Al Razi

Polymath

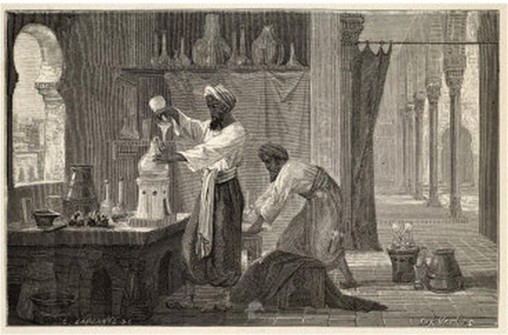

Al Razi (Rhazes) stands as one of the most competent doctors, scientists and physicians in history, a polymath of gargantuan intellectual power. Blazing a trail through medicine and the early study of chemistry, his life was marked by achievement. Writings by him on many subjects became influential.

His contributions to science and medicine were profoundly unique and became influential in Europe and India, redefining the role of the doctor and founding the field of formal pediatrics. Yet it was his philosophical beliefs inherited from Plato that marked him out for danger in his lifetime. Hounded in religious controversy in large part because of his unorthodox theology, these incidents rendered him the black sheep of the early Islamic era.

DOCTOR OF DOCTORS

Al-Razi’s reputation as one of history’s great physicians rests on his clinical acumen and comprehensive medical writings. He served as head of hospitals in Rayy and Baghdad, where he emphasized empirical observation and patient care.

He was unafraid to challenge classical authorities like Galen when evidence demanded so, a trait exemplified by his systematic critiques and case studies. Some of his contributions effectively founded new fields and introduced novel practices in therapy and medical ethics.

Al-Razi meticulously recorded patient case histories and symptoms, using them as a basis for diagnosis and treatment. His clinical notes in works like al-Hawi show an outstanding ability to isolate superficial symptoms of disease, prognosticate outcomes, and link symptoms to changes of the body.

He insisted on verifying theories through practice, even conducting one of history’s earliest clinical trials in comparing treated and untreated groups. For example, to test blood-letting in meningitis, he divided patients into two groups, bleeding one group and not the other; observing that only the unbled group progressed to fatal meningitis, he concluded the treatment’s efficacy.

One of al-Razi’s most celebrated medical discoveries was distinguishing smallpox from measles which were diseases often confused before and after him.

In his treatise Kitab al-Judari wa al-Hasbah (The Book of Smallpox and Measles), he carefully described their differing clinical courses and rashes. This was the first scientific description

recognizing these as separate illnesses, and he provided guidance on their diagnosis and treatment. The accuracy and originality of this work were lauded by the World Health Organization,

which called it “the first [sic] scientific treatise”

on infectious diseases...

Al-Razi is often regarded as a founder of pediatrics. He authored Diseases of Children, the first monograph treating pediatrics as an independent field. In it he catalogued childhood illnesses and their treatments, recognizing that children require specialized care and observation.

MEDICAL DESIGN

As a physician-alchemist, al-Razi advanced pharmacy by introducing new medicinal substances and preparations.

He was also among the first to apply distilled alcohol as a medicinal antiseptic and solvent, having distilled ethanol himself. Al-Razi’s emphasis on drug efficacy and dosage is evident in his writings he devoted sections of his encyclopedic works to pharmacology, discussing the strength and methods of preparation.

He refined and popularized pharmacy tools like mortars, flasks, and spatulas for compounding medications, effectively setting standards for pharmaceutical practice. Moreover, his treatise Bur’alSa’ah (“Cure in One Hour”) listed quick-acting remedies for common pains (headache, toothache, colic, etc.), reflecting his practical focus on relieving suffering promptly.

Al-Razi applied scientific thinking to public health and hospital design. Famously, he chose the site for a new Baghdad hospital by hanging pieces of meat around the city and observing where they decayed slowest, reasoning that the location with the cleanest air would promote healing.

As chief physician, he organized the hospital with separate wards for different diseases and emphasized hygiene and ventilation. Notably, al-Razi is credited with establishing the world’s first dedicated psychiatric ward for the care of mentally ill patients in Baghdad.

He treated mental illnesses as medical conditions rather than supernatural afflictions. The physician wrote that mental disorders have physiological causes, not demonic origins. This was linked to his true religious beliefs as he wished to undermine Islamic influence.

CHEMIST

Al-Razi’s experiments led to the discovery or first clear documentation of several important substances. He is often credited with discovering sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄), the powerful “oil of vitriol” produced by dry distillation of minerals. This acid became a staple of chemical laboratories in later centuries. He also obtained ethanol (ethyl alcohol) as noted, and recognized its solvent and antiseptic properties. These two – sulfuric acid and ethanol – are counted among the most significant chemical discoveries of the medieval period. Beyond these, al-Razi’s writings indicate he produced or utilized nitric acid and muriatic (hydrochloric) acid, as well as various salts and metallic compounds.

He manipulated arsenic and sulfur extensively; his Sirr al-Asrar gives detailed instructions for the manipulation of arsenic and sulfur, likely describing methods to obtain arsenic oxide and distilled sulfur or sulfide compounds. He also invented medicinal and practical products: for example, recipes for making soap from vegetable oils and alkalis are attributed to al-Razi, as is the preparation of antiseptic substances for wounds. By separating chemical facts from folklore, al-Razi amassed a body of practical chemical knowledge.

Al-Razi wrote numerous books on alchemy, of which two are especially famous. His alchemical magnum opus is Kitab al-Asrar (“The Book of Secrets”), later expanded as Sirr al-Asrar (“The Secret of Secrets”). In these works, al-Razi systematically describes the substances, apparatus, and operations of alchemy. He lists and characterizes raw materials – everything from minerals and metals to plants and animal products – and then details the equipment needed for chemical experimentation (stills, bellows, crucibles, etc.). He provides step-by-step procedures for conducting experiments, including the preparation of compounds and reagents. The Secret of Secrets in particular compiled much of his earlier work, becoming a comprehensive guide to practical alchemy. These texts were highly influential; they were translated into Latin (as Liber Secretorum) and circulated widely among later alchemists. Another notable treatise was his refutation of al-Kindi’s skepticism of alchemy. The philosopher al-Kindi had written dismissing the possibility of transmutation; al-Razi, a firm believer in the potential of alchemy, countered with arguments defending the art. Unfortunately, only fragments of this refutation survive through later citations. Nevertheless, it shows that al-Razi engaged critically with theoretical questions of alchemy’s validity, not just its operations.

PHILOSOPHY

Al-Razi was also an original philosopher, though much of his purely philosophical writing survives only in quotations by later authors. His outlook was marked by strong rationalism and an independent spirit of inquiry. He delved into questions of metaphysics (the nature of the universe and soul), ethics, and the philosophy of religion. In many respects, al-Razi’s philosophy broke with both Greek-influenced Islamic thought of his time and orthodox religious doctrine, making him a controversial figure. Nonetheless, his ideas on reason, the soul, and ethics were influential and illustrate the breadth of his intellect beyond medicine.

METAPHYSICS

Influenced clearly by Plotinus and other Platonic authors in circulation in the 9th to 10th centuries, Al-Razi proposed a bold cosmological theory involving five

eternal, uncreated principles:

God, Soul, Matter, Time, and Place. According to reports of his lost book on metaphysics, he argued that the cosmos as we know it emerged from the interaction of these five eternal realities.

In this scheme, only God and Soul are active and alive, while Matter is passive, and Time and Place are neutral contexts. Al-Razi’s scenario to explain creation is a unique theodicy

(justification of divine goodness despite evil): The Soul, in its primordial state, foolishly desired to mix with Matter, craving a corporeal existence. This impulsive act initiated the

creation of the world , “the Soul conceives a desire to be mixed with matter”,

resulting in a cosmos that contains both good (due to God’s design) and great

suffering.

The imperfections and pains of life are thus explained as consequences of the Soul’s error in blending with Matter, not failures of God. Al-Razi used analogies of a wise father letting a foolish child learn from mistakes to illustrate why God permitted this to happen. God also gave the Soul the gift of intellect (aql) which is human ability to reason as a guide to help it eventually recognize its mistake and strive for liberation from matter. This cosmology was radically different from the orthodox Islamic view of creation from nothing.

Likewise, time and space, he asserted, could not be created since any creation must occur in time and in a place. These ideas put him at odds with other Islamic philosophers who followed Aristotle. Later thinkers like al-Biruni and Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (no relation) criticized the five eternals as heretical. Nonetheless, al-Razi’s cosmological pluralism was a strikingly original attempt to reconcile the existence of evil with a benevolent God’s creation, and it highlights his commitment to following reason wherever it led, even against theological consensus.

Perhaps the most contentious aspect of al-Razi’s philosophy was his stance on religion and prophecy. He held an unusually critical view of revealed religion, asserting the primacy of reason over blind faith. According to his opponent Abu Hatim al-Razi who was assigned to debate his lack of orthodoxy, al-Razi questioned the need for prophets at all.

His argument was that God gave all human beings the faculty of reason (aql) to discern truth and morality, so it would be unjust and irrational for God to select only certain individuals (prophets) to receive divine knowledge. If guidance is truly important for everyone, God would make it available to each person through reason, rather than through a handful of prophets, a process which had in fact led to conflicts and schisms among their followers. Al-Razi equated slavish acceptance of religious doctrine on authority (taqlid) with intellectual laziness, a particularly dangerous viewpoint that got him hunted down.

He maintained that individuals must use independent reasoning to determine their beliefs and goals. Reportedly, he also rejected specific religious concepts like scriptural miracle stories and anthropomorphic descriptions of God, finding them philosophically problematic. These views, if accurately reported, were outrageously heretical to many contemporaries. Some later biographers, embarrassed by this irreligion, claimed such statements were forgeries by his enemies. However, the consistency of the critique with al-Razi’s general exaltation of reason lends credibility to the accounts. It fits with his medical outlook (favoring personal investigation over deferential acceptance of Galen) as another example of his intellectual independence. In sum, al-Razi extended his rationalism to the sphere of religion: he was a freethinker who valued an individual’s reasoned understanding above tradition or authority in all domains.

Due to being destroyed by Islamic authorities, most of al-Razi’s philosophical writings are lost, but a few survive or are known by title and summary:

Spiritual Medicine was a work by him drawing parallels between medicine and ethics. Al-Razi offers guidance for “healing” the soul’s character and promoting virtue, much as a doctor heals the body. He discusses emotional moderation, the training of one’s habits, and the use of reason to overcome psychological ailments. This work provides insight into al-Razi’s moral philosophy and was likely written for a general audience to encourage virtuous living.

Philosophical Way of Life was a polemical work defending philosophy as the best guide to life. It was written as a reply to critics (like Abu Hatim) who attacked al-Razi’s views. In it, al-Razi explains and justifies his commitment to reason and philosophical ethics. He also clarifies misunderstandings about his cosmology and religious stance, arguing that a rational philosophical life is in harmony with God’s will (as he understood it). This text is fragmentary today, but its content is known through quotes in others’ writings. In it, he defended the philosopher’s life as superior to other ways of life, comparing the long-term benefits of wisdom to the immediate gratifications of sensual indulgence. He likely responded to accusations of impiety by explaining how his philosophy was compatible with a genuine, if non-traditional, understanding of God and piety.

On the Five Eternals was another postulated work that is referred to but has no title. This was Al-Razi’s treatise on metaphysics in which he expounded the doctrine of the five eternal principles. While the original is lost, its content is reconstructed from later critiques. In this work, al-Razi would have detailed his reasoning for positing co-eternal Matter, Soul, Time, and Place alongside God, and elaborated his narrative of creation and the Soul’s fall. It likely drew on Platonic ideas (e.g., the pre-existence of soul and the world of matter) but in novel form.

The bold ideas here made this one of his most famous (and infamous) contributions to philosophy.Fi Mahiyyat al-‘Aql (On the Nature of Intellect) and Fi’l-Nubuwwat (On Prophethood) were the most controversial and supposedly had him hunted down for. These titles are reported in bibliographies and may correspond to works where al-Razi discussed epistemology and prophecy. In such treatises he would have articulated his view that intellect is the supreme endowment of humans and the ultimate source of knowledge and guidance, downplaying or refuting the need for prophetic revelation. Although these works do not survive, their themes are preserved via reports of his debates and the Proofs of Prophecy written against him by Abu Hatim.

Room-temperature IQ individuals continue to claim al-Razi, while denying Islamic prophethood and the nature of Abrahamic religion as a whole, and being hunted for his beliefs, was a ‘Muslim.’ This shows the lack of any rigor in historical study and submissiveness to Islam, as well as Muslims cynical attempt to co-opt those they otherwise deem ‘heretical’.

Across all his philosophical endeavors, al-Razi championed reason, ethical integrity, and the pursuit of truth. He carried his critical and inquisitive spirit from medicine into philosophy, never hesitating to oppose if he believed logic and evidence were on his side. This unorthodox brilliance secured him a place as one of the most controversial and original thinkers of the time. While later scholars did not always embrace his more radical ideas, they engaged with them seriously, which in itself propelled intellectual progress. Al-Razi’s philosophical writings, especially on ethics and reason, echo through the works of later Islamic philosophers and even prefigure some early modern freethought in Europe.

CONCLUSION

Rhazes’ written works were scientifically invaluable and had enduring influence. His medical texts became standard references in West and East; his alchemical manuals guided generations of experimenters; and his philosophical ideas provoked debate long after his death. In summary, Abu Bakr al-Razi’s discoveries and excellence across medicine, chemistry, and philosophy mark him as one of the great contributors to human knowledge – a scholar who combined encyclopedic learning with experimental brilliance, and a humanist physician-philosopher dedicated to improving life through science and reason.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Abu Bakr Muhammad Ibn Zakariya Al Razi (Rhazes): Philosopher, Physician and Alchemist”, Samir S. Amr and Abdulghani Tbakhi, Annals of Saudi Medicine

1. H. D. Modanlou, Archives of Iranian Medicine 2008 – “A tribute to Zakariya Razi… an Iranian pioneer scholar.”

Abu Bakr al-Razi” (P. Adamson, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

“al-Razi… Recognized the need for an untreated control”, James Lind

“Rhazes’ Contributions to Alchemy and Pharmacy.”, Shiraz Medical Journal

Islamic Alchemists: Jabir and al-Razi, Tanner Sorensen

CREDIT

[TG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe