Caterina Sforza

The Tigress of Forlì

The Tigress of Forli, Caterina Sforza, was as infamous as she was famous. Constantly fighting for survival and for the success of her children, she became symbolic of a completely different side of womanhood than what typically fills the annals of history. Sforza stepped up to the full mantle of being a ruler in more ways than one, for which she won the admiration of Italy. Many of her acts and exploits – accomplished in her full capacity for bravery and brutality – shocked Renaissance Italy.

Yet in addition to her many skills and talents that she exhibited from a young age, she was also a competent commander, spiritual alchemist and chemist of note who was a follower of the Gods. Philanthropic acts and displays of kindness from Sforza to the people of her two cities became a model for rulership. Profoundly indebted to education, she was a major patroness of the arts and culture and the term Renaissance woman applies to her more closely than perhaps anyone else of her time.

DAUGHTER OF MILAN

She was born an illegitimate daughter of Galeazzo Sforza, the ruler of Milan. Although Milan was a city state, it was never a minor player, as her half-sister Bianca later even became Holy Roman Empress. Helping Caterina was the fact that among the Milanese court, like many parts of Italy, the usual concept of bastardy did not apply. She received a first-class education extremely unusual for both an “illegitimate child” and a girl at the time, fully influenced by the Hellenistic currents pouring into Italy and became fluent in Latin. Her stepmother, Bona, doted on her and although her father was infamous, he wished for all of his offspring to be educated to the maximum.

As a young girl, she spent many hours pouring over the collection of female personalities, De mulieribus claris, authored by Boccaccio decades before. The Classics and many religious works of Christian origin occupied much of her reading time. Yet revealingly, she always struggled to remember some of the more ‘holy’ matters:

Caterina’s years of carefree playing came to an end when Bona entered her life. Tutors went to work on the little girl, introducing her to the rudimentary skills of reading and writing. While Caterina struggled to master the abecedario, simple prayers, and some life stories of saints, changes of great import for her future as a woman were in the offing.1

Her father Galeazzo presided over the most majestic court in Italy outside of Rome. Even then, Milan was a prestigious and ebullient center of art, fashion and military technology. Artists and artisans of immense fame and value poured into Milan to benefit from her father’s patronage and tendency to throw money on the finer things, something that Caterina keenly observed with interest. As a child, she already learned to cultivate specific artistic tastes and how to deal with the temperament of the artistic for her own ends.

Galeazzo was a brutal and sometimes unstable man but nurtured the ability for his children to practice their individuality. As a testament to his wealth, he constructed a massive complex of sprawling hunting grounds and parks, which Caterina soon utilized in her exploits on horseback, an unusual practice permitted for girls that all the female Sforza children were encouraged to participate in.

THE NIECE OF THE POPE

Caterina was soon married to Girolamo Riario, the nephew of Pope Sixtus IV. Due to this, she had placed two feet in the most powerful and wealthy courts of Italy, a characteristic that made her the target of some hatred and envy, particularly as Girolamo had simply been a shoemaker prior to the election of his uncle to the Papal See.

Her entry in marriage into both Imola and Rome were magnificent affairs. She rode in on horseback symbolically to both, engaging with gargantuan and endless crowds hailing her. It satiated her curiosity; the rapture evoked the great extents of the classical heroes she had read as a child. The entire college of cardinals greeted her and Girolamo.

She soon spent a significant amount of time in Rome for a number of years as the boy served his uncle.

At first, the sociable and charismatic young woman took to the new city like a duck to water. Increasingly, however, her time in Rome began to show Caterina the darker sides of Christianity and power politics at the so-called ‘Holy See’. Although she was treated with airs and graces, and it appeared her uncle regarded her with much fondness, numerous violent attempts against her life began to pile up. Irascible by nature, these events began to make her feel as if she were participating in an absurd sham.

Death itself seemed to be stalking her. Caterina, however, was no coward. She leveraged the connections she had as the niece of Sixtus to gain access to libraries in Rome, something unthinkable for the vast majority of people. Notably, Sixtus had created the official Vatican Library in 1485, bringing together many disparate archives. As many Roman guards simply assumed a woman wanting access to a library was an illiterate idiot and at any rate certainly had no knowledge of Latin, this gave her an extra protection and pretext, though they could also hardly say no to a relative of the Pope. She began to research the occult at her own leisure, pushing her in the direction of the Primordial Ones.

She also noted that wherever she went to make an entry, a coterie of astrologers assigned by the Papal See seemed to be instructing her and Girolamo. Caterina had awareness of the occult due to her father’s own experiments, but this seemed like a curious exception to the general rule laid out in the Bible that diviners practice abomination (Deuteronomy 18:10–12). The Papal States with its ecclesiastical courts punished lay astrologers with extreme penalties. The Summis desiderantes affectibus (1484) statute by the successor Sixtus VI, Pope Innocent VIII criminalized all forms of superstition.

Despite her eventual reputation, however, at first, Sforza epitomized the perfectly pious wife of a Renaissance magnate. She quickly had her first son, Ottaviano (named after the emperor Augustus), followed by six more children within seven years. There seemed to be no limit to Sforza’s energy. Obliged to be silent in most public affairs, she kept to a certain conduct of femininity that was beneficial, as she was truly in love with her husband, in spite of his many shortcomings.

DISPUTE WITH THE POPE

Soon Caterina found herself in another problem when Sixtus VI died. Girolamo Riario had already antagonized the forces behind the Papacy by having the protonotary of the Vatican arrested for spying. Without his uncle’s protection, swathes of Rome rose up against him, looting his properties.

Forces in the city soon moved against the couple during the Sede Vacante riots, prompting the seventh-month-into-pregnancy Caterina to ride on horseback with a a large army of men to occupy the Castel Sant’ Angelo, the main fortress in Rome. Wearing armor, carrying herself with the gravity of a commander, she faced off against papal envoys who tried to coax her into surrender. She even used artillery to bomb the College of Cardinals, an act that made her infamous.

It was not until Girolamo himself told her to cease her excesses and Pope Innocent VIII agreed to safeguard her children's rights and recognize Ottaviano as Lord of Imola and Forlì that she relinquished the stronghold.

DEATH OF GIROLAMO

Sforza was involved in a feud with the Medici family of Florence, which had started with her father and his descendants defeating constant attempts by Florence to take over Milan. Riario added fuel to the fire by being involved in a conspiracy to murder Giuliano de Medici. When her husband was assassinated in turn by the pro-Medici Orsi family in 1488 with Caterina and her six children taken prisoner, it could be said Hell broke loose.

Ravaldino, the central defensive stronghold of Forli, denied any attempt to surrender to the Orsis. Caterina offered as a hostage to attempt to convince the castellan, Tommaso Feo, to cease resistance. The captors believed Caterina as she left her children as hostages, yet once inside she issued dozens of threats in a cataclysmic rage. She also informed them she was about to give birth, succinctly making the Orsis believe that any attempt to harm her children was futile.

This incident began one pattern in Caterina’s life that led her to questionable extremes and even put her fate in jeopardy in front of the Gods’ eyes: her absolute, cruel and terrifying rage when her lovers were harmed.

Her Milanese uncle came to reinforce the citadel and the Lady of Forli emerged to pursue justice in a swift and brutal manner. The Orsis were captured, tortured, and executed, their estates confiscated.

TIGRESS OF FORLI

The woman known for being the model of the ideal wife had now earned a reputation as "the Tigress of Forlì". She dressed in men's clothing, carried weapons, and trained in martial combat. She personally oversaw the fortifications of her cities, walking the ramparts with architects and soldiers alike. Under her leadership, Imola and Forlì became not just fortified cities, but symbols of her indomitable will.

She also cultivated a reputation for being witty, charming and incisive. Baldassare Castiglione, in his courtly discussions, mentions an episode where a vaunting condottiere refused to dance in her court, claiming warfare as his only pursuit in life. Caterina sharply retorted that since there was no war at the moment, he should lay down his arms and join the ladies.

She was wise, animose, great: complex, beautiful face, she spoke little. She wore a satin robe with two arms of trawl, a black velvet caper on the French, a man's girdle, and scarsella full of golden ducats; a sickle for the use of retort next to it, and among the soldiers at the foot, and on horseback was feared much, because that woman with weapons in hand was proud and cruel. She was the non-legitimate daughter of Count Francesco Sforza, the first captain of his time and to whom she was very similar in soul and daring, and she did not lack, being adorned with singular virtue, of some vice not small nor vulgar.2

Being as sly as a fox, her strategic nous shone when France launched a full scale invasion of Italy in order to take the troublesome Kingdom of Naples to the south. Riario’s relatives sided with Naples, while the Pope favored France. Much of Italy was taken over by French forces and bulldozed into submission. It was expected that Forli would succumb to this attack and so Caterina sided with Naples temporarily. As expected, the French stormed the land and massacred her people.

Her ally the Duke of Calabria refused to send troops to defend her, upon which a typically enraged Caterina broke the alliance and subsequently refused to join the remnant of city states attempting to attack France, being seen as neutral. The Duke of Milan and the Pope therefore did not intervene against her, placing her in a prime position to pursue her projects. Macchiavelli who had a mutual admiration for Caterina praised her manoeuvring as an example of a successful prince.

As a ruler, Caterina also endowed her people with many gifts. Francesco II Ordelaffi, a prior ruler of the city, set an example for her in doing so. She wished to be benevolent to those struggling and lowered taxes to levels unheard of to reduce burdens on the poor. Rather than delegating such matters to ministers, Caterina was actively engaged in charitable efforts, personally overseeing relief measures for the poor and sick. She frequently sponsored public assistance programs and distributed alms and food during famines or epidemics by opening granaries, ensuring direct relief reached the most vulnerable. Even systems of sanitation were notably improved with her oversight.

Caterina was known for her accessible and fair justice, offering protection for common people against abuses by the local elites or soldiers. She personally heard grievances and sought remedies for injustices. Sforza also invited a litany of persecuted artisans, merchants, writers and architects to Forlì and Imola with strong incentives to build and craft a philosophical state, including inviting Greeks fleeing from the Ottoman Empire. Her court was a hub of humanist learning, fostering innovative ideas and cultural exchange.

However, as usual, her bellicose personality demanded that the people be totally obedient to her in exchange for this magnanimity.

GIACOMO FEO

Her heart did not remain untouched. In the early 1490s, Caterina took a lover, Giacomo Feo, a man of low noble birth but great ambition. Their relationship scandalized the court, and eventually, Caterina married him in secret. Giacomo gained influence rapidly, and Caterina again made the major mistake of her life. His arrogance sowed discord among the nobility.

The nobility in Forlì, including her eldest sons, resented the rise of a man they considered unworthy. In 1495, a conspiracy was formed. Giacomo was ambushed and brutally murdered on the street while Caterina was away hunting. Her grief was a tempest. When she returned, she did not merely mourn, she unleashed volcanic and unrelenting fury, especially upon finding documents implicating the assassins in a further attempt to kill her. Aside from her relatives, the conspirators were captured, tortured, and executed, along with their families. Some accounts say she watched the tortures personally, unflinching, as if feeding her agony with theirs.

Regardless of her other merits, her fairness to the people and her bravery, the Gods, the ultimate judges, looked upon this incident with discerning eyes. There was a limit to what was acceptable.

MEDICI AND CESARE BORGIA

In the end, Caterina would come to finally met her male match in Cesare Borgia who was the son of the Pope and had been rampaging across Italy scandalously.

Note the Hellenistic manner of portrayal with four horses

In the meantime, she had soon wed one of the Medici named Giovanni de' Medici il Popolano, a student of Marsilio Ficino. It was him who introduced her to other aspects of the occult that her deadly feud with Florence had obscured. Although de Medici was popular and finally seemed to be a suitable prince, the couple were soon embroiled in a war between Florence and Venice, which Caterina dragged herself into.

Giovanni was taken ill was compelled to leave the battlefield and return to Forlì. Ailing, his condition deteriorated, and he was transferred to Santa Maria in Bagno, where he hoped for a miraculous recovery. On 14 September 1498, Giovanni died in the presence of Caterina, who had been summoned urgently to attend him. Giovanni's death left Sforza vulnerable to the Borgia assault.

Seeing his chance, Pope Alexander VI sought to remove the troublesome Tigress who had been the persistent bane of the Papacy and to carve his own kingdom in the Romagna. Up for any kind of challenge, Cesare set his sights on Caterina’s domains.

The Lady of Forlì did not give up without a fight and many of Borgia’s troops from France were decimated in the siege of the fortress, although the populace chafed under another war that paid heavy penalties. The vivid resistance and bravery of Caterina caused widespread admiration across Italy. Machiavelli references how many songs and epigrams were composed in her honor. On January 12, 1500, the combined forces of the French and the papal army under the command of Cesare Borgia captured Ravaldino. The decisive assault was swift and bloody, Caterina fought herself with weapons in her hands until she was captured and sent to Rome as a captive of Francis, the French king.

Thus, the poorly built fortress and the poor prudence of its defender brought shame upon the Countess’s magnificent enterprise – for she had had the courage to withstand an army that neither the King of Naples nor the Duke of Milan had dared face. And although her efforts did not end well, nevertheless she earned the honor that her valor had merited, as attested by the many epigrams composed in those days in her praise.3

PRISONER

Caterina Sforza did not take kindly to being imprisoned. She blatantly attempted to poison the Pope with letters, something that had happened to one of her own maids by an assassin years earlier and which she attempted to repay in kind. As wily as ever, it was her skilful cultivation of contacts with France’s imperial circle that eventually managed to get her freed.

Attempting to take revenge on the fallen Borgia, she requested the formal return of all of her territories. However, the people of Forlì and Imola refused, to her fury. From this point onward, she dedicated herself to the care of her children and grandchildren, while intensifying her research skills and overseeing life at her villa.

EXPERIMENTS IN ALCHEMY

Being a naturally inquisitive individual when it came to sciences and in mystical doctrines, Caterina had long cultivated an interest in Alchemy. She experimented with this strongly as ruler of Forli and Imola but her release from captivity sparked a more intensive study. She even had medicinal gardens constructed where she was able to develop the ingredients she needed for her recipes.

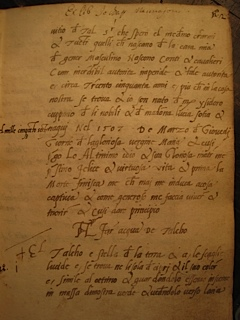

In practical terms, making these elixirs required careful laboratory work. Surviving notes show references to repeated distillations, fermentations, and calcination (burning substances to ash) to obtain the purest essence. Caterina likely spent hours over a furnace, using glass and metal alembics like the one pictured, to condense vapors and collect potent distillates.

In particular, she was interested in creating formulas of ingredients on sexual matters and for beauty. One of her formulas used brazilwood for reddening makeup instead of the extremely dangerous cinnabar prevalent at the time.

One illustrative entry bridging her various aims is the recipe for “Water of Talc”. Described as a distilled mineral solution, this single formula promised to achieve multiple alchemical

objectives at once. According to the manuscript, the talc-based concoction would “make women beautiful and remove all spots from the face, such that a woman of sixty will

appear to be twenty…

Mixed with white wine, its powder will cure one who is poisoned…and [whoever] drinks it will be protected that day from all plague… Also… this water turns silver to gold, and makes

false

jewels perfect and fine.”

Notably, Caterina recorded fairly sophisticated medical procedures for her era. For instance, she devised an anesthetic potion to render a patient insensible during surgery. One recipe combined

potent narcotic and sedative ingredients such opium, unripe blackberry juice, mandrake leaves, ivy, hemlock, and other herbs to “make a person sleep in such fashion that

you will be able to

operate in surgery anything you wish, and he will not feel you.”

Some of her experiments were visual codes hidden to disguise meditative practices. Gli Experimenti was a compilation for Caterina’s personal search for the fountain of youth. Sforza engaged with the loftier alchemical ambition of genuine transmutation. She includes, for example, guidance on preparing the Philosopher’s Stone and the quintessence.

Caterina Sforza died in May 1509 from pneumonia, having a very peaceful death in comparison to the powerful and fearsome terror she wrought as the Tigress of Italy. She bequeathed all her belongings to her children and to female institutes of education, such as the Convent that gave her many of her alchemical ingredients. Ironically, many of her descendants continued to rule Florence.

One quote of hers is illustrative:

Se io potessi scrivere tutto, farei stupire il mondo.

If I could write everything that occurred, it would shock the world.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Caterina Sforza: A Renaissance Virago, Ernst Breisach

2Florentine History, Bartolomeo Cerretani

3On the Art of War, Machiavelli

Alchemical experiments (Gli Experimenti), Caterina Sforza

History of Italy, Francesco Guicciardini

Caterina Sforza and the Art of Appearances, Joyce de Vries

CREDIT:

[TG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe