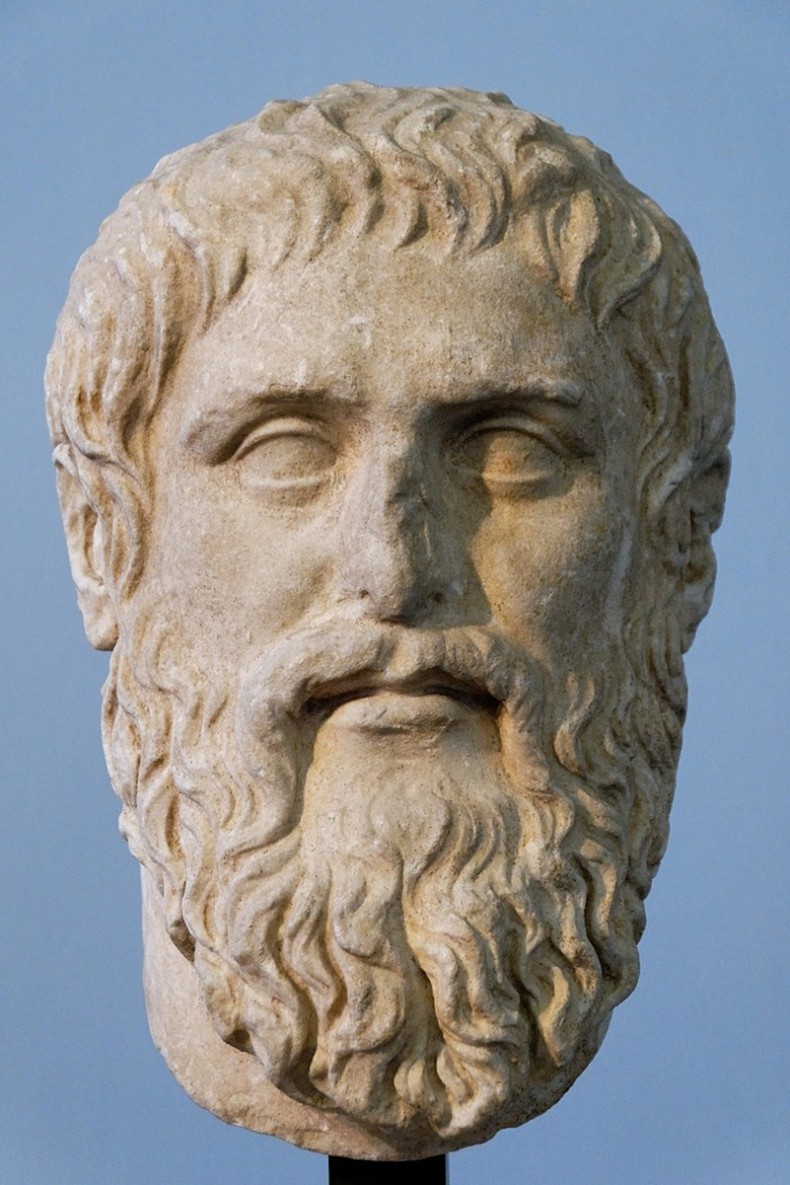

Plato

Great One of the Domains

Plato is known as the legendary philosopher from whom all formal disciplines arise. The aegis of his contentions and beliefs has influenced every strand of philosophical thought there is. The dialectic and dialogue arise from his representation of Aristotle. He also became the founder of the Platonic Academy, a profound and radiant institution in Athens that spread the cause of Greek philosophy to the four corners of the earth.

Aristocles, properly known by his divine name of Plato, was born in Aegina during the eighty-eighth Olympiad, on the day of modern November 21st (the all-important November 8th for Renaissance humanists). Ariston, his father, hailed from the Athenian deme of Kolytus and was a descendant of the legendary King of Athens named Kodrus. His mother, Perictione, was a descendant of Solon, the highly esteemed lawgiver of Athens, and was also a cousin of the tyrant Critias. Plato was born into a highly esteemed aristocratic family.

A legend states that Perictione became pregnant via a vision of Apollo (Azazel):

Σπεύσιππος δ᾿ ἐν τῷ ἐπιγραφομένῳ Πλάτωνος περιδείπνῳ καὶ Κλέαρχος ἐν τῷ Πλάτωνος ἐγκωμίῳ καὶ Ἀναξιλαΐδης ἐν τῷ δευτέρῳ Περὶ φιλοσόφων φασίν, ὡς Ἀθήνησιν ἦν λόγος, ὡραίαν οὖσαν τὴν Περικτιόνην βιάζεσθαι τὸν Ἀρίστωνα καὶ μὴ τυγχάνειν· παυόμενόν τε τῆς βίας ἰδεῖν τὴν τοῦ Ἀπόλλωνος ὄψιν· ὅθεν καθαρὰν γάμου φυλάξαι ἕως τῆς ἀποκυήσεως.

Speusippus, in the work titled Plato’s Banquet, Clearchus in Plato’s Encomium, and Anaxilaïdes in the second book On Philosophers, say that [as was told in Athens] Ariston attempted to force himself upon Perictione, who was beautiful, but was unsuccessful. And when he ceased his attempt, he saw a vision of Apollo, from which it was believed that she remained pure in marriage until she gave birth. 1

His family were cleruchs, colonists to Aegina who retained Athenian citizenship. The Spartan invasion of the island shortly after his birth forced Ariston back to Athens. Some months later, Ariston perished, and Plato was brought up by his stepfather Pyrilampes, his grand-uncle.

From a very early age, Plato was known for his prodigious memory and ability to perform mental feats unknown to other children; he was also known to work to extents that were inconceivable. His tutors, Speusippus and Dionysius, made Plato earn his intellect through severe tasks and difficult training regimens, a process that ultimately crowned his mental excellence and made it enduring.

During his youth, much like his associate Socrates, Plato excelled in all of the arts (mousike) to a notable extent. Of particular interest to Plato were the arts of poetry and playwriting, a skill that also helped him compose his dialogues. He acquired a status akin to a modern Poet Laureate of Athens prior to his late teens.

Later, he progressed into writing tragedies fashionable at the time and was said to be a choregus, the lead of a chorus. In fact, Plato first noticed the presence of Socrates not through family ties but through the latter’s creative association with the legendary playwright Euripides.

It was not only in this arena that he made a mark of extreme distinction: Plato was known as one of the finest sportsmen Athens had ever produced, largely through the tutelage of Ariston of Argos. At the Isthmian Games and Pythian Games, he engaged in many wrestling matches and participated in other sports, winning the vast majority of his bouts. One of Plato’s most famous sayings relates to his high esteem for sport and physical exercise:

μήτε τὴν ψυχὴν ἄνευ σώματος κινεῖν μήτε σῶμα ἄνευ ψυχῆς, ἵνα ἀμυνομένω γίγνησθον ἰσορρόπω καὶ ὑγιῆ. τὸν δὴ μαθηματικὸν ἤ τινα ἄλλην σφόδρα μελέτην διανοίᾳ κατεργαζόμενον καὶ τὴν τοῦ σώματος ἀποδοτέον κίνησιν, γυμναστικῇ προσομιλοῦντα, τόν τε αὖ σῶμα ἐπιμελῶς πλάττοντα τὰς τῆς ψυχῆς ἀνταποδοτέον κινήσεις, μουσικῇ καὶ πάσῃ φιλοσοφίᾳ προσχρώμενον, εἰ μέλλει δικαίως τις ἅμα μὲν καλός.

Neither should the soul move without the body, nor the body without the soul, so that by defending themselves, they may remain balanced and healthy. One who devotes himself to mathematics or any other rigorous intellectual pursuit should also provide movement for the body by engaging in gymnastics; likewise, one who carefully trains his body should, in turn, compensate by exercising the motions of the soul, making use of music and all forms of philosophy.3

Plato was known for his seriousness and gravity of character from a young age. He had a reputation for being stony-faced and, at times, difficult.

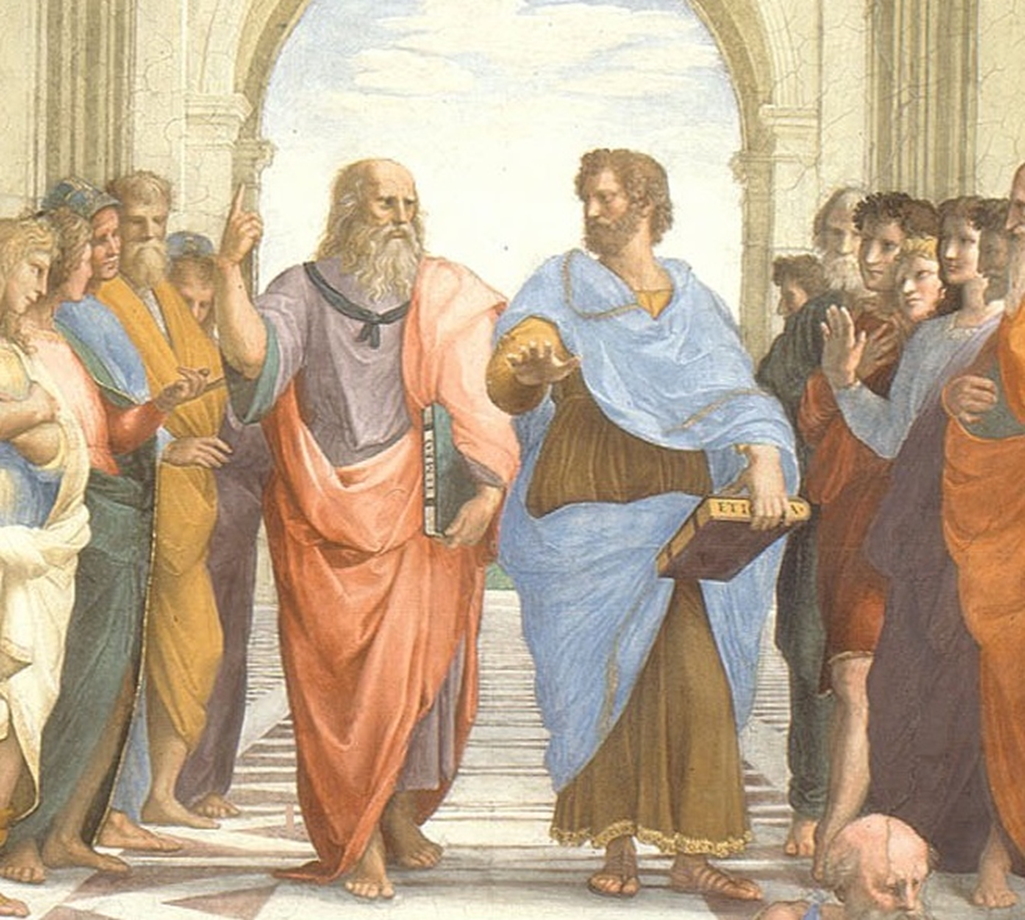

His first philosophical role model was Heraclitus, whose doctrines he studied at the Academy of Athens. Plato’s meeting with Socrates, whom he first observed outside the Theater of Dionysus, changed his life. The path he chose in studying under Socrates was supplemented by further study of Heraclitus from Cratylus, and of Parmenides from Hermogenes.

At first, Plato desired a position in politics. However, the instigation of violence and tyranny at the hand of Critias (Plato was his first cousin once removed), particularly in circumscribing Socrates, dissuaded him entirely from associating with the oligarchical Thirty Tyrants, despite the fact that a civic position was a certainty on account of his excellence. When the Tyrants were killed and deposed, the democratic regime of Athens eventually turned its ire toward Socrates. Experiencing the worst of both systems made Plato increasingly disillusioned with politics altogether.

The headband had long white tassles at the side

He fled Athens, departing with select disciples to Megara. From there, Plato journeyed to Cyrene to visit Theodorus to comprehend mathematical concepts, then to the Greek colonies in Italy to meet the Pythagoreans. Finally, he ended up in Egypt to learn certain doctrines from the priests of that country. Plato was also educated in many things by Epicharmus, a comic poet of some philosophical weight who refined his style. Later on, he made the acquaintance of Dion of Syracuse and attracted the ire of the tyrant Dionysius. At one point in his travels, Plato was even sold into slavery, being inches from death at Dionysius’ command. He was taken to Aegina, where a fellow philosopher luckily recognized him and paid for his freedom.

Who but a man with such an extreme life, and yet such solid self-possession in the face of it, could speak so firmly on all aspects of life itself? This also did not dissuade Plato from returning to Syracuse twice more while Dionysius still ruled the city.

Returning to the Academy of Athens, Plato sought to improve upon all of the developments of the Hellenic philosophers from Miletus, Athens, Syracuse, and beyond. Although some have claimed that Plato was dogmatic due to the strong statements woven into his texts, the refinement of his thoughts lay atop a great synthesis of many ideas. The purposes of his dialogues reflect this multiplicity of thought.

Οὗτος πρῶτος ἐν ἐρωτήσει λόγον παρήνεγκεν, ὥς φησι Φαβωρῖνος ἐν ὀγδόῃ Παντοδαπῆς ἱστορίας. καὶ πρῶτος τὸν κατὰ τὴν ἀνάλυσιν τῆς ζητήσεως τρόπον εἰσηγήσατο Λεωδάμαντι τῷ Θασίῳ. καὶ πρῶτος ἐν φιλοσοφίᾳ ἀντίποδας ὠνόμασε καὶ στοιχεῖον καὶ διαλεκτικὴν καὶ ποιότητα καὶ τοῦ ἀριθμοῦ τὸν προμήκη καὶ τῶν περάτων τὴν ἐπίπεδον ἐπιφάνειαν καὶ θεοῦ πρόνοιαν.

He was the first to introduce an argument in the form of a question, as Favorinus relates in the eighth book of his Miscellaneous History. He was also the first to propose to Leodamas of Thasos the method of analyzing a question. And he was the first in philosophy to name “antipodes,” “element,” “dialectic,” “quality,” as well as “the extended (dimension) of number,” “the flat surface of boundaries,” and “the providence of God.” 1

He ascended into the realm of truth during the thirteenth year of King Philip of Macedon’s reign. Plato’s stature was such that the King of Macedon himself immediately came to visit the Academy and pay respects. Many sanctuaries were subsequently built to the great philosopher in Athens, and Greek authors show him as being enrolled among the daimones.

Diogenes Laertius claims Plato devised his dialogues with distinct approaches and didactic purposes, to the point where there was a general system of several categories into which each dialogue could acceptably be placed. Specific exchanges by Plato were ambiguous and can even be said to be self-refuting. Others hinged on a sense of certainty and were filled with factual reasoning, and yet others flitted between both.

MORAL PHILOSOPHY

Plato equates virtue with knowledge and, although relying on accurate representations of what Socrates said and did, uses Socrates as a device to show how knowledge can lead to virtue. Certain dialogues such as the Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Protagoras, and Gorgias demonstrate how virtue is directly teachable, something that authors such as Terence Irwin have touched upon.

Meditative and rational understanding of these concepts leads one to greater knowledge, advancing into a higher dimension of being and knowing. Through continual repetition and reflection, an inner morality emerges, one that is separated from the often brutish demands of the ego.

FORMS

Following on from the discursive elaborations of virtue, Plato is most known for his Theory of Ideas (also known as Forms). He noted, drawing from the Pythagoreans, that mathematical and immaculate concepts, like a circle, can only be created, portrayed, and, in some ways, even imagined imperfectly by humans. The thought of a circle can wither away or be distorted. A drawn circle is always imperfect and can succumb to time when put on paper. Likewise, a circle fashioned from stone is never rendered as perfectly as the pure idea of what a circle is. Plato surmised that the perfect circle exists in the realm of Ideas.

The Pythagorean teachings demonstrated, nonetheless, that a perfect circle or triangle can only be accessed through reason, a process of thinking and logical reflection divorced from merely observing the world through the senses. This led Plato to believe there must be similarly perfect Ideas for concepts such as Beauty, Justice, and Fairness, of which humans, in their limited world, can only grasp imperfectly and intermittently, in acts and reactions, description, perception and sensual data, skill, knowledge, application, and so on. Any such application of the Idea in our realm is called “participation.”

The Theory of Ideas was not purely about the properties of objects and abstraction, however. Beholding a mass of imperfection, underdevelopment, and deviation from what he believed once was, Plato looked carefully at humanity. He used this to illustrate a point about the limited level of Being in comparison to the Gods, who are, in a sense, the perfected Form of humanity residing in or near the eternal Aether.

Why was this a point worth making indirectly? The idea bridged the gap between the increasingly impersonal, abstract concept of the perfect Monad created by the philosophers of Miletus, and the vulgar understanding of the Gods held by the masses of Antiquity, who often conceived of the Gods as having entirely human dispositions. He refers to this in the Eta Virtue of Astarte:

Plato then, when asked, pointed at the Heavens and said:

“The supernal realms are filled and rife with the Beauty of the Great God. In there, nothing is disharmonious, nothing is not measured, nothing is disproportionate.”

ALLEGORY OF THE CAVE

The Allegory of the Cave, the most famous example Plato utilized in his philosophy, follows on from the Theory of Ideas. Socrates explains to Glaucon that he should imagine a group of cave-dwellers chained by their ankles and necks to an inner wall for eternity, facing an outer wall. They observe shadows projected onto this outer wall by objects carried behind them, along the inner wall, by object-carriers who remain invisible to the chained dwellers. A fire behind the carriers creates the shadows that the cave-dwellers see, though they see neither the objects nor the fire. The carriers also name the sounds of the objects they carry, which the cave-dwellers assume must be coming from the shadows.

Only the philosopher, or divinely inspired man, exits the cave and is eventually able to comprehend the Sun, along with everything else, before returning to the cave to attempt to liberate the rest. The ignorant man, however, runs back to the cave, frightened and blinded by the Sun, and tells the others that the outside world is evil and hostile.

For Plato, comprehension of the divine Ideas and liberation from the state of the Andrapod was only made possible through meditation and education; without this, becoming like the ignorant cave-dwellers, or the one among them who rejects reality, was nearly inevitable. He used this example to impress upon individuals that life without the Gods is precarious.

The Sun is equated with the "child of goodness": it illuminates and spreads light, enabling the wise to see life as it truly is. Goodness is likened to illumination in the pursuit of knowledge. In addition to the Sun, there are also complex elaborations about Saturn, the star of the Sun, interwoven into this problem.

Many modern works, such as The Matrix, are aesthetic elaborations of this concept illustrated by Plato. Other works, like Nineteen Eighty-Four, are heavily influenced as well, creating universes to illustrate the adverse consequences of human-hating systems.

CULTURAL ASPECTS

Plato engages in certain criticisms of the representations of the Gods common in his time, finding them simplistic and, in a way, misleading. He understood that people could more easily grasp plays, tales, and cultural representations that corresponded to certain states of the human mind, but he warned of their potential to deviate from the true essence of what the Gods are.

The Guardian class of the Republic are advised to adhere to portrayals of the Gods that align with their spiritual advancement. This has led to the misunderstanding that Plato wished to ban all forms of creativity forever, which is, of course, ridiculous.

THE MODERN CONTEXT

Furthermore, there were many secrets to his teachings. Plato himself says that writing is a poor substitute for verbal instruction. Some of these, what Aristotle called the "unwritten doctrines", were only elaborated upon to his disciples at length and were deemed suitable only for an elect group. Others, such as meditative techniques discussed in the dialogues and in other manuals, have simply been altered, written out of history, or lie carefully obscured from view in the vaults of the enemy. Only parts of the Timaeus allude to these.

The perversion of Plato’s teachings during the downfall of Rome, via the efforts of infiltrators, the fashioning of Plato as a forerunner of Christianity by the Church, and the further appropriation of the Platonic dialogues after their reappearance during the Renaissance, was a major project of necessity for the Christians and their sponsors.

Yet even they had to admit, grudgingly, that something about Plato was not ordinary:

Hunc autem Platonem, quod iam in secundo libro commemoravi, inter semideos Labeo ponit…

Now this same Plato, as I have already mentioned in my second book, is listed by Labeo among the demigods… 2

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes Laertius

2City of God Against the Pagans, Augustine

388b-c, Timaeus, Plato

“Plato’s Myths”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Catalin Partenie

Vol. 4: Plato – The Man and His Dialogues, A History of Greek Philosophy, W.K.C. Guthrie

Plato’s Theory of Ideas, W.D. Ross

Plato’s Moral Theory, Terence Irwin

CREDIT:

Karnonnos [SG]

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe