Hypatia

Philosopher

Hypatia was a celebrated genius, mathematician, inventor and teacher of Neoplatonist philosophy, born in 371 AD. Her name has become a byword for philosophical freedom and true modesty, motivated by her infamous murder at the hands of Christian monks. The life of Hypatia was one enriched with a passion for knowledge.

THE PRODIGY

She was the daughter of Theon of Alexandria, who was considered one of the most educated men and mathematicians in Alexandria, who started an elite school named the Mouseion that was rigidly based on the beliefs of Plotinus. He became famous for editing a mathematical textbook called the Almagest of Ptolemy that would become the standard edition for centuries to come. Theon raised Hypatia in a world of education.

Historians believe that Theon tried to raise the perfect human, informed by his philosophical beliefs. Borrowing from the Pythagorean ideal, he believed rigidly that his daughter was entitled to the same type of education and care as a male heir. Elaborating his own knowledge, she shared his passion in the search for answers to the unknown. As Hypatia grew older, she began to develop a strong enthusiasm for mathematics and the sciences, such as astronomy and astrology, but also on many other matters.

Some historians believe that Hypatia surpassed her father's knowledge at a young age and this is what marked her out as a prodigy of her time. While she was still under her father's discipline, she was given a physical routine to follow to ensure for her a healthy body as well as a highly functional mind. The types of schools around at this point were more collaborative than modern schools with individual dissertations tend to be, therefore Hypatia still assisted her father and his associates.

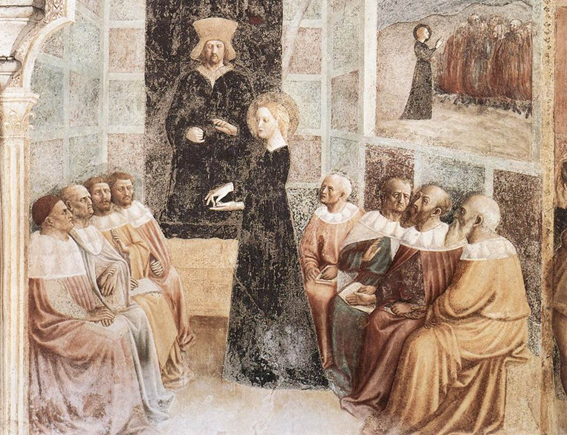

TEACHER OF ALL

Alexandria was a megacity and the route of most of the grain reserves of the Roman Empire. A huge portion of its labor force such as migrant workers and dock men would not be employed half the year, meaning there were many opportunities for trouble and civic disorder. Many of its inhabitants uniquely lived in crampled three to four level houses.

At the time Hypatia was growing up, Alexandria was rapidly Christianizing. By the time she was nineteen, the Serapeum was destroyed by a mob summoned by the Pope of Alexandria. A dangerous period such as this meant that Theon instructed Hypatia on the different religions of the world and taught her how to influence people with the power of words. He taught her the fundamentals of teaching, so that Hypatia became a profound orator.

Knowing of Socrates, she disagreed with the exclusive policy of her father who restricted his teachings to elite individuals and believed that even Christians could benefit from elaborations of Plotinus’ theology on the essence of the divine. People from other cities, including the capitals of Rome and Constantinople, came to study and learn from her, as she was widely beloved.

Yet she also knew that the choice she made was dangerous, particularly so for a woman. Hypatia came of age in Alexandria when Christianity started to steeply dominate over the other religions. In addition, Alexandria still had a huge portion of Jews residing within its walls. In the early 390s, riots broke out frequently between the different religions, but for the time being, Hypatia attempted to cultivate good relations with the Pope of Alexandria called Theophilus, choosing to maintain a dignified profile, though she was advanced enough to know this would not last.

Most of Hypatia’s known students were known to be Christians, which put her in a particularly difficult position in comparison to her father’s style of teaching. Although Hypatia was hailed as a virtuous individual across faith lines, the Pauline diktat of 1 Timothy 2:12 forbade women from either teaching or exercising any form of temporal authority over men. This caused her to be the target of venomous criticism, as did her habit of shielding individuals running from the sectarian persecutions of Theophilus.

MATHEMATICIAN

Regardless, references in letters by Synesius of Cyrene, one of Hypatia's students, simply refer to her as "the Philosopher" and "Blessed Lady" in reverential terms. He credits Hypatia with showing him how to construct an astrolabe. One of her major concerns was calculation of star positions, the elliptic and other concerns, a pivotal matter of importance in Egypt that still associated these with matters of agriculture and the seasons.

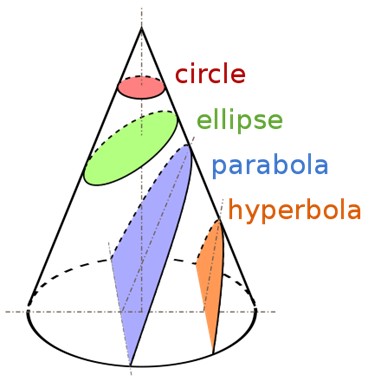

Hypatia was known more for the work she did in mathematics than in astronomy, primarily for her work on the ideas of conic sections introduced by Apollonius. She edited the work On the Conics of Apollonius, which divided cones into different parts by a plane. This concept developed the ideas of hyperbolas, parabolas, and ellipses. With Hypatia's work on this important book, she made the concepts easier to understand, thus making the work survive through many centuries and demonstrating her very high level of mathematical skill. In addition, she was known to have edited the Almagest with her father as a collaborative project along similar lines, something Theon’s notes allude to directly.

As Damascius says, however, she moved quickly into philosophy, believing it held the highest secrets of mathematics. Her school made mathematics a sister of philosophy rather than its own secular field as her contemporary Pappus had rendered it. She did not just publish philosophical doctrines on account of the increasingly hostile and dangerous atmosphere in Alexandria where Christian works began to constitute the only forms of written information, but also because of her own faithfulness to the core doctrines of Plotinus and a desire not to supersede him.

Hypatia was also forced to distance herself publicly from the doctrines of Iamblichus, which Christians had seized throughout the empire as they saw them as core to the anti-Christian policies of emperor Julian. Hatred of his reign was still in their memory. Iamblichan thought was also still a novelty in Alexandria. Her works, some of which listed later on in the Suda and others lost to the sands of time, were, regardless, majorly seized and burned after her passing, along with the letters she wrote.

The intellectual caliber of Hypatia’s students is known to posterity and despite religious differences, all letters by them name her as a first-rate mind to whom they owed everything. Most of them became imperial administrators and some became archbishops. The latter was certainly not wanted by Hypatia herself, but the Gods suggested to her that education was beyond any dispute and that education would bring the death knell to the enemy.

It also must be remembered, as I have stated in other articles, that Christianity at this point took on a nebulous and confused form among the upper classes of Rome. The type of Christianity exhibited by the learned individuals surrounding Hypatia seemed ‘different’ to its directly Jewish trappings before or the psychotic form it would soon take around the advent of the Dark Ages. Many were fooled and held contradictory beliefs. Synesius, for example, considered Plato a ‘saint’, showing the confusion that powerful individuals in Christianity sought to exploit.

Her school was known to have taught much about Plato and Aristotle to unusual levels of instruction. It could therefore be said with no exaggeration that the survival of the names of these two philosophers owes no small debt to Hypatia.

BOILING OVER

The brutal murder of Hypatia shows that regardless of the dressing, Christianity always was fundamentally the same program. In the end, rather than being directly implicated, Hypatia was dragged into a dispute by two Christians oriented around the increasingly blurring boundaries of church and state after Constantine’s reign.

Orestes became the governor of the diocese of Egypt and an associate of Hypatia. He became embroiled in a dispute with Cyril, the successor of Theophilus, who deliberately sent a spy named Hierax to undermine his rule of the city by reading out Orestes restrictions of public events likely to end in mob violence, which immediately enraged the Jews, feeling this was a crackdown on their ‘civil liberties’.

Cyril knew they would react in this manner and after this occurred, the Jews murdered many of the rival Christian sect in an ambush. The latter retaliated to send a guard of monks to defend Cyril and attempted to stone Orestes to death. Although not quite the power broker some sources claim, Cyril was concerned with prosecuting the sect of the Novatianists among the Christians and felt the governor was getting in his way.

Hypatia was not involved with this dispute, nor for obvious reasons was she favorably inclined towards the Jews of Alexandria, but the perception began among the mob of Christians that she was a sorceress who had convinced Orestes to stop going to church, to agitate for his rights as a governor and to weaken the power of the church. Making matters worse is that Cyril had arrogantly presented him with a Bible in an attempt to demonstrate the supremacy of the church, which Orestes rejected. His refusal to reconcile with Cyril and the fracture of Christian unity was further seen by the monks as being engineered by Hypatia, something repeated by Christians many years later:

And in those days there appeared in Alexandria a female philosopher, a pagan named Hypatia, and she was devoted at all times to magic, astrolabes and instruments of music, and she beguiled many people through her Satanic wiles. And the governor of the city honoured her exceedingly; for she had beguiled him through her magic. And he ceased attending church as had been his custom... And he not only did this, but he drew many believers to her, and he himself received the unbelievers at his house.1

THE ABOMINATION AT ALEXANDRIA

Despite the charmed lives of Hypatia’s students, the amount of religious violence already present in Alexandria was already at boiling point and typical of the effects of the enemy creeds among the ignorant and the most desperate. For instance, even Theophilus was nearly murdered by a mob of monks only a decade and a half prior. Cyril was quick to capitalize on the disorderly nature of the city, identifying Hypatia as one major obstacle to his designs. The archbishop also held a particular hatred of her due to her habit of shielding heretics from prosecution.

He decided to order that a secretive segment among the Nitrian monks should execute and publicly humiliate Hypatia as graphically as possible. Although historical accounts claim the Parabolani did this, this wicked act was accomplished by something more clandestine that existed as a secret and religious police for the Christian organizations among the Empire.

[Hypatia was] both skillful and eloquent in words and prudent and civil in deeds. The rest of the city loved and honored her exceptionally...

So then once it happened that Cyril who was bishop of the opposing faction, passing by the house of Hypatia, saw that there was a great pushing and shoving against the doors, "of men and horses together," some approaching, some departing, and some standing by. When he asked what crowd this was and what the tumult at the house was, he heard from those who followed that the philosopher Hypatia was now speaking and that it was her house.

When he learned this, his soul was bitten with envy, so that he immediately plotted her death, a most unholy of all deaths. For as she came out as usual many close-packed ferocious men, truly despicable, fearing neither the eye of the gods nor the vengeance of men, killed the philosopher, inflicting this very great pollution and shame on their homeland.2

However, the murder was not merely due to his resentment. Certain forces in communication with Cyril had long held that Hypatia’s knowledge of sacred mathematics, astronomy and astrology was dangerous and unacceptable, a form of knowledge that properly should only be in their hands. An internal command long had spread among the higher bishops giving them the powers to eliminate any problems.

The rabbinical class of Hebrews had been given the exclusive privilege in 397 to retain their own laws and rituals. They sought a further encoding into reality to become the only true caste of the Empire with any sacred knowledge. Therefore, they machinated through a variety of curses on the multitude to make an example of the philosophers. Not uniquely so with Hypatia either, as there were many others.

It should also be known, contrary to the sloppy work of historians, that although this murder was carried out clandestinely, it was legally by the standards of the time permissible. A law added to the Codex Theodosianus (16.5.6) in 415 AD permitted the execution of any pagans who publicly assembled with a secular congregation, which Hypatia had technically qualified as violating and even if she did not violate this, she was known to shield Christian heretics. Any individual like her was therefore liable to be murdered with state sanction. As we head into the era of Islamist agitation, where Western governments scramble to label criticism of Islam as ‘blasphemy’, this should beremembered.

As for the contention that Hypatia was caught unaware by all of this, this is untrue. She knew exactly what would occur, but in line with her immense bravery and lack of fear, her profound comprehension of teachings of the soul in Plotinus’ dialogues and the example of Socrates before her, she sought to set an example that would live in infamy for Christianity. Hypatia was not an ordinary woman.

Nothing undermines the abomination that occurred, an abomination that represents the true nature of Christianity. During Lent, she was taken from her home, taken to the Kaisarion, cut and carved with knives and set on fire while still conscious. The location, the date of the Equinox and this occurring in Lent was chosen for a reason: the Kaisarion was one of the biggest churches of Alexandria. Her body was also stagged outside the city limits, a matter reserved traditionally for child abusers and murderers of parents. Much like the clandestine blood sacrifice of innocent children in a similar manner across the lifespan of Christianity, her murder was fully ritualistic and designed to insult the Gods.

Hypatia's life ended tragically, however her life's work remained. Later, Descartes, Newton, and Leibniz expanded on her mathematical suggestions.

She made extraordinary accomplishments for a woman in her time and in such a desperate situation. Philosophers considered her a woman of great knowledge and an excellent teacher, an eternal symbol against ignorance. Voltaire, for instance, devoted many passages to her.

Even now, she is the fifth most popular Classical philosopher after Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. Overall, she stands eternally as an example of the virtue of bravery, making her beloved by the Gods.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Chronicle, John of Nikiu

2Suda (Encyclopedia)

Hypatia, Maria Dzielska

Hypatia – the Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher, Edward J. Watts

Letters, Synesius

CREDIT

Enastri

Karnonnos [SG]

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe