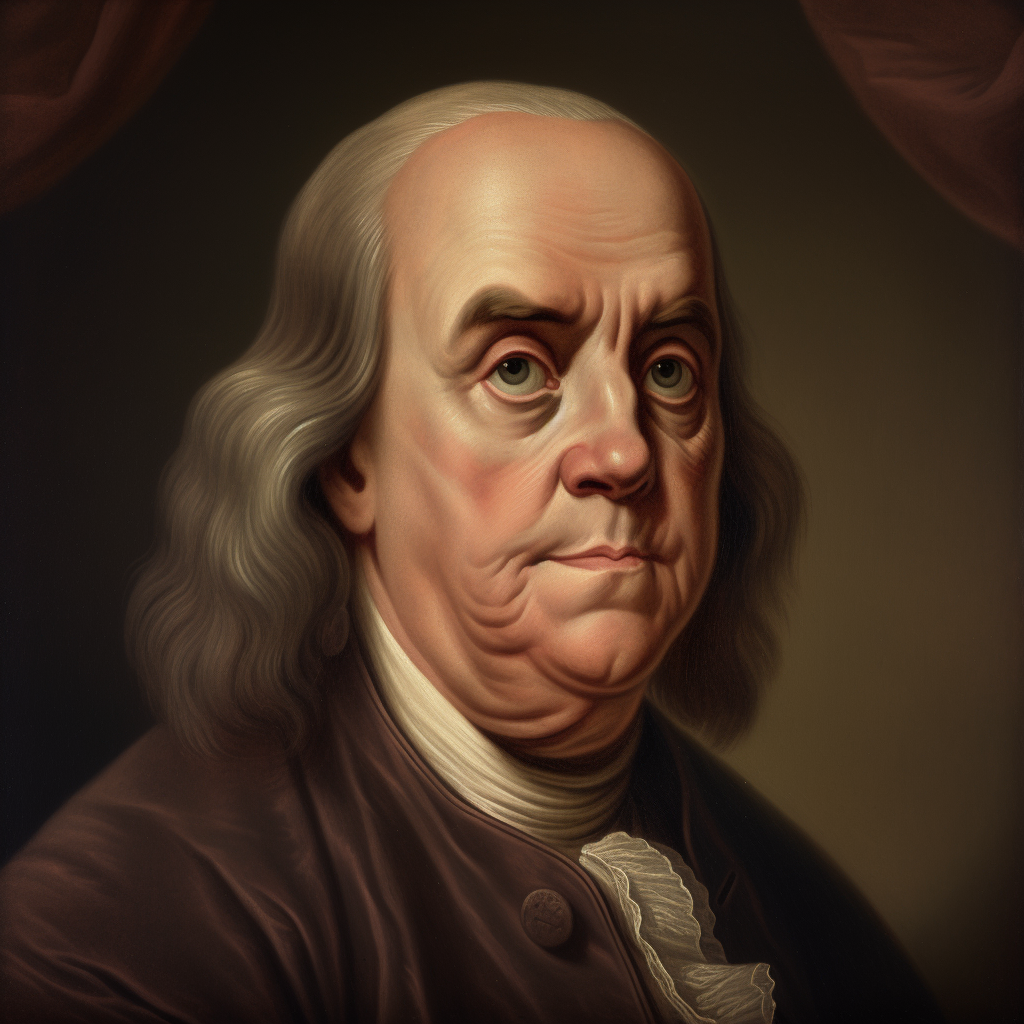

Benjamin Franklin

Polymath

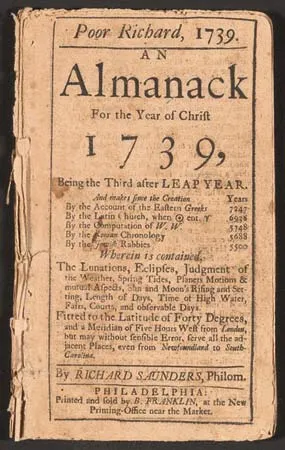

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) was one of America's foremost founding fathers, renowned for his diverse contributions as a statesman, inventor, scientist, printer, and diplomat. Born in Boston, Franklin rose from humble beginnings to become an influential figure in colonial America through his printing business, most notably publishing Poor Richard’s Almanack, which disseminated practical wisdom and moral advice. As a pioneering scientist, his groundbreaking experiments with electricity, notably the kite experiment, earned him international acclaim and solidified his reputation as a leading intellectual of his time. Franklin also invented numerous practical devices, such as bifocals, the Franklin stove, and the lightning rod, all of which improved everyday life significantly.

Politically, Franklin played a pivotal role in shaping early American history. He actively participated in drafting both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, serving as an elder statesman guiding debates with wisdom and pragmatism. His diplomatic skill was crucial in securing French support during the American Revolution, significantly aiding the colonies' victory over Britain. Franklin’s legacy extends beyond politics and invention, as he established numerous civic institutions including the University of Pennsylvania, libraries, and fire brigades, exemplifying his lifelong commitment to public service, education, and community improvement.

THE YOUNG INVENTOR

Benjamin Franklin was born in Boston, Massachusetts, January 17th, 1716, to parents Josiah and Abiah Franklin, both of which were devout Puritans. It's necessary to note the context here, as the Puritan household Franklin grew up in greatly influenced his later resistant attitudes against much of Christianity.

Puritanism can be best summarized as a sort of second-stage Protestant movement, or Protestantism within Protestantism. It was the belief of many English Christians of the era that the Church of England had began resembling the Catholic Church too heavily. There is some distinction to be made here, as people tend to mix the pilgrims and Puritans together (understandably so). The only real difference is that the pilgrims mostly wished to leave the Church of England behind altogether, whereas the Puritans generally sought reformation from within.

Regardless of the specifics, Franklin had both in his lineage, and even though his family's personal church was on the more liberal side (which isn't really saying much), for all intents and purposes it was still a stifling degree of dogmatic religiousness for anyone to grow up with.

It was the desire of Josiah Franklin that all his sons (he had a total of seventeen children between two wives), learn a trade. However, as if by a stroke of fact, Josiah only had enough money to send Franklin to school for two years, which denied him the opportunity to become a Christian clergyman. Given Benjamin was an extremely avid reader, his father ultimately decided to start him up on an apprenticeship with his older brother, James, who soon after founded the The New-England Courant, one of Boston's (and America at large's) first newspapers.

The paper was, unlike many of the papers running in colonial America at the time, really quite critical of the colonial government (and by extension, the Crown). It wasn't long before rumblings of sedition had began to gestate. Still, it's apparent that anti-British rule sentiment was fostered very early in Benjamin, and at the age of 15, desired to actually pen some articles himself.

James initially denied him, and Benjamin responded by writing under a pseudonym, Silence Dogood, the personage of a middle-aged widowess. James, impressed by the writing, and oblivious to the fact it was being written by his little brother, published the letters, which soon became the talk of the town, owing to their insight and generally a well-received sense of humor.

In one such letter, Franklin wrote in the spirit of the paper's message:

"WITHOUT Freedom of Thought, there can be no such Thing as Wisdom; and no such thing as public Liberty, without Freedom of Speech; which is the right of every man, as far as by it, he does not hurt or control the Right of another."

Eventually however, the ruse was up, and James grew furious. Soon after, a similar letter drew the ire of both the government and the clergy. James, despite his anger, denied revealing the true identity of the writer, and spent time in jail. Incensed, Franklin published heavy critique of the ruling powers in his brother's stead.

"Whether a commonwealth suffers more by hypocritical pretenders to religion or by the openly profane. But some late thoughts of this nature have inclined me to think that the hypocrite is the most dangerous person of the two, especially if he sustains a post in the government."

Despite threats by the local government, Franklin continued to publish until his brother's release. James had the idea of signing the paper into Benjamin's (now 17 years of age) name as to avoid further legal trouble. Benjamin showed a greater sense of cunning to his older brother, working his way around potential censorship by allegedly denouncing anything "hateful or malicious" and declaring the paper existed only for the sake of diversion and merriment. Most interestingly of all, Benjamin also declared the paper's new master was none other than Lord Janus. Assumedly in his mind, this was because Janus' ability to look in both directions either awarded the paper greater ability to read the current political landscape, or kept watch over their potential enemies from either side, though admittedly there may be yet more to this.

After the passing of several weeks, James' mood seemingly turned for the worse. Either he was bitter from his incarceration, or he was simply a jealous and oppressive man by nature, James began beating Benjamin, and reduced him back down to a mere apprentice, disregarding any sense of brotherly love and shrugging off any worth Benjamin had as a writer.

Towards the peak of the paper's local fame, Benjamin broke off from his apprenticeship and fled for Philadelphia. In the years meanwhile, the paper eventually grew to stagnate, having been variously engaged in longterm battles with the Mathers estate (as the paper had taken a hard stance against the proposed smallpox inoculation initiative being pressed by the Church and local bureaucracy) and the Puritans at large. James eventually went on to fold the paper, moving to Rhode Island and dying about 9 years after the publishing of the final issue in 1735.

Franklin was mostly dissatisfied with the opportunities present for him in Philadelphia, briefly emigrating to England, though under false pretense of a job offer. Instead, he worked a fairly mundane job in a deconsecrated Church in the Smithfield area of London, eventually returning to Philadelphia with an English merchant who employed him as a shopkeeper.

LEATHER APRON CLUB

It was in 1727 that Franklin formed the Junto (known otherwise as the Leather Apron Club). It was a sort of self-improvement society, drawing in a talent pool comprised of various people that were otherwise Franklin's friends or artisans from the local community. In Franklin's mind, his Junto was analogous to the English coffeehouse phenomenon; that being gentleman clubs which were often the stomping grounds for many of the Enlightenment movement's great thinkers and their subsequent ideas (I mostly note this as a sort of preamble to Franklin's later involvement with the Freemasons and Hellfire Club/s).

Following the death of the aforementioned merchant, Franklin went on to finally set up his own printing house with fellow Junto club member Hugh Meredith. Following this, the new printing house acquired and published The Pennsylvania Gazette. Franklin maintained his earlier jovial approach to publication, dabbling in satire and observational humor. On the whole, however, the earlier tone of agitation towards the British Crown continued, and Franklin fast began to cultivate respect as a local law reformer and moral commentator.

There's a lot of evidence to suggest printing in general was, and always had been, Franklin's darling trade. To him, the printing press was a sort of public duty, as he could instruct the

colonials on the virtues of good morality. Not because he saw himself as a moral paragon necessarily, but the contrary, as he was well aware of his lapses. This ties in to his Thirteen Moral

Virtues, developed a year before the formation of his Junto. The first instance, for example, was Temperance, or - to "Eat not to dullness; drink not to

elevation."

Point being, Franklin

grappled with obesity in his middle and later years, and enjoyed his food. However, he was aware of the benefits of eating lighter and spoke routinely on doing so as to maintain a clearer

mind.

To iterate further, he admitted to not live entirely by his own virtues, but at least tried to supremely live by one a week, leaving how well he performed at the others to fair chance. As a

personal observation, (and a somewhat ironic one given the two met and were seemingly friends by all accounts), this is honestly one of the better approaches to virtue I've seen. As Voltaire

said, Perfect is the enemy of Good. Oftentimes attempts at perfectionism will deny people the opportunity of realistic, steady growth. As Franklin put it, it was his attempt at proving himself

and society that brought him happiness in life. To quote: "I hope, therefore, that some of my descendants may follow the example and reap the benefit."

Back on the topic of his profession, Franklin moved to expand his printing business beyond Philadelphia, forging one of the (if not the first, though this claim is spurious) printing chain. A small majority of the English language newspapers were owned by Franklin outright. Interestingly, in perhaps what was a show of progressive thinking for the time, he employed the nation's first female printer, who went on to find apparent success. As one might imagine, with such a network in his grasp, Franklin did not have a hard time further illuminating the perceived injustices of British rule. Not so coincidentally, the building social unrest in the lead up to the Revolutionary War damaged much of said network.

In 1731, Franklin was initiated into the Masonic Lodge, which had apparently been something of a lifelong aspiration. In a mere three-to-four years, Franklin was already anointed a Grand Master, showing just how prominent Franklin had already become among his peers, despite beginning life arguably quite poor. To quote him on his perspective on Freemasonry at large:

"Masonic labor is purely a labor of love. He who seeks to draw Masonic wages in gold and silver will be disappointed. The wages of a Mason are in the dealings with one another; sympathy begets sympathy, kindness begets kindness, helpfulness begets helpfulness, and these are the wages of a Mason."

Notably, Franklin was responsible for the publishing of The Constitutions of the Freemasons, the first Masonic book in America. Having mentioned Voltaire earlier, it's also worth noting that Franklin presided over Voltaire's initiation into the French Loge des Neuf Soeurs Masonic Lodge. Being well-respected and a visitor of the European Lodges is fairly noteworthy, given that, based on everything I've read, the European Lodges were more vehemently anti-Christian in nature than the early American/Colonial Lodges, for the most part.

As a final remark on his earlier years, there's a few American cultural sayings that can be attributed to Franklin specifically, either in part or still quoted verbatim (taken the

aforementioned observational comedic writings noted earlier). Most people have heard of "a penny saved is a penny earned",

for instance, but the most contextually

interesting quotes are his

statements on faith. Obviously, again noting the context, "faith" here is specifically meant to invoke the faith regarded by his readers, that being Christianity.

"In the Affairs of this World Men are saved, not by Faith, but by the Lack of it.”

"The way to see by faith is to shut the eye of reason.”

I've harped on quite a lot about his work as a printer, which may seem slightly irrelevant in the grander Zevist sense, but this is frankly out of respect for his wishes and how he wanted to be remembered, which I think is important. Even after his years as a scientist and a statesmen, he continued to sign his name and occupation as B. Franklin, Printer. There was obviously a touch of humility to this, but the point still stands that, of all the things he'd accomplished and placed personal value on, it's fairly evident that his printing work still stood at the top.

MASON

Franklin’s prominence in Freemasonry made him a key figure in the fraternity’s early development in America. As one of the first Grand Masters in the colonies, he set a precedent for organization and cooperation. Franklin’s outreach to Henry Price in the mid 1730s helped integrate Pennsylvania Masonry under the umbrella of regular English Masonry, thereby strengthening the legitimacy and unity of lodges in America. He worked alongside other notable colonial Freemasons such as William Allen (who succeeded him as Provincial Grand Master in 1750).

In 1760, Franklin received further recognition abroad. While in London on colonial business, he was entered into the minutes of the Grand Lodge of England on November 17, 1760, as “Provincial Grand Master” of Philadelphia.

When Franklin arrived in France in 1776 as an American diplomat, he immediately engaged with the local Masonic community in order to encourage liberty and to ween American dependency off of England. In 1777 he was elected a member of the prestigious Parisian lodge “Loge des Neuf Sœurs” (Lodge of the Nine Sisters, under the Grand Orient of France).

On April 7, 1778, he assisted in the initiation of Voltaire, France’s most famous writer-philosopher and another Personality, into that lodge. The eyewitness accounts describe Franklin ceremonially giving the frail Voltaire the Masonic “kiss of peace” after initiation. He participated in the funeral of Voltaire the next year.

Under Franklins nominal leadership, the lodge undertook notable projects, such as creating a medal in honor of Voltaire and supporting the establishment of a Masonic Academy of sciences and the arts (the lodge was known for its patronage of learning). Franklin’s presence also likely helped the lodge navigate the delicate politics of the time; the American Revolution was in full swing, and many French Masons were sympathetic to the American cause. It is often suggested that Franklins fraternal bonds with influential Frenchmen smoothed the way for French support of the American Revolution.

In 1782 Franklin broadened his Masonic involvement by joining another Parisian lodge: on July 7, 1782 he became a member of the Respectable Lodge of Saint Jean de Jérusalem (St. John of Jerusalem), which elected him ‘Worshipful Master.’

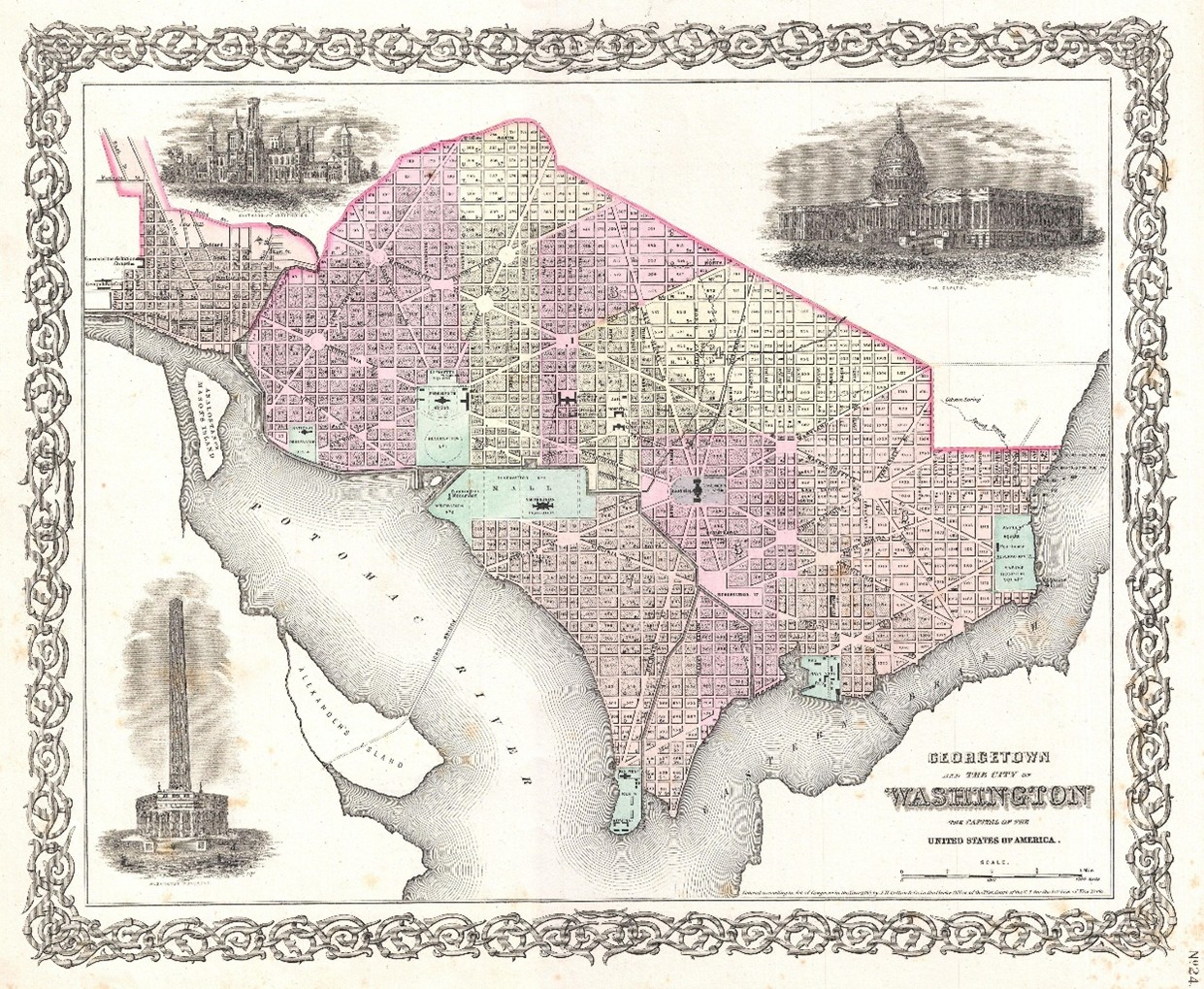

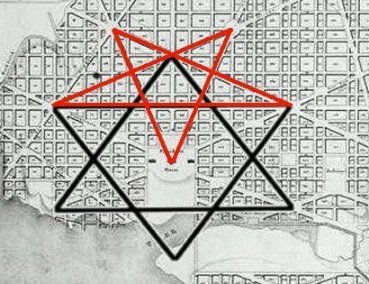

Franklin was indispensable to the American project as the French adored his rustic genius and amiability. His connections in France contributed to much of the occult design of the early United States. The District of Columbia was designed and built by Pierre Charles L’Enfant. He was a French architect and fellow Mason initiated into Holland Lodge No. 8 in New York City. L’Enfant came to America to fight against the British in the Revolutionary War, rising to become George Washington’s trusted ally.

Those who noticed the design propose that Washington D.C. was laid out as a terrestrial mirror of the sky, complete with more than thirty zodiac representations that align to actual constellations. At the heart of Pierre L’Enfant’s vision is Pennsylvania Avenue, running about a mile from the Capitol to the White House and oriented to track the rising path of Sirius. Viewed from Dupont and Logan Circles in the north, one can discern a set of interlacing avenues that form a star, featuring the White House at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Throughout the city, numerous buildings showcase zodiacal motifs. The National Academy of Sciences exhibits twelve zodiac reliefs on its metal doors, while the Federal Reserve Board Building adds two radiant glass renditions of these signs and the Library of Congress houses another five, among other prominent structures decorated with similar symbolism.

Franklin was involved in many design attributes of the nascent city.

STATESMAN

The 1740s marked Franklin's first major approaches into the scientific fields. In 1743 he founded The American Philosophical Society, for American scientists to discuss discoveries, learning and theories. It was around this time, and within these institutions that he first began to investigate electricity (which I'll regard at further length).

In truth, in terms of accomplishments in his post-printer years, there's almost too much to list even if you take his scientific work out of the equation. He partook in economic experiments to assist in regulating deflation/inflation. He established one of the first volunteer firefighting companies in America. He raised a militia during King George's War (the third of four separate conflicts within the French and Indian Wars mentioned at greater length in my Washington article). He and Thomas Bond (a noteworthy physician) established America's first colonial hospital in Pennsylvania. He helped establish the standards and model used by American colleges, and founded the College of Philadelphia (again, I'd like to note his model of college was remarkable specifically because it broke tradition of the time and required no religious examination to allow entry).

Most noteworthy of all perhaps, is his hand in establishing what ultimately became the United States Post Office, which still stands to this day.

All his work up to this point had earned him a political position, specifically as an agent of colonial interests in Britain. Much of his time was spent embroiled in longterm arguments with the Penn family, a Quaker family that was part of the British aristocracy who stood as the proprietors of Pennsylvania, of which Franklin was the key representative of. Penn's governing was not perceived well locally, though Franklin faced an uphill battle attempting to convince the court for fairer colonial terms, no doubt further flaring the sentiments he already had over British Crown rule.

There isn't too much to note on his further travels in Europe, though it went without saying he was well regarded just about everywhere he went and quickly became highly respected even by members of European royal families. Though, something that no doubt further colored his perception of the matters of tax, regulation and law applying to the colonies was the current situation in Ireland. He was the first ever American to sit with the members of the Irish Parliament proper, as opposed to simply being seated as a witness in the gallery. It was said he was greatly moved by the level of poverty and the general low class of living present in Ireland in 1771.

For added context, Ireland only gained legislative independence in 1782, and was still effectively under British governance even then, which, simplifying the matter down greatly, was something of a preamble to the Irish Famine. I note this, because it's said Franklin felt aware of where the British proprietors and their regulations/governance would lead the Colonies, and it was going to be into a situation that mirrored Ireland. Point is, Franklin (and the Founding Fathers at large), had very real world examples to avoid when drafting the specifics of the American independence.

Back in America, much Franklin's story at this stage mirrors what was written in the Washington article. For instance, he spoke at length about the apparent taxation that was set to be thrusted upon the colonies for the costs of the French and Indian Wars - nevermind that America had already shored up troops and supplies for the conflict.

Though, again citing much of what happened in Washington's life, it was the events of the Boston Tea Party (both the event itself and the circumstances leading up to it) that shifted Franklin's stance of someone who was willing to accommodate Crown rule to someone who was an American patriot. In response, Franklin penned one of his great essays, again following his personal tradition, with it being a work of satire.

The shape of Franklin's contributions to the Revolution itself were of a similar nature throughout, making use of the skills he had accrued over a lifetime. He ran an extremely effective propaganda campaign, and operated a surveillance network that prevented British espionage.

AMBASSADOR TO FRANCE

Perhaps most importantly, outside his signage and amendments to the Declaration of Independence, was his role as an ambassador to France, which utterly changed the fate of the war.

Firstly, he secured the French military alliance of 1778. As was noted in the George Washington's article, the French presence in the Battle of Yorktown was what assured a decisive victory, not to mention the economic backing, supplies, and the fact that Britain had to now contend with two enemies at once (not to mention already struggling with Spain and the Dutch). Moreover, this was the first formal recognition of the United States as an independent nation.

Secondly, he was present for the signing of the 1783 Treaty of Paris upon the conclusion of the war, which ended the conflict and recognized the colonies as their own independent power from Britain. Franklin was an extremely active Mason during his time in France, and he also influenced enough of France's intellectual aristocracy that Louis XVI signed the Edict of Versailles, which allowed non-Catholics access to basic civil rights without needing to convert.

I could really write an infinite amount on everything he did as a political figure, but this was really the main bulk of it. There's a reason why he was considered second in prestige only to Washington himself. After returning to America, it should be noted that Franklin freed his two slaves and committed himself as an abolitionist beyond that point. Franklin, interestingly for his time, seemed to hold a certain amount of respect for the Native Americans (though obviously took a hard stance against the tribes allied with hostile, anti-American powers).

To provide some quotes:

"Every Indian is a disciplined soldier. Soldiers of this kind are always wanted in the colonies in an Indian war; for the European military discipline is of little use in these woods."

"The Indian men, when young, are hunters and warriors; when old, counselors; for all their government is by counsel of the sages; there is no force, there are no prisons, no officers to compel obedience, or inflict punishment."

"Having few artificial wants, they have abundance of leisure for improvement by conversation."

In the wake of severe anti-Indigenous attacks undertaken by more extremist colonial factions, Franklin also said:

"If an Indian injures me," he asked, "does it follow that I may revenge that injury on all Indians?"

SCIENTIFIC WORK

The Leyden Jar Experiment - In 1746, Franklin heard about a German physicist by the name of Ewald Georg von Kleist who had created a device called the Leyden jar, which was a glass jar that could store an electrical charge. He may have been one of the first to attempt to connect the jars in a series, coming to propose what was known as the Single Fluid Theory, that being a proposition that electricity consisted of a single fluid that could flow between objects. From what I've read, he was the first to coin the notions of a "positive" and "negative" charge, and even was probably the first to coin the term "battery" to describe the setup he created using the Leyden Jars. Tesla himself, about a century later, noted that Franklin's work, despite the time, was not at all erroneous.

The Kite Experiment - This is perhaps what he's best known for outside of his work as one of the Founding Fathers. It seems obvious now, but, it wasn't understood at the time that naturally occurring lightning was a form of electricity. On the whole, however, electricity at this stage in history was mostly being used as glorified party tricks in exhibition halls. Franklin, however, had a yearning to actually contribute to humanity through his scientific work, and believed electricity was potentially the key.

On June 10th (or 15th, sources on this seem to vary), 1752, he decided upon his thunderstorm experiment. He attached to separate strings to a kite, one of silk and one of hemp, and secured a wire to the kite to conduct electricity. Against common misconceptions, he did not literally get struck by lightning during this, as he would probably have died on the spot. Though lightning wasn't well understood, he wasn't an idiot. By design, however, he was able to extract electric sparks from a thundercloud, whilst standing on an insulator. This obviously proved lightning was electrical in nature. Other, less intelligent individuals did go on to try and replicate the experiment and were subsequently electrocuted.

Following his experiments, Franklin invented the lightning rod to protect buildings from the damage caused lightning strikes. This probably doesn't need explanation, but the basic jist is, that a metal rod will conduct a possible strike and pass the current down a metal wire and to the ground, thus avoiding damage to the building's structure (or in the later sense, its electrical systems).

Outside of everything to do with electricity, his list of contributions are more massive than I suspected. To save on space, I'll list them as bullet points.

- Bifocal Glasses - Allowing those with more than one type deficiency in their vision to see properly courtesy of two distinct optical powers.

- Swimming Fins - Age 11 (which is remarkable in and of itself), he attempted to increase his swimming ability by attaching wooden panels to his hands. He attempted a sandal like flipper version, but found it too awkward, but it still set the groundwork for the modern day flippers.

- Franklin Stove - An improved fireplace that was more heat efficient and used less smoke.

- Flexible Catheter - Previously, rigid metal tubes were used for patients. Franklin's invention used hinged segments to allow for flexibility. This was a pretty big landmark for surgical science.

- Glass Armonica - If you've ever seen a musical performance where someone moves their finger around the rim of a series of half-filled glass bowls to produce sound, Franklin invented that too. People treat this with a degree of indignity for some reason but it's a legitimate instrument that's used in actual concerts.

- Daylight Savings - This is obviously conceptual but I figured I would note it anyway, even without it being adopted until the 20th century.

Lastly, he also contributed to several major studies on oceanography (one of which decreased a particular route time two weeks) and demographics (most notably, one study which suggested very early on that the colonies would grow a larger population than England in a fairly short amount of time, which further incensed England enough to restrict the colonies further as a means of attempting to keep the population low via economic oppression and regulations).

This isn't everything, of course, but just some of the more important things I found while reading. There's a myriad of smaller experiments (things like the heat absorption of darker colors versus lighter colors) but I figured these were the most relevant to write notes on.

CHRISTIANITY

Franklin's perspective is extremely nuanced. For instance:

"As to Jesus of Nazareth, my opinion of whom you particularly desire, I think his system of morals and his religion, as he left them to us, the best the world ever saw or is like to see; but I apprehend it has received various corrupting changes, and I have, with most of the present Dissenters in England, some doubts as to his Divinity."

This seems to be something of a recurrent trend with his statements. Franklin was Church critical, he did not consider himself a Christian and was openly a Deist (much like Washington himself), and he did not believe in Jesus' divinity. Franklin's God was referred to variously as Powerful Goodness (which reminds me somewhat of Plato's Form of the Good), the Infinite, and providence. By his own belief, it could be said that Franklin, in the context of what was necessary for the population at the time, believed in what you could call "generic religion". That is, a belief in a higher power, compelled morality, and a belief in the afterlife, though devoid of any specific dogma.

Obviously, the thing with the Freemasons was that they were a secret society, and the thing with secret societies is that they were, well, secret. Franklin's own approach to the occult, as such, is something I have found little trace of, as it seemingly happened only within the Masonic context behind closed doors.

For the sake of reference, I'll provide some further quotations to help make his viewpoint apparent.

On Church services:

"... Sunday being my studying day, I never was without some religious principles. I never doubted, for instance, the existence of the Deity; that He made the world, and governed it by His providence; that the most acceptable service of God was the doing good to man; that our souls are immortal; and that all crime will be punished, and virtue rewarded, either here or hereafter."

"I did not see any moral content in them. Therefore, I did not see any use in attending church at all. It was just a waste of time."

Regarding dogma at large:

"I think vital religion has always suffered when orthodoxy is more regarded than virtue."

Many movements used Jesus as a mask to hide their true beliefs (particularly certain Gnostic movements, and parts of the Knights Templar). For other movements, and perhaps relevant for Franklin, it's not as if many people of the era had access to much of the historical work that has made debunking a historical Jesus a five second internet search. For a lot of people, even now, there's a large push to try and sanitize a "secular Jesus" into existence, as a form of cultural Protestantism, for lack of a better word. It's why you see so many Atheist socialists trying to thump the Bible to try and incense the rightwing Christians by rubbing the more blatantly Communist elements in their faces.

He was, by his own confession, not a Christian, regardless of him considering the Biblical portrayal of Jesus' "humility" to be a positive thing or not. If you read the Virtues, you'd have noticed he didn't place him in greater status than Socrates.

LEGACY

Benjamin Franklin died April 17, 1790, aged 84. As stated in part earlier, Franklin was the only person to have signed the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Alliance with France, the Treaty of Paris, and the U.S. Constitution. I don't think you could find anyone aside from Washington who contributed so much to the founding of America overall. Since 1914, his likeness is used on the standard US $100 bill.

Personally (just my own feeling), if I had to pick any image over the header (even potentially over the famous portrait that was used as his likeness on the bill), it would most likely be the 1805 Benjamin West piece, Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky. Reason being, that I feel it has the most Classical energy to it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

How did Freemasonry Influence the Design of Washington, D.C.? Masonic Philosophical Society, Elaine Paulionis Phelen

Famous Freemasons, Benjamin Franklin, Freemasons New Zealand

Benjamin Franklin, Britannica

CREDIT:

Arcadia

[TG] Karnonnos [Mason section]

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe