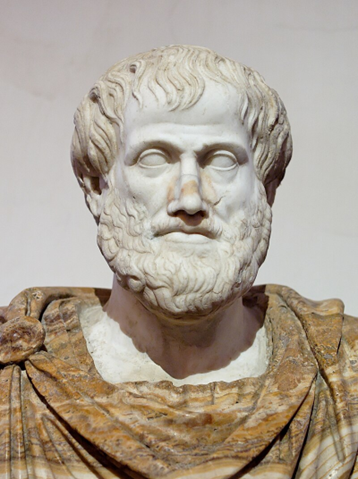

Aristotle

Master of Knowledge

The divine Aristotle’s name is a byword for knowledge and being learned: there is no thinker as influential across all the disciplines that exist. He taught and contributed to knowledge in more than thirty subjects, exhibiting an understanding of supernatural and mysterious caliber. For that reason, he is known as the Master of Knowledge.

At least one hundred and forty complete works full of his knowledge existed in Antiquity, reflecting his legendarily productive nature and prodigious intellect. Even in the fallen world inaugurated by Christianity and Islam, Aristotle was simply named the Philosopher by the majority of learned people, being indispensable to all branches of knowledge.

THE DIVINE YOUTH

He was born in Stageira, a city on the coast of Macedonia founded by Ionian settlers. Legend has it that Aristotle was descended directly from Asclepius via his father Nicomachus’ side. It is known that both of Aristotle’s parents died young; after this, he became the ward of Proxenus of Atarneus, his brother-in-law. During his later teenage years, Aristotle went to Pella, the capital of the nearby Kingdom of Macedon, during which he met representatives of the monarchy.

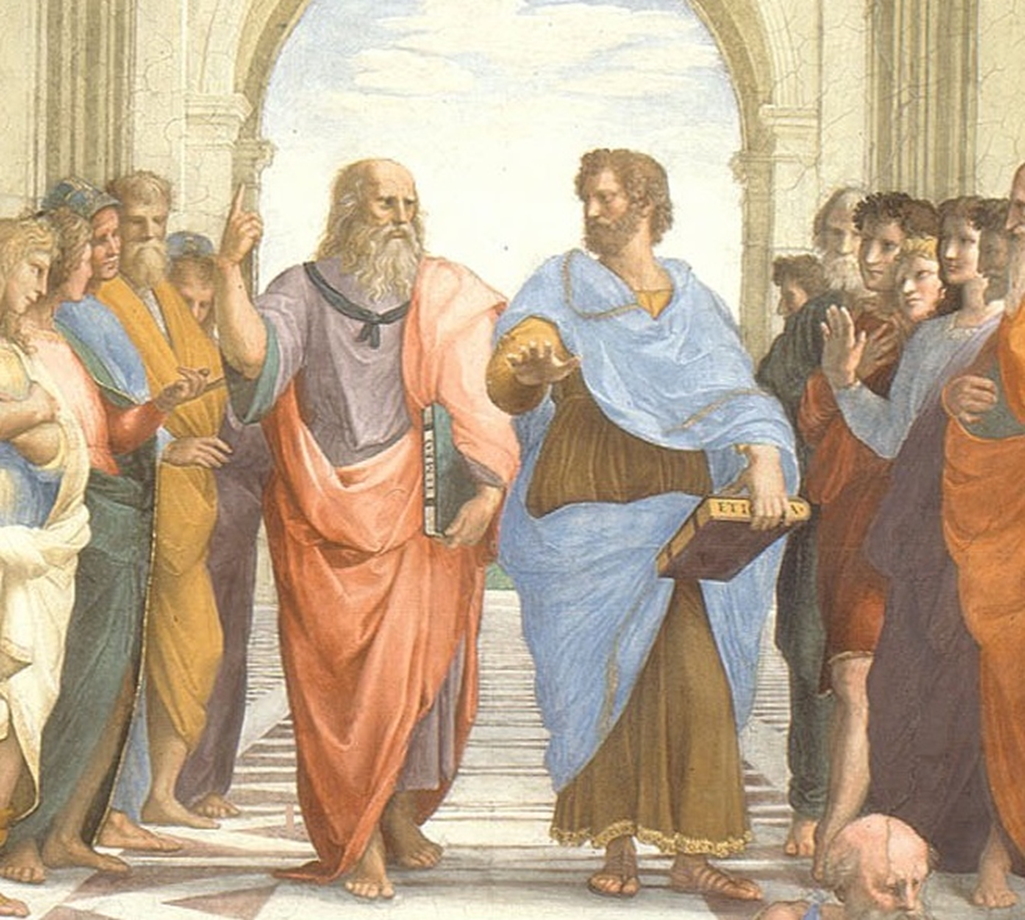

Hearing of the existence of a philosopher without equal in Athens, Aristotle decided to leave and attend the Academy of Plato there at around seventeen years of age. Greatly distinguished as a teacher and lecturer beyond compare, Plato himself came to name Aristotle the mind of the Academy.

During his twenties in Athens, he experienced the Eleusinian Mysteries, which he references in his lost works via other writers, describing them as something distinct from his usual acquisition of knowledge:

Φησὶ δὲ ὁ Ἀριστοτέλης ἐν τοῖς Ἀκροατικοῖς, ὅτι ἐν τῷ μυεῖσθαι οὐ μαθεῖν τι δεῖ, ἀλλὰ παθεῖν καὶ διατεθῆναι.

Aristotle says in his [esoteric] writings that, in being initiated (into the mysteries), one must not learn something, but rather experience something and be brought into a particular state.1

After the passing of Plato, Aristotle was dissatisfied with the teachings of Plato’s nephew, Speusippus. He separated himself from the Academy.

THE PATRON OF ALEXANDER

Although the King of Macedon, Philip II, had destroyed Stageira, Aristotle’s hometown, Aristotle chose to take up residence in Macedon as tutor to the Argead dynasty and the aristocracy. He established a school at Mieza at the Temple of the Nymphs, the remnants of which still stand today.

It is recorded that Aristotle publicly taught Alexander and his companions medicine, philosophy, morals, religion, logic, and art for a number of years. Impressed with the character the teacher was cultivating in his son, Philip even rebuilt Stageira itself in Aristotle’s honor. Following this, the philosopher created his first code of laws to ensure his native city would never be razed again.

Certain historians credit Aristotle with teaching Alexander mystical rites, deep matters of the occult, and the art of self-healing. Even in Antiquity, it was known that this was anything but a normal encounter and that Aristotle possessed aspects of divinity.

Although history has depicted him as a severe and contemplative figure, owing to his dry and complex style, Aristotle exhibited an unusual presence compared to the more austere Socrates and Plato. He was known in person for his love of jewelry and fine clothing, even possessing a distinctive hairstyle, as if he had shown up from another time or place entirely. Before his departure from this world, it is known he made an elaborate and complex will, indicating the eccentricities of his personality.

In conversation, many report that Aristotle’s statements were laconic yet often jovial, frequently getting to the heart of a matter, contrasting with his written works, which dissected every subject with extreme elaboration. Contemporaries found Aristotle to be a strange and semi-divine figure, someone who defied any stereotype and was sometimes difficult to understand. Unlike Plato, and much like Socrates, Aristotle chose to minister among the public, which did not make for an easy life.

Ἀναφέρεται δ᾿ εἰς αὐτὸν καὶ ἀποφθέγματα κάλλιστα ταυτί. ἐρωτηθεὶς τί περιγίνεται κέρδος τοῖς ψευδομένοις, “ὅταν,” ἔφη, “λέγωσιν ἀληθῆ, μὴ πιστεύεσθαι.” ὀνειδιζόμενός ποτε ὅτι πονηρῷἀνθρώπῳ ἐλεημοσύνην ἔδωκεν, “οὐ τὸν τρόπον,” εἶπεν, “ἀλλὰ τὸν ἄνθρωπον ἠλέησα.” συνεχὲς εἰώθει λέγειν πρός τε τοὺς φίλους καὶ τοὺς φοιτῶντας αὐτῷ, ἔνθα ἂν καὶ ὅπου διατρίβων ἔτυχεν, ὡςἡ μὲνὅρασις ἀπὸ τοῦ περιέχοντος [ἀέρος]λαμβάνει τὸ φῶς, ἡ δὲ ψυχὴ ἀπὸ τῶν μαθημάτων. πολλάκις δὲ καὶ ἀποτεινόμενος τοὺς Ἀθηναίους ἔφασκεν εὑρηκέναι πυροὺς καὶ νόμους· ἀλλὰ πυροῖς μὲνχρῆσθαι,νόμοις δὲ μή.

Τῆς παιδείας ἔφη τὰς μὲν ῥίζας εἶναι πικράς, τὸν δὲ καρπὸν γλυκύν. ἐρωτηθεὶς τί γηράσκει ταχύ, “χάρις,” ἔφη. ἐρωτηθεὶς τί ἐστιν ἐλπίς, “ἐγρηγορότος,” εἶπεν, “ἐνύπνιον.” Διογένους ἰσχάδ᾿αὐτῷ διδόντος νοήσας ὅτι, εἰ μὴ λάβοι, χρείαν εἴη μεμελετηκώς, λαβὼν ἔφη Διογένην μετὰ τῆς χρείας καὶ τὴν ἰσχάδα ἀπολωλεκέναι· πάλιν τε διδόντος λαβὼν καὶ μετεωρίσας ὡς τὰ παιδία εἰπώντε“μέγας Διογένης,” ἀπέδωκεν αὐτῷ. τριῶν ἔφη δεῖν παιδείᾳ, φύσεως, μαθήσεως, ἀσκήσεως. ἀκούσας ὑπό τινος λοιδορεῖσθαι, “ἀπόντα με,” ἔφη, “καὶ μαστιγούτω.

Some exceedingly happy sayings are attributed to him, which I proceed to quote.When asked, “What do people gain by telling lies?” he answered, “Just this: when they speak the truth, they are not believed.”

Reproached once for giving alms to a wicked man, he replied, “It was the man, not his character, that I pitied.”

He used to say to his friends and pupils, wherever or whenever he happened to be teaching: “As sight takes in light from the surrounding air, so does the soul from mathematics.”

Often, he remarked that the Athenians discovered both wheat and laws; but, though they used wheat, they made no use of laws.

“The roots of education,” he said, “are bitter, but the fruit is sweet.”

When asked, “What ages most quickly?” he answered, “Gratitude.”

When asked to define hope, he replied, “It is a waking dream.”

When Diogenes offered him dried figs, Aristotle noticed that the Cynic had prepared a barb if he refused to take them. So he accepted and remarked, “Diogenes has now lost both his jest and his figs.” On another occasion, he took the figs, lifted them up as one might lift a child, and exclaimed, “Great is Diogenes,” before returning them.

He said three things are necessary for education: natural endowment, study, and constant practice.

Upon hearing that someone was speaking ill of him, he said, “Let him strike me too, so long as I am absent.” 2

Aristotle experienced problems with certain rulers such as Antipater and the eventual usurper Cassander (one of his students) after Alexander’s army left Greece. He also came under scrutiny from the Athenians, who completely misunderstood his philosophy and viewed his association with Alexander with suspicion. He departed for Euboea and passed control of his school to Theophrastus, his successor, handing over many of his instructions. His writings later passed to the Library of the Kingdom of Pergamon and then back to Athens.

It is known that Aristotle was eventually regarded and promoted as a deity-like figure after his departure from the world. His followers gathered relics and even instituted a festival known as the Aristoteleia, which was celebrated even in the time of Justinian. On account of this divinity, Sulla also seized Aristotle’s writings and had them brought to Rome.

DISCLAIMER

Unusually for a denizen of antiquity, many of Aristotle’s works have survived to a considerable extent, due in part to the Church’s use of certain Aristotelian themes to support their rule. However, these works have still been altered, misrepresented, poorly transcribed, or horribly translated from the Ancient Greek. For example, it is known that certain source copies of the Politics diverge significantly in content. Parts of the Nicomachean and Eudemian Ethics are simply interpolated with each other at random. All of his works intended to be read in a literary format are missing.

In the Western Roman Empire, only select titles were available. The Eastern Empire maintained much of the corpus but often ignored the parts of Aristotle unrelated to theology and logic. Certain dialogues were available only in the Islamic world. Of the one hundred and forty known works of Aristotle, seventy or more either no longer exist or survive only in fragments, suggesting some sort of destruction or removal, given the maintenance of the so-called Corpus Aristotelicum. Structured books such as On Wealth, On the Pythagoreans, and On Monarchy, intended for a reading audience, along with dialogues like the Symposium, Eroticus, and Eudemus, are all missing from the surviving works.

One of the documents attributed to Aristotle that is not part of the medieval collection is the Constitution of the Athenians, discovered as a papyrus in Egypt during the late Victorian period. There are many missing writings by Aristotle: of the constitutions for specific states, one hundred and fifty-one are still unaccounted for.

Even in his extant writings, Aristotle often asserts that he does not know everything and that what he is putting forth is an experiment in thinking rather than a final and definitive conclusion. Theologians, astronomers, scientists, and others have misrepresented his studies as complete and authoritative since the Middle Ages.

ANALYSIS AND CATEGORIZATION

For Aristotle, analysis was divorced from pure reason alone; it required observation and the collection of evidence to formulate conclusions, the foundation of scientific thought. He used both deduction and induction to achieve this, rather than relying exclusively on either method.

Believing that areas of knowledge should be segmented into specific categories for ease of use, Aristotle introduced the idea of classification into the sciences and other disciplines.

LOGIC

Aristotelian logic is widely recognized as the foundation of logic in scientific thought, the basis of formal logic as a field:

ARISTOTLE created the science of logic, this is simple historical fact. For him, it was not merely one of the branches of learning, whether theoretical, practical, or productive, but an instrument all must use to reach true conclusions. His commentator, Alexander of Aphrodisias, rightly called logic an organon, or tool, and since the sixth century A.D., the word has been used as a general name for the logical treatises. 3

His work Prior Analytics is the first extant study of logic and treats it as the study of argument: a set of true or false statements leading to a true or false conclusion.

He introduced symbols, known as variables, to represent the subjects of arguments to avoid confusion. This was a novel development that allowed for more complex and systematic arguments. One of Aristotle’s enduring contributions is the syllogism, composed of a subject, predicate, operator, and a middle term, producing a relationship that demonstrates the validity of an argument. For example:

Premise 1:

Snakes have no legs. [Every A is in relation to B]Premise 2:

A python is a snake. [C is A]Premise 3:

Pythons have no legs. [C is B]

There are many complex nuances to syllogistic argumentation, applicable across all forms of learning. For the vast majority of philosophy’s history, logical argumentation depended on Aristotle’s formulations, only being even remotely superseded in the 19th century.

OPTICS

Aristotle was a major pioneer in understanding the nature of vision. Many of his observations still hold up today. He rejected the idea that vision occurs through rays emanating from the eyes, instead advocating for a theory of "intromission," where the eye passively receives light and color. Modern optics confirms this: vision indeed involves light reflecting off external objects and entering the eyes.

Integrating this with his philosophical system, Aristotle emphasized the importance of a transparent medium, such as air or water, between the object and the eye. He proposed that light transforms the medium from potentiality into actuality, enabling vision.

ETHICS

Aristotle asserted that just as the function of fingers is to manipulate matter physically, the proper function of a human being is to attain excellence and union with higher powers. One must become ethical through meditation, contemplation, and the practice of virtue, not merely by obeying spoken or written rules. Although Aristotle affirmed the usefulness of laws and moral codes, his emphasis on practice and habit means that ethics must be "lived out" rather than merely memorized or legislated.

Virtue must be coupled with discernment. Aristotle was careful not to apply the same standard to every situation. The ideal behavior in defending one’s state in war is not the same ideal used in writing a great play or raising a child. Compared to the rigid morality systems of the Torah, Bible, and Qur’an, which he would likely view as systems of spiritual slavery, Aristotle understood human nature and the path of proper evolution.

THE GOLDEN MEAN

In both the Eudemian and Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle reiterated and expanded on the concept of the Golden Mean, a philosophical idea that Socrates had discussed in the Dialogues. Aristotle observed that many ethical problems arise from deficiency or excess. For example, some people are overly flattering, while others are vulgar or aggressive. The best qualities, depending on the situation, lie between these extremes.

Aristotle considered the ideal individual to have mastered the four virtues traditionally translated as phronesis (prudence), dikaiosyne (justice), andreia (fortitude), and sophrosyne (moderation). These terms are not easily translated into English, particularly as Christianity has distorted their meanings, but they all relate to the temperance virtue of Apollo. Mastery of these requires living one's life consciously, meditating, and staying close to the Gods.

THE IDEAL STATE

Unlike Socrates and Plato, Aristotle was not fundamentally pessimistic about mass participation in government. He believed that groups of people, so long as they were not "utterly degraded", could often make better judgments than most individuals. When done properly, this form of government is a polity; when done poorly, it degenerates into what he called a bad democracy (later reformulated by Polybius as ochlocracy).

Similarly, monarchy was acceptable if led by a wise ruler, but otherwise devolved into tyranny. Aristotle deemed tyranny contemptible and dangerous, as the power of a wicked monarch cannot be checked, and any ruler violating a divine oath was in serious error.

In Politics, Aristotle argued that the three systems of governance were often misunderstood. He distinguished them not by the number of rulers but by whether the rulers served the common good. He developed multiple classifications of democracies and oligarchies based on Greek political systems he observed.

He warned against democracies led by demagogues who flatter a degraded populace:

This state of things is brought about by the demagogues; for in the states under democratic government guided by law a demagogue does not arise, but the best classes of citizens are in the most prominent position; but where the laws are not sovereign, then demagogues arise; for the common people become a single composite monarch, since the many are sovereign not as individuals but collectively. Yet what kind of democracy Homer means by the words ‘no blessing is the lordship of the many,’ whether he means this kind or when those who rule as individuals are more numerous, is not clear.

However, a people of this sort, as being monarch, seeks to exercise monarchic rule through not being ruled by the law, and becomes despotic, so that flatterers are held in honor. And a democracy of this nature is comparable to the tyrannical form of monarchy, because their spirit is the same, and both exercise despotic control over the better classes, and the decrees voted by the assembly are like the commands issued in a tyranny, and the demagogues and the flatterers are the same people or a corresponding class, and either set has the very strongest influence with the respective ruling power, the flatterers with the tyrants and the demagogues with democracies… 4

Aristotle concluded that the best-designed state rests on the soundness of its constitution, a view that influenced both the Roman Republic and the founders of the United States. Following the principle of the Golden Mean, he believed the ideal state would be led by a self-sufficient middle class, in contrast to states of "slaves and masters" resulting from class warfare.

The broader point is that although both the wealthy and the poor aim toward the good, their ignorance leads to destructive extremes. Just as an individual may stray from virtue, so too may a state become corrupt.

Aristotle was influenced by the rise of Macedon and the hegemony of Thebes. He saw Thebes as an oligarchy with limited popular institutions and was impressed by the dynamic monarchy of Macedon, where he tutored Alexander. Though he respected Athens deeply and its democratic system, he acknowledged its decline and its many flaws.

BIOLOGY

Aristotle is considered the father of biological sciences, having laid the groundwork for animal classification. He identified key differences between vertebrates and invertebrates and described around 500 species of birds, mammals, fish, and insects in History of Animals and Parts of Animals. Far ahead of his time, he concluded that whales and dolphins are not fish, while sharks and rays are.

Charles Darwin credited Aristotle as the Father of Biology. Many of Aristotle’s observations were only confirmed centuries later through microscopes and histological methods, for instance, his claim that the heart of an embryo forms first. These insights later inspired Galen, al-Razi, Leonardo da Vinci, and Paracelsus to conduct their own anatomical studies.

POETRY AND DRAMA

In Poetics, Aristotle defined drama as mimesis, or imitation of life. Drama, in this view, presents universal truths while allowing for abstraction and fantasy, stimulating contemplation in the viewer. Confronting one’s values or seeing challenging material can inspire transformation.

However, Aristotle insisted that one function of art should be educational and enriching, not "art for art’s sake." Muslim commentators like Avicenna misinterpreted this as promoting religious dogma, a distortion that entered medieval Europe and led to strict religious censorship of plays until Shakespeare’s time.

METAPHYSICS

In Metaphysics, Aristotle explores the nature of reality. He introduces ousia (substance) as the primary category of existence and distinguishes between form (essence) and matter (what something is made of).

This leads to his theory of hylomorphism: all physical things are composites of matter and form, in contrast to Plato’s dualistic theory. He also introduces potentiality and actuality, explaining that things exist in potential until fully realized. At the highest level of reality, Aristotle posits the Unmoved Mover, a purely actual, non-material entity responsible for motion and order in the universe.

In Physics, Aristotle studies nature and change, positing that all motion arises from four causes:

- Material cause: what something is made of

- Formal cause: its defining structure

- Efficient cause: the agent of change

- Final cause: its purpose or end

Unlike modern physics, which relies on mathematical laws, Aristotle saw nature as teleological, a system moving toward inherent ends. He distinguished between natural motion (e.g., fire rising) and violent motion (caused externally).

Much of this is misunderstood due to poor translations or theological distortions. Even Galileo and Newton worked from scholastic interpretations of Aristotle, not always from his original texts.

Metaphysics and Physics are deeply linked and his theory of being underpins his views on motion and change. His teleological model shaped medieval philosophy, especially in Scholasticism, and continued to influence debates in science and metaphysics.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Dio letters, Synesius

2Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes Laertius

3Aristotle, John Ferguson

4Book 4, Politics, Aristotle

Aristotle the Philosopher, J. L. Ackrill

Aristotelian Philosophy: Ethics and Politics from Aristotle to MacIntyre, Kelvin Knight

CREDIT:

Karnonnos [SG]

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe