

This was a massive setback for the Hebrews; their contacts with the Roman leadership that had been stimulated since the days of the Punic Wars had been smashed. Furthermore, the reputation of the Jews in Alexandria infamously now lay ruined. Romans, Greeks and Egyptians ceased to trust them altogether. After this humiliation, there had to be a ‘different way’ to destroy Rome.

The province was renamed to Syria Palestina, a throwback to the name it had during the Seleucid Empire prior to the Hasmonean Jews seizing the land. Hadrian also prioritized the priesthood of Emesa and the Syrian Arabs in guardianship of the province who would contribute to the empire’s history heavily in the next two hundred years.

ANTINOUS

Hadrian cultivated a close association with the beautiful youth Antinous, something that continues to be a source of controversy. Underlying this, beyond anything else, was the fact that Antinous, of rather humble background, was one of the most spiritually advanced individuals he and Plotina could find in the entire empire at a precocious age.

Understandably, other than those who had the spiritual sight to see what Antinous actually was, the senate was also not happy with this relationship, which they considered inappropriate and oriental. Much venom has been directed towards Antinous over the ages, particularly as Christians sought to attack his cult as an effeminate royal posturing and use it cynically to refer to the superiority of the myth of ‘Jesus’, who never even existed.

In comparison to many of the inappropriate relationships of rulers to humble subjects across history, it is known that Antinous never personally used his connections to Hadrian for any personal benefit whatsoever.

END OF LIFE

By the early 130s CE, he was afflicted by a chronic and painful illness, likely heart or kidney failure, which left him bloated, weak, and often unable to walk. Despite his illness, he continued to rule actively, but his temperament reportedly became erratic and suspicious. His inability to produce a biological heir created political uncertainty, leading to a series of adoptions, first Lucius Aelius (who died young), and later Antoninus Pius, whom Hadrian adopted with the stipulation that Antoninus would in turn adopt Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, ensuring dynastic continuity.

Hadrian spent his last years at his Villa in Baiae and later at his massive Villa at Tibur (Tivoli), where he withdrew from public life and struggled with worsening health. He died in 138 CE, at the age of 62, in Baiae. His succession plans were smoothly carried out, and Antoninus Pius became emperor. Although the Senate initially resisted deifying Hadrian due to lingering resentment, Antoninus pushed through his divinization, earning him the title “Divus Hadrianus.” Despite the darker aspects of his final years, Hadrian was ultimately remembered as a thoughtful, cultured, and effective ruler, whose administrative and cultural legacy outlived his personal struggles.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Life of Hadrian, Historia Augusta

Roman History, Cassius Dio

De Caesaribus, Aurelius Victor

Hadrian: The Restless Emperor, Anthony R. Birley

Hadrian and the Cities of the Roman Empire, Mary T. Boatwright

CREDIT:

[TG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe