Pericles

Great Ruler of Athens

Pericles was the most influential statesman, military leader, and orator of what is known as the Golden Age of Athens. Under Pericles' leadership, Athens reached its peak in art, literature, politics, and philosophy; it became the most powerful and culturally influential city-state in the Greek world. The fact that his era is called the “Age of Pericles” is the greatest indication of the profound and lasting impact of his leadership.

YOUTH OF THE POLITICIAN

Pericles was born into one of the noble families of Athens, of the paternal tribe known as Acamantis and the demos of Cholargus. His father, Xanthippos, was a commander who won a victory over the Persians at the Battle of Mykale, and his mother, Agariste, was from the famous Alcmaeonid family, an extremely powerful dynasty in Athenian politics. Agariste was the great-granddaughter of Kleisthenes of Sicyon, a former tyrant of a city in Sicily, and also the niece of the more famous Kleisthenes who expelled the tyrannical Pisistratid dynasty, established the Athenian Boule, and organized the development of Athenian democracy.

Complex developments involving his other ancestors and future relatives, such as Alcibiades and the circle of tyrants with whom Alcibiades would associate, made hailing from this complicated family network both a boon and a hindrance. Belonging to such a noble lineage gave Pericles a significant advantage in his political career, yet the memory of his more tyrannical ancestors and the scandals of his younger relatives also clouded perceptions of his own motives. Plutarch also claims that this was not helped by Pericles’ eerie and striking resemblance, in both form and voice, to the tyrant Pisistratus, head of the rival Pisistratid clan, still within living memory for many of the elderly.

Although not much is known about his youth, Pericles is remembered as a quiet, thoughtful, and contemplative boy. He received a fine education, verging on the cutting edge of intellectual developments in Athens, particularly toward the philosophical schools beginning to flourish in the city. Building on these foundations, which were not enough to satisfy him, Pericles sought the counsel of famous philosophers such as Protagoras, Zeno of Elea, and Anaxagoras. Under their influence, Pericles refined his worldview and grew increasingly committed to merging philosophical tenets with political participation. He later developed close relationships with Socrates and other philosophers who are known to have communicated directly with him, though many of these figures would later harbor an ambivalent view of him as a leader.

With this education, Pericles reinforced his commitment to the democratic structure of Athens, while also developing into a logical and strategic leader with a certain confidence and charisma. In part due to the tutelage of Anaxagoras, who impressed upon him the idea of an impersonal intelligence animating the universe, Pericles became a strong advocate for allowing people to shape the character of the state and to follow the dictates of their own free will. Accordingly, he fundamentally disagreed with heavy-handed methods and violent interventions into individual lives, a method his ancestor in Sicily had deviously and disastrously employed.

It can be said that Pericles held certain spiritual viewpoints concerning the holiness of free will, which shaped his conception of politics. With time and patience, the wise exercise of these principles under his hand became a key element in the strengthening of Athenian power. Yet Pericles’ obsession with democracy and free will also led to severe problems down the line. For this reason, his name has gone down in history as that of a man who gambled with fate and the will of the masses.

EPHIALTES

Although Pericles’ entry into the Athenian political scene began at a young age, it was his reforms alongside Ephialtes, an advocate of democracy, that had the greatest impact at the beginning of his career. In 462 BC, Pericles and Ephialtes initiated important reforms aimed at limiting the power of aristocrats and increasing the influence of other social groups in politics.

One of Pericles’ primary political enemies was Cimon, a war hero of Athens, firm oligarch, and resolutely pro-Spartan in taste, though also a generous benefactor of the poor. Some historians accuse Pericles of having less-than-pristine motivations, as the popular reforms he proposed had the effect of ousting Cimon and his supporters from power. The most important of these reforms was the limitation of the powers of the Council of the Areopagus. Dominated by the nobility and entrusted with certain religious and legal functions, the Areopagus was a stronghold of oligarchic influence. This reform marked a turning point in the strengthening of Athenian democracy.

Cimon met with personal disaster when an army under his command was rebuffed by the Spartans while trying to assist with a helot revolt, an idea already extremely unpopular with the Athenian masses. At the same time, the extreme tendencies of Ephialtes in harassing oligarchs would soon alienate Pericles.

In the meantime, Pericles cultivated a public image as a learned and reserved man, even while extolling the benefits of luxury and beauty to the populace. To that end, he abolished certain privileges of the nobility and refused to partake in large-scale drunken banquets, instead offering the people promises of shared political power. The largesse he showed to the populace, combined with his image as a living example of virtue, gave him tremendous power in Athens.

After Ephialtes was assassinated [likely by one of the oligarchs], Pericles became the most powerful political figure in Athens. He further developed democratic structures and introduced arrangements that allowed common people to play a more active role in politics. His personal commitment to democracy, tempered by moderation in contrast to Ephialtes’ extremism, gave him wide appeal and led to unprecedented levels of public participation. He strengthened the powers of the Boule and passed laws encouraging citizens to participate directly in decision-making within the assembly (Ekklesia). Every male Athenian citizen who had completed the mandatory period of military service now had a voice in the Ekklesia, where matters of state were debated and decided.

One of Pericles’ most important reforms was the introduction of residual payment for public office in the Boule, an initiative he considered an improvement over the restricted system of his great-uncle. Where once only the wealthy could afford to hold public office, Pericles established a system where politicians of any origin were paid to represent the demos, thereby enabling poorer citizens to serve in public life. For better or worse, a large segment of society now had the power to shape the Athenian state, yet paradoxically, this empowered Pericles himself, who came to be known to all as the "First Citizen."

THE BLOSSOMING OF ATHENS

On the other hand, Pericles also sought to render Athenian privileges strictly for Athenians. A controversial law of his limited Athenian citizenship to those born of two Athenian parents, making someone born of only one citizen a metic (a legal foreigner with restricted rights). Although this law was overwhelmingly aimed at other Greeks, it has given Pericles a reputation in certain circles for being an ethno-centrist or a harbinger of modern nationalism and populism.

Under Pericles' leadership, Athens became not only a military and political power, but also a cultural center. Pericles undertook major projects to make Athens the intellectual and artistic capital of the Greek world, as he believed that mousike (the arts) would elevate the spiritual lot of the population, entrenching their commitment to political and military efforts. Because of this, he even pushed forward a policy allowing the poor to watch plays without paying hefty admissions.

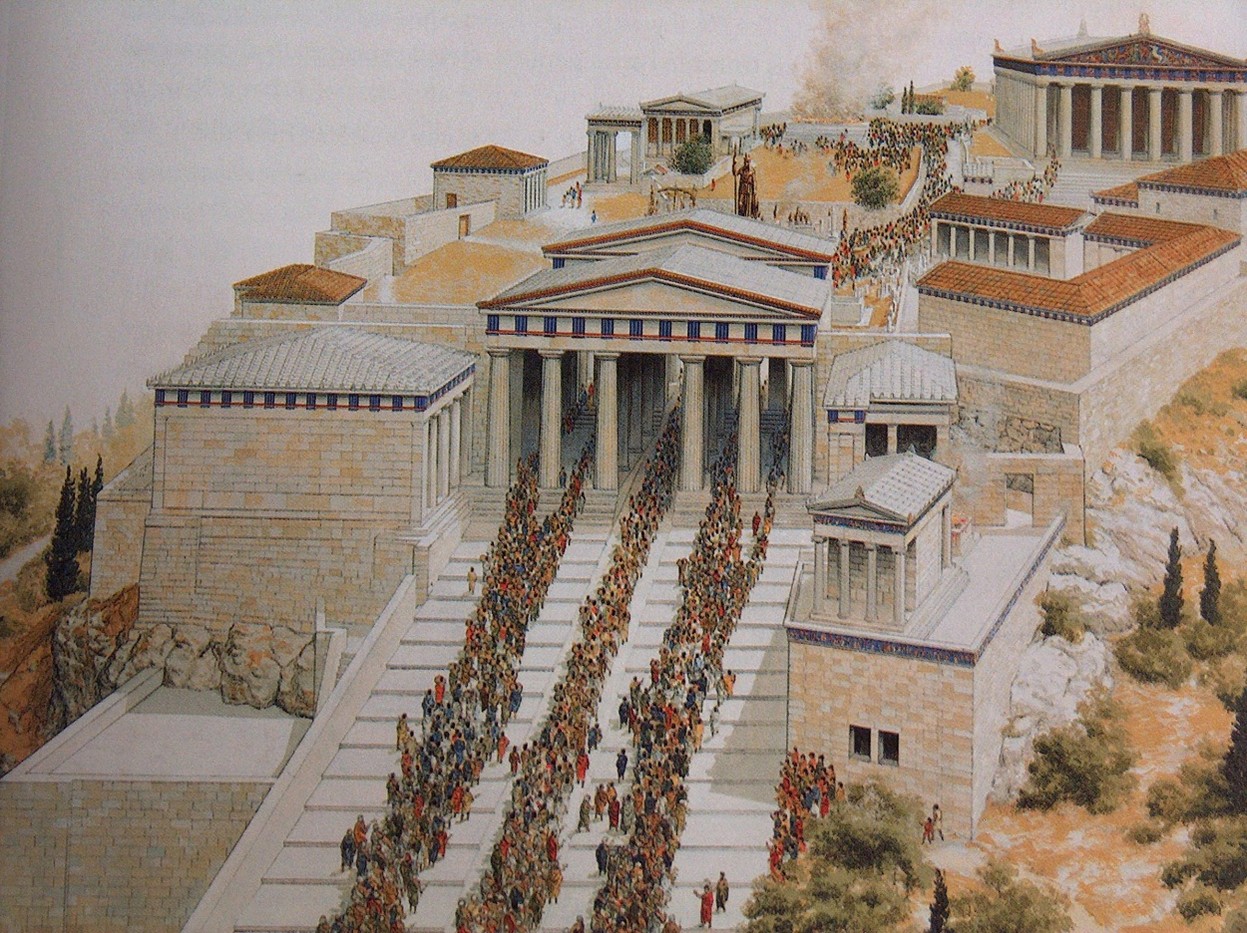

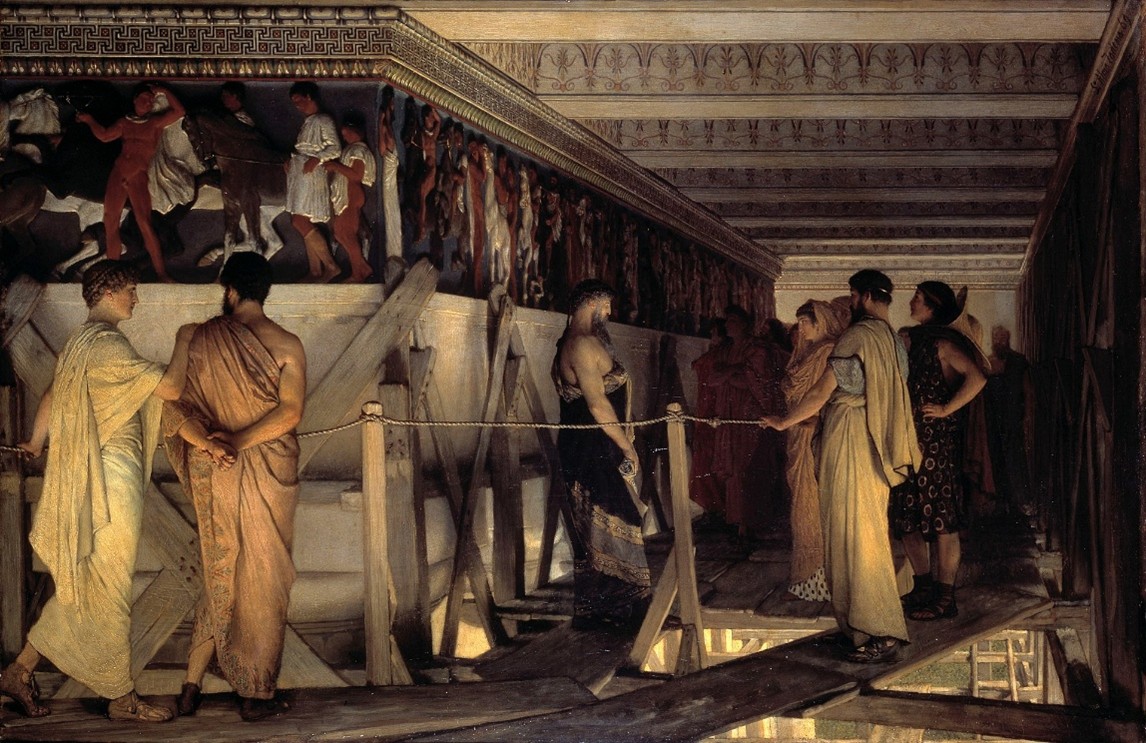

One of Pericles' greatest achievements was his massive construction projects on the Acropolis of Athens. The Parthenon is the largest and most famous of these. Built in the name of Athena Parthenos (Virgin Athena), the temple is considered one of the greatest works of architecture and art of the period, still standing to this day. The Parthenon symbolized the wealth, power, and cultural superiority of Athens, an eternal testimony to the power of the state.

Pericles was known to have associated Athena as his patron deity. Beyond merely paying homage to the city’s Goddess, he encouraged this visual association due to the theory of Nous (the cosmic mind setting things in proper order) that Anaxagoras had formulated: Athena was associated with the concept of Nous. Pericles believed that shaping Athens into a culturally distinct realm through human ingenuity and the arts gave it an advantage as a rational and orderly entity.

With all these efforts under the leadership of Pheidias, Plutarch relates that Athena was greatly pleased by the construction of these buildings. A skilled artisan who had fallen from a great height and nearly died while working on the Parthenon was seen as a bad omen for the project and greatly troubled the Athenian leader. Yet She appeared to Pericles in a dream and recommended a treatment regimen that successfully cured his dire state, upon which Pericles built a golden statue to Athena Hygieia.

by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

He was also keenly aware that conscripting the non-military elements of the city and keeping them occupied in productive matters was highly important. This was a secondary reason Pericles pursued these projects, yet it played a major role in quelling discontent between the military and civilian classes, forging a sense of civic unity that constituted the era of the so-called Pax Athenaica (Athenian peace).

These major construction projects transformed not only the appearance of Athens but also the cultural identity of the Athenians. In a sense, under Pericles, Athens became not only a military power but also a leading city in the arts, science, and philosophy. Within the blossoming of this intellectual atmosphere, sculptors like Phidias, philosophers like Socrates, and playwrights like Euripides and Sophocles came to the fore.

ORATORY

Oratory is an area where Pericles continues to maintain strong fame. Scintillant speeches, effused with verve and style and relayed by Thucydides, such as the Funeral Oration, are cornerstones of Western political theory and literature. Historians point out that the expressive power of the Athenian leader was enough to vanquish enemies and quell numerous scandals. These speeches also stand stylistically as some of the most masterful tracts of Attic Greek: Pericles was known to wield language as a weapon, inventing new words on the spot that became part of the Attic lexicon. In this sense, he is comparable to Shakespeare’s stature in English.

As a leader, his speeches were few and far between, commonly delivered during crises for ultimate dramatic effect, leading some historians to accuse him of being manipulative and demagogic. When engaging the public, he posed rational solutions to the problems of the demos and sought to channel the frenzy of crowds into practical outcomes through encouragement of bravery and passion in the citizenry. In every speech, Pericles emphasized the privilege of democracy and freedom of thought as cornerstones of Athenian greatness, for which they must fight or die.

It was from natural science, as the divine Plato says, that he “acquired his loftiness of thought and perfectness of execution, in addition to his natural gifts,”

and by applying what he

learned to the art of speaking, he far excelled all other speakers. It was thus, they say, that he got his surname; though some suppose it was from the structures with which he adorned the city, and others from his ability as a statesman and general, that he was called Olympian. It is not at all unlikely that his reputation was the result of a blend of many high qualities. But the comic poets of that day, who let fly, both in earnest and in jest, many shafts of speech against him, make it plain that he got this surname chiefly because of his diction; they spoke of him as “thundering” and “lightning” when he harangued his audience, and as “wielding a dread thunderbolt in his tongue.”1

Pericles made strategic moves to develop Athens' maritime power and expand the city-state's sphere of influence. He formed the Delian League, which began as a defensive alliance against the Persian Empire but eventually turned into a vehicle for Athenian hegemony. With money collected from the League's members, Athens expanded its naval power and established the most formidable fleet in the Mediterranean. The commercial elements of Athenian life also expanded to grandiose levels.

However, this hegemonic posture began to cause discomfort among other Greek city-states. Certain colonies and allies chafed under the exorbitant sums they were compelled to pay Athens merely for the city’s glory. Sparta was particularly alarmed by Athens’ growing power and its domination over other city-states. As a result, relations between Athens and Sparta became strained, leading to the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War toward the end of Pericles' reign.

THE END OF THE GOLDEN AGE

In his final years, the Peloponnesian War broke out between Athens and Sparta. This war would shake the Greek world for decades and mark the end of Pericles' career. When it began, Pericles led Athens’ military and strategic decisions. Knowing Athens could not win a land battle against Sparta’s hardened forces, he opted for a defensive war strategy. He envisioned the Athenians staying within their walls, while the navy dominated at sea. Rather than confront Sparta's powerful land army directly, he planned a long-term war of attrition based on naval supremacy.

Athenians were quickly ordered to stay within the city walls and resist Spartan attacks. However, since much of the population lived outside the city, crowding inside the walls created unexpected and severe problems. A great plague broke out in Athens. With the city's population trapped, the disease spread rapidly, killing a large portion and negatively affecting the war’s course.

Pericles was among the plague’s victims. His death was a great loss for Athens. During his years as leader, he had won the people’s trust as a charismatic and strategic figure. After his death, Athens struggled in the Peloponnesian War. Political instability rose, and eventually Athens was defeated by Sparta.

Following Pericles' death, Athens faced internal political conflict and leadership crises. Without his strategic acumen and unifying influence, the city underwent a series of coups and disastrous failures. This defeat marked the end of Athens’ Golden Age and the brief rise of Sparta, which was later eclipsed by Thebes and the emerging Kingdom of Macedon.

Pericles' legacy was not limited to Athens’ political and military power but also left a deep mark on cultural, artistic, and intellectual life. Many developments that defined the Golden Age of Athens and laid the groundwork for Western civilization were shaped under his leadership.

One of Pericles' greatest legacies is his contribution to democracy. Although Athenian democracy was not perfect, and large parts of the population, such as women and foreigners, could not vote, a system was created in which a significant portion of citizens had direct influence on politics. The democratic institutions developed under Pericles formed the cornerstones of Western democracy and influenced many of today’s political structures. In a sense, Pericles can be called a father of liberalism.

Socrates held an ambivalent view of Pericles. While he praised him as a “good man” and “wise in the affairs of the city” in the Meno, he felt Athens’ artistic and commercial splendor did not produce better souls. The largesse (paying off the public with reforms, benefits, and generous spending) of Pericles, Socrates argued, made Athenians lazy and entitled.

In the Gorgias dialogue, Socrates criticized rhetorical speech as an unworthy profession and claimed that Pericles misled the public through his speeches, drawing Athens into unnecessary wars. Above all, Socrates controversially continued to attack democracy itself as fundamentally flawed. Despite this, Pericles respected Socrates and never censored him, unlike later democrats such as Anytus.

Roman writers admired Pericles for his political skill and for creating an archetypal city-state that Rome would emulate. However, they also scrutinized his manipulation of public wealth, seeing it as a vulgar trait more associated with tyrants propped up by plebeians.

Thucydides’ accounts of Pericles continued to inspire republican projects, especially as the Middle Ages drew to a close. Officials and scholars in medieval Italian republics like Florence, Pisa, and Venice referenced Periclean reforms and sought to emulate his moderation. By the Enlightenment, Voltaire had proclaimed Pericles a model of the benevolent ruler. Others, like Machiavelli, viewed him as an exemplar of cunning political skill.

John Adams and Alexander Hamilton discussed the strengths and weaknesses of Periclean rule in The Federalist Papers and other foundational works of American civic design. Detailed studies of Pericles’ legal innovations contributed to many aspects of the civic framework of the United States.

Nietzsche, though contemptuous of democracy, gave a positive appraisal of Athens’ Golden Age, especially its age of mousike. He rejected the traditional Socratic reading of Athens' decline as due to moral decay, calling it bigoted and shortsighted. Instead, Nietzsche celebrated the Athenian spirit of creation and destruction as a model of life-affirmation.

Pericles’ reforms inspired the development of democratic ideals not only in Athens but also in later European states and the modern world. His vision of a people directly participating in governance became a key tenet of Western political thought.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Plutarch, Lives

Life of Pericles, Plutarch

History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides

Bibliotheca Historica, Diodorus Siculus

Pericles of Athens, Donald Kagan

CREDIT

Thersthara

[TG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe