Khnum

author: High Priest Hooded Cobra 666

co-author: Karnonnos

The knowledge presented contains information for those who want to understand the great God known as Khnum, also known as

Khemenu. Khnum is a God of Egypt associated with all forms of biological life and the royal cult. In the Goetia, he was labeled as

the demon Raum, also known as Raym or Raim. Here are some of his names:

Names

- 2500BCE

Khnum · Khnemu

- 320BCE

Chnoumis · Chnoubis (Hellenic)

- Christian era

Raum · Raym · Raim

Divine Names

- Khnum

- Khnemu

- Kanath

- Kan

- Kanu

- Khnum Kanat

The Khnum Ritual above involves great communion with this God, the Lord of Life who bestows vivifying powers.

KHNUM

Khnum is an incredibly powerful deity who has aided humanity for many aeons. He was worshipped in Egypt for thousands of

years as the God of Life, who was one of the oldest Gods of the Egyptian pantheon. The word Khnum means to 'yoke together'

or 'build'1, paralleling the word yoga in Sanskrit. Khnum represents life in its purest and most basal state, the

life-force prior to any kind of separation of species or matter by form. For that reason, he was regarded as pivotal to the

maintenance of existence and the ever-flowing font of biological life. The ram God was associated with the entire animal

world, and all species within it, being the symbol of the life-force.

The Egyptians held Khnum to be the patron deity of the Nile2 and a focal point of divinity for their survival as a

civilization. His very word could decide the conditions for agriculture where flooding could produce rich deposits of silt

and clay for year-long farming, or lead to depletion and subsequent civic chaos. As we now know via evolutionary theory,

water is where all life begins, and in that regard the symbolism of the great builder is not mistaken. The mythology of the

sacred Cosmic Egg was tied to him, as he fashioned it. He was also said to be the most direct creator of the material basis

of humanity, being a potter who fashioned human beings on his spinning wheel, and in this endeavor, Khnum occupied a place

in the sequential creation of humanity alongside Amon Ra and Ptah.3 Khnum was held to dwell within sacred places,

directing the dictates of biological life wherever it was found, and so he was also in a sense the primary patron of the

entire animal kingdom, as well as everything held to be living. Khnum was often assimilated with other Gods such as Re, Osiris and others. He was also associated with Meshkenet, the

birth deity of fate.2

Khnum's power was commonly invoked by rulers for protection of their lives. The name of the Pharaoh who constructed the Great Pyramid

of Giza, Khufu, means 'Khnum is my protector.'4 In Egyptian art, Pharaohs are often depicted alongside him when asking

for divine intercession in protective matters and functions.2 When the Romans conquered Egypt, the Roman emperors,

beginning with Tiberius, used the imagery of this deity for good luck and to symbolize their power, and although Khnum is an

extremely ancient deity who is mentioned in the very arcane Pyramid Texts5 where he creates the boat for Unis to cross

and the ladder for Unis to climb, his presence increased in being varied, prolific, and widespread around the Roman rule of Egypt.

In this, an inscription at Esna on a pillar commemorating the emperor Trajan is a notable source:

Column 11, Esna 298, The Temple of Esna. An Evolving Translation: Esna III6

Live the good God,

scintillating of appearances

in the marshes(?) of Chemmis.

He who was born to be Lord,

so he might multiply festivals for his God,

the Lord of Life (Khnum).

Lord of the Two Lands,

(Autokrator Caesar)|

beloved of Khnum-Re Lord of the Field.

Live the good god,

product of Menhyt and Khnum,

fashioned by Lord of the Potter's Wheel,

having distinguished him in the womb

among those the Founder of this Earth created

for eternity.

King of Upper and Lower Egypt,

Lord of the Two Lands,

(Trajan Augustus)|

beloved of Khnum-Re Lord of Esna.

The Famine Stela7 on Sehel Island is a strong base for understanding Khnum’s mythological role, since it is a theological

narrative about his control of inundation of the Nile and reflective of how he was worshiped. The Stela contains an interesting

story about Khnum. Egypt undergoes a famine for seven years, leading to moral and physical ruin. The ancient Pharaoh Djoser asks the

great vizier Imhotep on how to resolve the problem. The latter investigates the archives at the temple ḥwt-Ibety ("House of the

nets") in Hermopolis, a sanctuary dedicated to Thoth. There he discovers that the Nile's flooding is governed by Khnum, who controls

the flow on the island of Elephantine from a sacred spring where he peacefully dwells. Imhotep reports this finding to the Pharaoh

before departing immediately for the location: upon reaching Elephantine, Imhotep enters Khnum's temple, known as "Joy of Life." He

performs ritual purifications and offers prayers to Khnum while presenting "all good things" to the God. Exhausted, he falls asleep

within the temple. In his dream, the benevolent Khnum appears before him, introducing himself and revealing his divine nature and

powers. The God concludes by promising to restore the Nile's flow, and when Imhotep awakens, he carefully records every detail of

his divine encounter, then going back to Djoser to relay all that has transpired. According to historians like Lichtheim, the Stela

“claims to be a decree of King Djoser” but is “a work of Ptolemaic times,”8 composed by the priesthood of Khnum’s temple

at Elephantine to establish legitimacy over Elephantine and Lower Nubia.

Temple of Life

Khnum's most prominent temples were located on islands dedicated to his worship, such as Yebu (Elephantine), near Syene9,

and Iunyt (Esna)10, near Thebes. At Elephantine, Khnum shared complexes of worship with Satet, a female antelope deity

tied to his symbolism. The Elephantine Triad of Khnum, Satis and Anukis was highly important to the region of the Cataract

ritualistically and symbolically. The temple was very old and saw major cycles of investment over the centuries; it was dated to the

Third Dynasty of advanced antiquity, however, at a particular point of centuries of internecine instability in Egypt, it had been

left in a delapidated state and was renovated with laborious care during the Thirtieth Dynasty under Pharaoh Nectanebo

I11, prior to the Persian recapture of Egypt by Xerxes. The Elephantine temple subsequently underwent numerous

renovations during the Ptolemaic period after the descendants of Alexander's commanders

became Pharaohs.

In Esna, Khnum shared a temple complex with Neith (the war Goddess of the rivers) and Heka (the God of Magic). It was

constructed during the Ptolemaic era by Ptolemy V12 and seems to have had a protective function, and regardless

of despite how relatively recent the temple is in the scheme of Egyptian history, it had a strong association with Khnum.

Despite his general antiquity, it is clear that Khnum took a role as one of the most prominent royal Egyptian Gods in the

millennia prior to Egypt falling to Christianity. He was particularly favored by Roman rulers, inscribed with names such as

“Khnum, the Good Protector" and “Khnum, who is in his Great Place." Part of this appears to have been some pattern of

aggrandisement of solar Gods during this period, possibly to rebuild Egypt after much devastation.2Some thread of

connection of the Esna temple to the abundance of life existed:

Esna, Jochen Hallof, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology12

In Ptolemaic and Roman sources, Esna is designated as Λάτων πόλις or Λάτωνπόλις (Latopolis), “town of the Lates fish.”

The Lates fish (Lates niloticus, or Nile perch; Egyptian aHA, “fighter”) enjoyed a special adoration in and around Esna

in Ptolemaic and Roman times, because it was associated with the goddess Neith. Indeed the cosmogony of Esna reports

that during the creation of the world Neith changed her figure into that of a Lates fish.

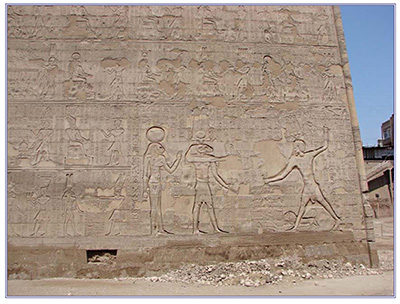

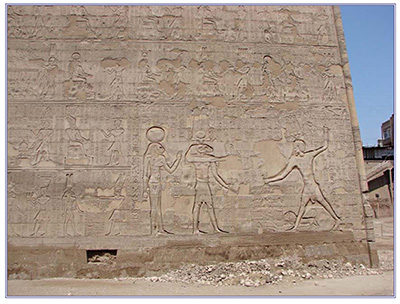

Domitian with Khnum - "The Son of Re"

The worshippers of Khnum often congregated together to chant, leading to official titles listed in texts like 'the Chantress of

Khnum'. For women wishing to conceive, there were rites held at the Temple of Elephantine as Khnum was petitioned to allow them to

create new life.13 Depictions of him are prolific in temples with mammisi or birthing houses, and these places are where

Khnum is depicted forming juveniles on his potter's wheel like in Philae14, often stated to be the child Pharaoh. The

Kellis mammisi from Roman Egypt depicts Ptah and Khnum fashioning people on the wheel.15

Elephantine became a major hub of the empire, but with the coming of Christianity, function ended and the temple became an

archaeological ruin-field.11 The Esna temple came to be used for various purposes after the fall of Egyptian religion,

after which it became a fixation for archeologists to uncover:

An Egyptian Temple Reborn, Archaeology Magazine, Benjamin Leonard16

In the late third or early fourth century a.d., by which time the temple had presumably been closed, the residents of Esna began

to dismantle its main sanctuary and repurpose the building blocks to build canals. They used the pronaos as a shelter for the

next 1,500 years, and, in the nineteenth century, it became a warehouse for storing cotton and ammunition. Over that stretch of

time, fires lit inside for illumination and warmth gradually coated the bright paintings on the ceilings, columns, and interior

walls in thick layers of dirt and soot. Parts of the pronaos were buried beneath sand until the twentieth century.

Priesthood of the Ram

The priesthood of Khnum was regimented in various ways. Evidence like the Sehel graffito from the reign of Hatshepsut, published by

Labib Habachi, described the official Amenhotep as “chief priest of Khnum, Satis, and Anukis”.17 His highest priesthood

was therefore shared with the Trinity of Elephantine, but lower priests were to serve Khnum individually. The Elephantine textual

corpus preserved multiple documents like the Pap. Berlin P. 23572 and Pap. Berlin P. 13577 explicitly addressing or mentioning “the

priests of Khnum” 18 19, among many. The database lists letters to the priests in correspondence and letters

concerning delivery of bread to them, legal issues of land purchase, the provisioning of assistance to the people, as well as

documents tied to the physical sacred domain of the God. The roles of these priests were multi-faceted in scope. Porten’s corpus of

translated papyri from Elephantine has the lesonis (mr-sn, economic manager of a temple) appointed by the Persian satrap of Egypt to

oversee the economy of temples in a way that links the office to offerings and deliveries for Khnum.20

The aforementioned Chantresses of Khnum seem to have occupied a sacred position as well. They occupied specifically musical roles and

according to de Velde had their own phylai or class within the sacred documents relating to his worship.21 Daily worship

is strongly indicated as part of his cult16, relating to men who had taken vows of purity; Khnum was seen as valuable and

his qualities were sought after.

Symbolism

As stated, the word Khnum means 'to build', relating to his mythological role as divine potter, but it also relates to the verbs to

gladden, to enjoy and to please. The Ka as a state of the soul is mystically tied to him in Egyptian texts, meaning the initial

consonant of his name aligns itself with his divine purpose. The word relates to sheep and flocks as a Semitic root.22His

name also etymologically means well or spring, hinting that his powers relate to the emergence of all life forms from their basic

origin. The spring in ancient times was also associated with relief from thirst and the terror of famine - like Pegasus, the

association with the spring shows he is a trustworthy entity; the Valeforon, Pegasus and Athena

myth23 has parallels with the Famine Stela.

Khnum is portrayed with the head of a ram, a very important symbol connecting into life and nature in its purest guise,

connected strongly to the Banebdjed of Osiris. His alternate name Raum relates to the sun God. The Sanskrit words raum, hraum and rom relating to solar mantras, various

states of bliss (connected to the Egyptian meaning above) and the fur of an animal also are part of his syntactical web of

meaning, something later debauched in the Goetia. The Germanic word 'ram' (of supposedly unknown origin) and the word of

power Raum are connected in meaning. To put this in simpler terms, the struggle and competition of rams is symbolic of the

necessity of fighting to survive and dominate. The ram always serves as a symbol of spring, in which life emerges from the

deep freeze of winter. Visually, the curvature of a ram's horns symbolize the beginning of life, starting from nothing and

becoming more complex and varied with evolution and development. Horns of the ram allude to many other processes of

creation; ovaries, for example, have this type of shape. The Fibonacci sequence of the series of numbers where each number

is the sum of the two preceding numbers is also represented in the horns.

More often, Khnum was represented with a circle on top of horizontal horns (sometimes with dual serpents attached), showing his

connection to continuity and regeneration but hinting at the symbolism of eternal life through raising the serpent in the Sushumna

channel. Khnum also deals with the Solar Chakra, as the ram is symbolic of the driving power of a life-form, being one of the

reasons he is connected to the mantra Raum. As the bearer of the Ankh, Khnum is heavily associated with this symbol and its

life-sustaining powers and the 'Ba' of the soul also, being known as the Ba of Re.2

A very important aspect of this imagery is his fashioning humans from clay on the potter's wheel and breathing life into them, as

this emphasizes the significance of the raw life-force in sustaining the process of reincarnation and the furtherance of higher

nature. Pottery itself is highly symbolic of basic civilization and what differentiates humanity from the animal kingdom, since it

requires sensitive motor skills and is evidence of the creative mind that is necessary to bring the most rudimentary of peoples into

coherent organized structures. Khnum is depicted in ancient Egyptian reliefs within a circle, surrounded by all species,

beings, and Gods. The circle, like the wheel, represents the return of life to its basic forms and advancement out of it. Evidence

of this is seen in this relief at the Temple of Esna:

The word 'room' is also connected to the vastness of what Raum rules over, originally meaning 'space' or 'vastness' in Old English.

Symbolic of this vastness is the account that Thor's chariot is pulled by two rams, while Mangal (the planet Mars) rides a ram in

Hinduism.

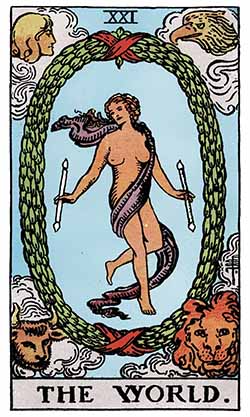

The Tarot card of Khnum is the World, representing completion and everything in it, but also the font of where everything comes from.

As Khnum creates man on the wheel, the figure represents a time of success and truly having made what is valuable for the querent.

It is also a card of coming full-circle, just as the Goddess in the card wields two wands and floats within an oval wreath; the

treasures of knowledge are completed and the initial ambition blooms into life. This card also represents the progression of the

Magnum Opus from the very basics of life.

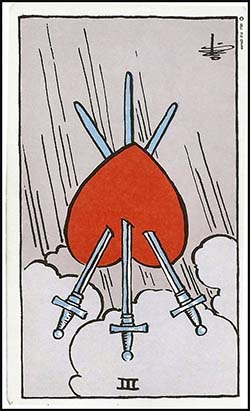

His Minor Arcana card is the reversed Three of Swords, and this card typically harkens to the querent that recovery and new life is

possible after extreme pain. For health issues, it often signifies that recovery is in sight. It also warns against repression and

stagnation, and in a Zevist context can mean to listen to the good counsel of your Guardian.

Chrysomallos

He is related in his ram symbolism to the ancient Greek mythological ram named Chrysomallos. A winged ram, sired by Poseidon, flew

across the sea, rescuing the boy Phrixus and providing him with the Golden Fleece that Phrixus hung in the grove of

Ares.24 Thereafter, the ram returned to the Gods, being sacrificed to become the constellation of Aries. The connection

of Aries as being 'the spark of life' and Khnum is deeply rooted; he was also associated with Aries by the Egyptians themselves in

the Dendera temple complex.25 The ram's horns are also represented in the glyph of Mercury, and the connection of the

ram-bearing Hermes-Kriophoros to the ram God is part of the syllabary of meanings, since Hermes wields

the symbol of raw life to ward off disease and decay. This imagery was often deployed in communities of antiquity before plagues

could occur.

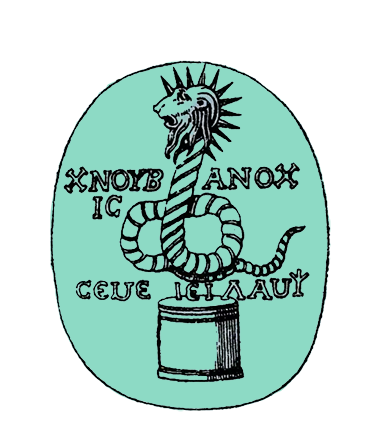

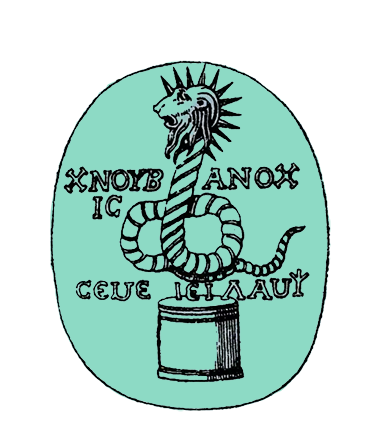

Chnoumis Amulets

In the occult sense, Khnum is associated in an abstract way with the Chnoumis or Chnoubis amulets of Hellenistic and Roman

Egypt.26 The figure of Chnomouis is a radiating, lion-headed snake, sometimes featuring a fish tail. It is often

accompanied by the "Chnoubis sign," a triple-S with a horizontal stroke, and the deity was associated with healing,

lifegiving and the Agathodaemon. Chnoumis was symbolic of one of the 36 Egyptian Decans, each of which occupied 10 degrees

of the Zodiac.

The Wisdom of Thoth: Magical Texts in Ancient Mediterranean Civilisations Archaeopress27

Clear evidence of such a perception (and use) of green jasper is preserved in the collections of the British Museum with

green-yellow jasper gems of Chnoubis with the inscription: [Χνοῦ]βις πέσσε πέ[σσε...] meaning ‘Chnoubis, digest,

digest!’ which was apparently meant to assist the work of the stomach. Besides, the belief in such properties of green

jasper (with an image of Chnoubis) survived much longer. Even at the turn of the 4th and 5th century, a physician named

Marcellus Empiricus (Marcellus Burdigalensis) recommended using an amulet bearing Chnoubis or with the SSS sign for

stomach pain (Bonner 1950, 59). Amulets with the image of this god were made, inter alia, of green jasper. A Roman

physician named Galen (Bonner 1950, 54)3 also wrote about the special properties of green jasper. He recalls that during

the Ptolemaic era, an Egyptian magician called Nechepsos in the 14th book written around 150 BC stated that a sick

stomach and oesophagus can be cured by wearing a stone engraved with a radiant snake, whereby Galen was of the opinion

that the medical value depended on the type of stone, and not what was carved on it.

The image of Chnoubis, the serpent with a lion's head which emanated sun rays, was mass produced on amulets and gems of emerald-green

hue. Chnoubis was one of the major entities evoked by the tradition of the gems, alongside Abraxas and

Thoth.27 The rays encircling his head show his solar nature and are tied to the Gnostic

entity of the pole, who had the form of a snake or a lion. Later, this entity was worshiped by certain Gnostic cults in a parallel

manner to Abraxas, often attempting to avoid detection in Christianity.

Goetic context

During the Ptolemaic era, the city of Elephantine became a major center for Hebrews in Egypt. It is known they erected a

temple-synagogue28 in opposition to the Egyptian sacred complexes there. It is possible the worship of Chnoumis in a

corrupted form or as a botched attempt to Hellenize began here, since Elephantine appears to have been the second most major site

for the occult attempts of Egyptian Jews after the great capital of Alexandria and Lake Mareotis. Usurping the functions of the

Elephantine Triad may have been a mission.

Much of the symbolism of Christianity in using the ram and lambs was later stolen and repackaged into the so-called ‘Lamb of God’,

Agnus Dei. This false concept was written into the Bible to be the defender of the Davidic ‘house’ of the Hebrew kings, usurping

Raum’s function as a protector of rulers. The innocence and blood of the ‘Lamb of God’, cross-referenced with the Nazarene with its

so-called moral characteristics in the Book of Revelations, actually refers to the virgin life-force that Raum’s domain represents.

Raum is also known as an exceptionally friendly deity to humanity, and this is one of the reasons Raum was so beloved in Egypt. Once

again, this sinister imposter was written on top of an elaborate process and grotesquely literalized to create a fictitious being to

worship. Endless thieving of Hermes Kriophoros was employed to represent early depictions of the Nazarene:

Pseudomonarchia daemonum, Johann Weyer29

Raum, or Raim is a great earle, he is seene as a crowe, but when he putteth on humane shape, at the commandement of the exorcist,

he stealeth woonderfullie out of the kings house, and carrieth it whether he is assigned, he destroieth cities, and hath great

despite unto dignities, he knoweth things present, past, and to come, and reconcileth freends and foes, he was of the order of

thrones, and governeth thirtie legions.

By the time of the Age of Ignorance, Raum was pushed into the enemy grimoires and represented as a monstrous entity taking the form

of a black crow, said also to steal treasures out of the houses of kings, which is a coy reference to his imperial endowment above.

He is said to know past, present, and future as a coy rewriting of his maintenance of life and to be a destroyer of cities in tandem

with his abilities to cause destruction in military terms.

The Holy Sigil of Khnum is shown below.

Bibliography:

1Theology and Physical Paternity, G.D. Hornblower

2The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, Richard H. Wilkinson

3Amon Ra, Temple of Zeus

4The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Ian Shaw

5Utterance 300, Pyramid Texts

6Column 11, Esna 298 The

Temple of Esna. An Evolving Translation: Esna III

7Famine Stela

8Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume III: The Late Period, Miriam Lichtheim

9Among the Priests of Elephantine Island: Elephantine Island Seen from Egyptian Sources, Mattias Müller, Die Welt des

Orients

10Dictionary of ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses, George Hart

11ELEPHANTINE, Sapienza: Università di Roma

12Esna, Jochen Hallof, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1

13A Family from Armant in Aswân and in Thebes, Labib Habachi Vol 51. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, pp. 123-136

14CHILD DEITIES/اآللھة على ھيئة الطفل, Dagmar Budde, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

15The Kellis Mammisi: A Painted Chapel from the Final Centuries of the Ancient Egyptian Religion, Olaf M. Kaper,

Institute for Area Studies,Leiden University

16An Egyptian Temple Reborn, Archaeology Magazine, Benjamin Leonard

17Two Graffiti at Sehēl from the Reign of Queen Hatshepsut, Labib Habachi, Vol. 16, No. 2, Journal of Near Eastern

Studies

18Pap. Berlin P. 23572, Texts and Scripts

from Elephantine Island in Egypt

19Pap. Berlin P. 13577, Texts and Scripts

from Elephantine Island in Egypt

20The Elephantine Papyri In English: Three Millennia of Cross Cultural Continuity and Change, Bezalel Porten

21Theology, Priests, and Worship in Ancient Egypt, Herman Te Velde

22"Four Faces on One Neck": The Tetracephalic Ram as an Iconographic Form in the Late New Kingdom, Matthew Treasure,

AUC Knowledge Fountain, American University in Cairo

23Thirteenth Olympian Ode, Pindar

241.9, Bibliotheca, Pseudo-Apollodorus

25Zodiaque de Dendéra, Louvre

26From Jewish Magic to Gnosticism, Attilio Mastrocinque

27The Wisdom of Thoth: Magical Texts in Ancient Mediterranean Civilisations, edited by Grażyna Bąkowska-Czerner,

Alessandro Roccati, Agata Świerzowska, Archaeopress

28Une Communauté Judéo-Araméenne à Éléphantine, en Egypte, aux vi et v siècles avant J.-C,Albin-Augustin Van Hoonacker

29Pseudomonarchia daemonum, Johann Weyer

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe